Farouk of Egypt

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

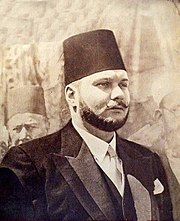

| Farouk I فاروق الأول | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Official portrait, 1946 | |||||

| King of Egypt and the Sudan[1] | |||||

| Reign | 28 April 1936 – 26 July 1952 | ||||

| Coronation | 29 July 1937[2] | ||||

| Predecessor | Fuad I | ||||

| Successor | Fuad II | ||||

| Regents | |||||

| Prime Ministers | |||||

| Head of the House of Alawiyya | |||||

| Reign | 18 June 1953 – 18 March 1965 | ||||

| Successor | Fuad II | ||||

| Born | 11 February 1920 Abdeen Palace, Cairo, Sultanate of Egypt | ||||

| Died | 18 March 1965 (aged 45) San Camillo Hospital, Rome, Italy | ||||

| Burial | Al-Rifa'i Mosque, Cairo, Egypt | ||||

| Spouses | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| House | Alawiyya | ||||

| Father | Fuad I of Egypt | ||||

| Mother | Nazli Sabri | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Farouk I (/fəˈruːk/; Arabic: فاروق الأول Fārūq al-Awwal; 11 February 1920 – 18 March 1965) was the tenth ruler of Egypt from the Muhammad Ali dynasty and the penultimate King of Egypt and the Sudan, succeeding his father, Fuad I, in 1936 and reigning until his overthrow in a military coup in 1952.

His full title was "His Majesty Farouk I, by the grace of God, King of Egypt and the Sudan". As king, Farouk was known for his extravagant playboy lifestyle. While initially popular, his reputation eroded due to the corruption and incompetence of his government. He was overthrown in the 1952 coup d'état and forced to abdicate in favour of his infant son, Ahmed Fuad, who succeeded him as Fuad II. Farouk died in exile in Italy in 1965.

His sister, Princess Fawzia bint Fuad, was the first wife and consort of the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[3]

Early life and education

[edit]

He was born as His Sultanic Highness Farouk bin Fuad, Hereditary Prince of Egypt and Sudan, on 11 February 1920 (Jumada al-Awwal 21, 1338 A.H.) at Abdeen Palace, Cairo, the eldest child of Sultan Fuad I (later King Fuad I) and his second wife, Nazli Sabri.[4][5] He had Albanian, Circassian, Turkish, French, Greek and Egyptian ancestry.[6][7][8][9] Farouk's first languages were Egyptian Arabic, Turkish and French (the languages of the Egyptian elite), and he always thought of himself as an Egyptian rather than as an Arab, having no interest in Arab nationalism except as a way of increasing Egypt's power in the Middle East.[10] Egypt at that time was quite rich, but its wealth was very maldistributed. The pashas, representing less than .5% of all landowners, owned a third of all cultivated land in the country.[11]

In addition to his sisters, Fawzia, Faiza, Faika and Fathia,[12] he had one half-sister from his father's previous marriage to Princess Shivakiar Khanum Effendi, Princess Fawkia. Fuad gave all of his children names starting with F after an Indian fortune-teller told him names starting with F would bring him good luck.[13] King Fuad kept tight control over his only son when he was growing up and Farouk was only allowed to see his mother once every day for an hour.[14] The prince grew up in the very closeted world of the royal palaces, and he never visited the Great Pyramids at Giza until he became king, despite the fact that only 19 kilometres (12 mi) separated the Abdeen Palace from the Pyramids.[15] Farouk had a very spoiled upbringing with the Sudanese servants when meeting him always getting down on their knees to first kiss the ground and then his hand.[16] Aside from his sisters, Farouk had no friends when growing up as Fuad would not allow any outsiders to meet him.[17]

Fuad, who did not speak Arabic, insisted that the crown prince learn Arabic so he could talk to his subjects.[15] Farouk became fluent in classical Arabic, the language of the Quran, and he always gave his speeches in classical Arabic.[18] As a child, Farouk showed a facility for languages, learning Arabic, English, French and Italian, which were the only subjects he excelled in.[15] The more honest of Farouk's tutors often wrote comments on his childhood essays such as "Improve your bad handwriting and pay attention to the cleanliness of your notebook" and "It is regrettable that you do not know the history of your ancestors".[15] The more sycophantic of his tutors wrote comments like "Excellent. A brilliant future awaits you in the world of literature" on an essay that began with the sentence "My father had a lot of ministers and I have a cat".[15] Farouk was known for his love of practical jokes, a trait that continued as an adult. For instance, he liked to free the quail that the game keepers had captured on the grounds of the Montaza Palace, and he once used an air gun to shoot out the windows at the Koubbeh Palace.[19] When Queen Marie of Romania visited the Koubbeh Palace to see Queen Nazli, Farouk asked her if she wanted to see his two horses; when she answered in the positive, Farouk had the horses brought into the royal harem, which greatly displeased the two queens as the animals defecated all over the floor.[20] Farouk's Swedish au pair, Gerda Sjöberg, wrote in her diary: "The truth doesn't exist in Egypt. Breaking promises is normal. Farouk is already perfect at this. He loves to lie. But it's amazing Farouk is as good as he, given his mother." [21] Knowing of his family's genetic predisposition to obesity, King Fuad kept Farouk on a strict diet, warning him that the male descendants of Muhammad Ali the Great tended to get obese very easily.[15]

Farouk's closest friend when growing up and later as an adult was the Italian electrician at the Abdeen Palace, Antonio Pulli, who became one of Egypt's most powerful men during his reign.[19][20][22] An attempt to enroll Farouk at Eton was thwarted when he failed the entrance exams.[18] Before his father's death, he was educated at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, England. The Italophile Fuad wanted to have Farouk educated at the Turin Military Academy, but the British High Commissioner Sir Miles Lampson vetoed this choice as growing Italian claims for the entire Mediterranean to be Mare Nostrum ("Our Sea") made it unacceptable for the Crown Prince to be educated in Italy.[18]

In October 1935, Farouk left Egypt to settle at Kenry House in the countryside of Surrey to attend the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich as an extramural student.[20] Farouk attended classes occasionally at "the Shop", as the academy was known, to prepare himself for the entrance exam.[23] Farouk stayed at Kenry House and twice a week was driven in a Rolls-Royce to the Royal Military Academy to attend classes, but still failed the entrance exam.[23] One of Farouk's tutors, General Aziz Ali al-Misri, complained to King Fuad that the principal problem with Farouk as a student was he never studied and expected the answers to be given to him when he wrote his exam.[24] Instead of studying, Farouk spent his time in London where he went shopping, attended football matches with the Prince of Wales, and visited restaurants and brothels.[25] Farouk's other tutor, the famous desert explorer, Olympic athlete and poet Ahmed Hassanein reported to King Fuad that Farouk was studying hard, but the inability of the crown prince to pass entrance exams supports General al-Misri's reports.[24] When King George V died in January 1936, Farouk represented Egypt at his funeral in Westminster Abbey.[26]

On 28 April 1936, King Fuad died of a heart attack and Farouk left England to return to Egypt as king.[26] Farouk's first act as king was to visit Buckingham Palace to accept the condolences of King Edward VIII, one of the few Englishmen whom Farouk liked, and then he went to Victoria Station to take a train to Dover and was seen off by the Foreign Secretary, Sir Anthony Eden.[27] At Dover, Farouk boarded a French ship, the Côte d'Azur, which took him to Calais.[27] After a stop in Paris to shop and visit the Elysee Palace, Farouk took the train to Marseilles, where he boarded an ocean liner, the Viceroy of India to take him to Alexandria, where he landed on 6 May 1936.[27] Upon landing in Alexandria, Farouk was greeted by huge crowds who shouted "Long live the king of the Nile!" and "Long live the king of Egypt and the Sudan!".[27] In 1936, Farouk was known by his subjects as al malik al mahbub ("the beloved king").[28] Besides inheriting the throne, Farouk also received all of the land that his father had acquired, which amounted to one seventh of all the arable land in Egypt.[29] As the Nile river valley has some of the most fertile and productive farmland in the entire world, this was a considerable asset.[30] Fuad left Farouk a fortune worth about US$100 million (a sum worth US$1,862,130,434 in 2020 dollars when adjusted for inflation) plus 30,000 hectares (75,000 acres) of land in the Nile river valley, five palaces, 200 cars and 2 yachts.[30] Farouk's biographer, William Stadiem, wrote:

no pharaoh, no Mameluke, no khedive ever began a reign with such unquestionable, enthusiastic goodwill as King Farouk. And none was as unprepared to rule. Here was a completely sheltered, virtually uneducated sixteen-year old, expected to fill the spats of his wily, politically astute father in a loaded tug-of-war between nationalism, imperialism, constitutionalism, and monarchy.[30]

Ascension

[edit]

Upon his coronation, the 16-year-old King Farouk made a public radio address to the nation, the first time a sovereign of Egypt had ever spoken directly to his people in such a way:

And if it is God's will to lay on my shoulders at such an early age the responsibility of kingship, I on my part appreciate the duties that will be mine, and I am prepared for all sacrifices in the cause of my duty. ... My noble people, I am proud of you and your loyalty and am confident in the future as I am in God. Let us work together. We shall succeed and be happy. Long live the Motherland!

As Farouk was extremely popular with the Egyptian people, it was decided by the Prime Minister, Aly Maher, that Farouk should not return to Britain as that would be unpopular, though one of the regents, Prince Muhammad Ali, had wanted Farouk to keep trying to be admitted on a full-time basis to the Royal Military Academy as a means of getting him out of the country.[31] Since under Egyptian law women could not inherit the throne, Farouk's cousin Prince Muhammad Ali was next in line to the throne. Prince Muhammad Ali was to spend the next 16 years scheming to depose Farouk so he could become king.[31] Egypt was in the process of negotiating a treaty that would reduce some of the British privileges in Egypt and make the country more independent in exchange for keeping Egypt in the British sphere of influence.[32] The ambitions of Benito Mussolini to dominate the Mediterranean led the Wafd—traditionally the anti-British party—to want to keep the British presence in Egypt, at least as long as Mussolini kept calling the Mediterranean Mare Nostrum.[33] For both the Wafd and the British, it was convenient to keep Farouk in Egypt so that when he signed the new Anglo-Egyptian treaty, it would not be seen as under duress as it would be if Farouk was living in Britain.[31] Sir Miles Lampson believed he together with assorted other British officials like the king's tutor, Edward Ford, could mould Farouk into an Anglophile.[34] Lampson's plans were derailed when it emerged that Farouk was more interested in duck-hunting than Ford's lectures and that the king had "bragged" he would "have the hell" with the British, saying they had humiliated him for long enough.[34]

The fact that Farouk had dismissed all of the British servants employed by his father, while keeping the Italian servants, suggested he had inherited Fuad's Italophilia.[35] Farouk especially resented Lampson's attempts to set himself up as a surrogate father, finding him impossibly patronising and rude, complaining that at one moment Lampson would address him as a king and the next moment would call him to his face a "naughty boy".[28] Lampson was 55 when Farouk acceded to the throne and he never learned how to treat the teenage Farouk as an equal.[28] The official was charmed by Egypt, which he regarded as a wondrous exotic land, but as his Arabic was not particularly good, his contacts with ordinary Egyptians were only on a superficial level.[36] Lampson was fluent in French and his social contracts were almost entirely with the Egyptian elite. Lampson wrote in his diary about the death of King Fuad: "Slippery customer though he was, he was an immense factor in the situation here and... we could always in the last resort get him to act in any particular line that we wished".[37] About Farouk, Lampson wrote he did not expect to have "a young immature King on our hands. I frankly don't know quite how that problem is going to be handled".[37]

Farouk was enamored of the glamorous royal lifestyle. Although he already had thousands of acres of land, dozens of palaces and hundreds of cars, the youthful king often traveled to Europe for grand shopping sprees, earning the ire of many of his subjects. It is said that he ate 600 oysters a week.[38] His personal vehicle was a red 1947 Bentley Mark VI, with coachwork by Figoni et Falaschi; he dictated that, other than the military jeeps which made up the rest of his entourage, no other cars were to be painted red.[39] In 1951, he bought the pear-shaped 94-carat Star of the East diamond and a fancy-coloured oval-cut diamond from jeweller Harry Winston.

He was most popular in his early years, and the nobility largely celebrated him. For example, during the accession of the young King Farouk, "the Abaza family had solicited palace authorities to permit the royal train to stop briefly in their village so that the king could partake of refreshments offered in a large, magnificently ornamented tent the family had erected in the train station."[40] The Chief Accountant to Farouk was Yadidya Israel, who was secretly working with the Free Officers movement that removed the King in 1952, as was the Abaza family's own Wagih Abaza, who later became governor of six governorates in post-Farouk Egypt.[41][42][43]

Farouk's accession initially was encouraging for the populace and nobility, due to his youth and Egyptian roots through his mother Nazli Sabri. Standing 6'0 tall and extremely handsome in his teenage years, Farouk was viewed as a sex symbol in his early years, making the cover of Time magazine as a leader to watch while Life magazine in article on him called the Abdeen Palace "possibly the most magnificent royal place in the world" and Farouk "the very model of a young Muslim gentleman".[44] However, the situation was not the same with some Egyptian politicians and elected government officials, with whom Farouk quarreled frequently, despite their loyalty in principle to his throne. There was also the issue of the British influence in the Egyptian government, which Farouk viewed with disdain. Farouk's accession had changed the dynamic of Egyptian politics from being a struggle of an unpopular king vs. the popular Wafd party as it was under his father to that of a popular Wafd vs. an even more popular king.[45] The Wafd Party, led by Nahas Pasha, had been the most popular party in Egypt since it had been founded in 1919, and the Wafd leaders felt threatened by Farouk's popularity with ordinary Egyptians.[45] Right from the start of Farouk's reign, the Wafd—who claimed to speak alone for Egypt's masses—saw Farouk as a threat and Nahas Pasha worked constantly to clip the king's power, confirming the prejudices that Farouk had inherited from his father against the Wafd.[46] When Nahas and the other Wafd leaders traveled to London to sign the Anglo-Egyptian treaty in August 1936, they stopped over in Switzerland to hold discussions with former Khedive Abbas II about how best to depose Farouk and put Abbas back on the throne. [31]

The dominant figure in the Wafd was Makram Ebeid, the man widely considered to be the most intelligent Egyptian politician of the interwar era.[47] Ebeid was a Coptic Christian, which made it unacceptable for him to be prime minister of Muslim majority Egypt, and so he exercised power via his protege Nahas, who was the official party leader.[47] Leaders in the Wafd like Ali Maher, opposed to Ebeid and Nahas, looked to Farouk as a rival source of patronage and power.[47] Both Ebeid and Nahas disliked Maher, regarding him as an intriguer and an opportunist, and found a further reason to dislike him even more when Maher became Farouk's favorite political adviser.[48] The nationalistic Wafd Party was the most powerful political machine in Egypt, and when the Wafd was in power, it tended to be very corrupt and nepotistic.[49] Those excluded from opportunities for corruption, like Maher Pasha, made much of the corruption, in particular the baleful influence of Nahas Pasha's dominating wife[who?] (who insisted on giving high government jobs to members of her family, no matter how unqualified they were).[49] Though the Wafd Party had been founded in 1919 as the anti-British party, the fact that Nahas Pasha championed the 1936 treaty as the best way of keeping Mussolini from conquering Egypt as he had done Ethiopia, paradoxically led Lampson to favor Nahas and the Wafd as the most pro-British party, in turn leading opponents of the Wafd to attack them for "selling out" by signing a treaty which allowed the British to keep their garrisons in Egypt.[50] As Farouk could not stand the overbearing Lampson, and saw the Wafd as his enemies, the king naturally aligned himself with the anti-Wafd factions and those who saw the treaty as a "sell out".[51] Lampson personally favored deposing Farouk and putting his cousin Prince Muhammad Ali on the throne in order to keep the Wafd in power, but feared that a coup would destroy the popular legitimacy of Nahas.[52]

Despite the regency council, Farouk was determined to exercise his royal prerogatives. When Farouk asked for a new railroad station to be built outside of the Montazah palace, the council refused under the grounds that station was only used twice a year by the royal family, when they arrived at the Montazah palace to escape the summer heat in Cairo and when they returned to Cairo in the fall.[53] Unwilling to take no for an answer, Farouk called out his servants and led them to demolish the station, forcing the regency council to approve building a new station.[54] To counterbalance the Wafd, Farouk from the time he arrived back in Egypt started to use Islam as a political weapon, always attending the Friday prayers at the local mosques, donating to Islamic charities, and courting the Muslim Brotherhood, the only group capable of rivaling the Wafd in terms of the ability to mobilize the masses.[28] Farouk was known in his early years as the "pious king" as unlike his predecessors he went out of his way to be seen as a devout Muslim.[28] The Egyptian historian Laila Morsy wrote that Nahas never really tried to reach an understanding with the Palace, and treated Farouk as an enemy from the start, seeing him as a threat to the Wafd.[46] The Wafd ran a powerful patronage machine in rural Egypt and the enthusiastic response of the fellaheen to the king as he threw gold coins at them during his tours of the countryside was viewed by Nahas as a major threat.[47] Nahas sought to prevent the king from "parading" himself before the masses, claiming that the king's royal tours cost the government too much money, and as the Wafd was a secularist party, charged that Farouk's overt religiosity violated the constitution.[46] However, the attacks by the secularist Wafd on Farouk for being too pious a Muslim estranged conservative Muslim opinion who rallied in defense of the "pious king".[55] As the Coptic Christian minority tended to vote as a bloc for the Wafd and many prominent Wafd leaders like Ebeid were Copts, the Wafd was widely seen as the "Coptic party".[47] The aggressive defense by Nahas of secularism as a core principle of Egyptian life and his attacks against the king as a danger for being a devout Muslim led to a backlash and the charge that secularism was merely a device for allowing the Coptic Christian minority to dominate Egypt at the expense of the Muslim Arab majority.[47]

Sir Edward Ford, who served as the king's tutor, described him as a relaxed, gregarious and easy-going teenager whose first act upon meeting him in Alexandria was to take him swimming in the Mediterranean.[56] However, Ford also described Farouk as incapable of learning and "totally incapable of concentration".[57] Whenever Ford began a lesson, Farouk would immediately find a way to end it by insisting that he take Ford out for a drive to see the Egyptian countryside.[58] In an interview in 1990, Ford described Farouk as: "He was half a private schoolboy of nine or ten and half a sophisticated young man of twenty-three, able to sit next to a great man like Lord Rutherford and impress him a great deal, usually by bluffing. He did have a very good eye, a royal eye. In England, he was able to spot the most valuable rare book in the Trinity College library in Cambridge. It may have been pure luck. But it impressed everyone. And he spoke wonderful English and Arabic".[58] In turn, Farouk explained to Ford why upper-class Egyptian men were still using the titles left over from the Ottoman Empire such as pasha, bey and effendi, which Ford learned that a pasha was equivalent to being an aristocrat, a bey was equivalent to a title of knighthood and an effendi to being an esquire.[54] Ford wrote in his notebook: "A pasha may perhaps be defined as a person who looks important, a bey thinks himself important, an effendi hopes to be important".[54] When Farouk went on his tour of Upper Egypt in January 1937, going down the Nile on the royal yacht Kassed el Kheir, Ford complained that Farouk never asked for a single lesson, as he was more interested in watching the latest films from Hollywood.[59] Despite the fact that Upper Egypt was the poorest region in Egypt, various mudirs (governors) and sheikhs held camel races, gymnastic events, stick boxing matches, banquets and concerts in honor of the king, which led Ford to write of a "record of unrivaled stardom, of which Greta Garbo might well be envious".[60]

On 29 June 1937, Farouk turned 17 under the Islamic lunar calendar, and since in the Islamic world a baby is considered to be one year old at the time of birth, by Muslim standards he was celebrating his 18th birthday.[61] As he was considered 18, he thus attained his majority, and the Regency Council, which had irked Farouk so much, was dissolved.[61] Farouk's coronation, held in Cairo, on 20 July 1937, outdid the coronation of George VI, which had just taken place that May, as Farouk held larger parades and fireworks displays than had taken place in London.[62] For his coronation, Farouk reduced the fares on the Nile steamers and at least two million fellaheen (Egyptian peasants) took advantage of the price cut to attend his coronation in Cairo.[61] Farouk's coronation speech implicitly criticized the land-owning Turco-Circassian elite that he himself was a part of, as Farouk declared: "The poor are not responsible for their poverty but rather the wealthy. Give to the poor what they merit without their asking. A king is a good king when the poor of the land have the right to live, when the sick have the right to be healed, when the timid have the right to be tranquil and when the ignorant have the right to learn".[63] Farouk's coronation speech, which was unexpectedly poetic, was written by his tutor, the poet Ahmed Hassanein, who felt that the king should present himself as the friend of the fellaheen to undercut the populist Wafd Party.[63] Further cementing Farouk's popularity was the announcement made on 24 August 1937, that he was engaged to Safinaz Zulficar, the daughter of an Alexandria judge.[64] Farouk's decision to marry a commoner instead of a member of the Turco-Circassian aristocracy increased his popularity with the Egyptian people.[64]

The marriage of the king and a commoner was presented to the world as matter of romantic love, but in fact the marriage had been arranged by Queen Nazli, who herself was a commoner and did not want her son to marry a princess from the Turco-Circassian elite who would outrank her.[64] Queen Nazli had chosen Zulficar as her daughter-in-law because she was 15 years old and thus presumably could be molded, and came from an upper-middle-class family like herself (Zulficar's mother was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Nazli) and was fluent in French, the language of Egypt's elite.[64] Zulficar's father refused to give permission for the marriage under the grounds that his daughter was 15 and too young to be married, and decided to take a vacation in Beirut.[65] Unwilling to take no for an answer, Farouk phoned the police chief of Alexandria, who arrested Judge Zulficar as he was boarding the ship for Beirut, and the judge was taken to the Montaza Palace.[65] At the Montaza palace, Farouk was waiting and bribed Judge Zulficar into granting permission for the marriage by making him into a pasha.[65] At Salfinaz Zulficar's 16th birthday party, Farouk arrived in his Alfa Romeo automobile to propose marriage, and at the same time renamed her Farida because he believed names that started with F were lucky.[65] (Safinaz is Persian for "pure rose" while Farida is Arabic for "the only one"; Farouk's decision to give his bride an Arabic name appealed to the masses).[65] Farouk gave Farida a cheque for a sum in Egyptian pounds equivalent to $50,000 US dollars as a wedding dowry and a diamond ring worth just as much for the engagement.[65] Outside of the Ras El Tin Palace, when the wedding was announced, 22 people were crushed to death and 140 badly injured when the crowd rushed forward to hear the news.[65]

In the fall of 1937, Farouk dismissed the Wafd government headed by Prime Minister Mostafa El-Nahas and replaced him as Prime Minister with Mohamed Mahmoud Pasha.[66] The immediate issue were Nahas's attempts to dismiss Farouk's chef de cabinet Ali Maher together with Farouk's Italian servants, but the more general issue was who would rule Egypt: the Crown or Parliament?[66] As a number of ministers in the new government were pro-Italian at the same time that Mussolini was increasing the number of Italian troops in Libya, Farouk's move was seen as pro-Italian and anti-British. Lampson delivered what he called a "little lecture" to Farouk, reporting to London: "It will be fatal if the boy [Farouk] comes to think he is invincible and can play any trick he likes. Personally I have always liked him and he certainly has a most remarkable intelligence and courage—one begins to fear almost too much of the latter".[66] At a meeting at the Abdeen Palace in December 1937, where Lampson declared that London was opposed to the Mahmoud government, Lampson reported: "I found him rather baffling to deal with—in extraordinary good humour and apparently taking the whole thing rather flippantly whist at times relapsing into a very 'kingly' attitude".[67] Farouk told Lampson that he didn't care if the Wafd had a majority in Parliament, as he was the king and he wanted a prime minister who would obey him, not Parliament.[67] Lampson ended the meeting by saying Quos deus vult perdere prius dementat ("Those God wishes to destroy, he first makes mad").[67]

On 20 January 1938, Farouk married Farida in a sumptuous public event with Cairo lit up by floodlights and colored lights on the public buildings while boats on the Nile had likewise had colored lights, making the river seem a ribbon of light at night.[68] Farida wore a wedding dress that Farouk had bought her, which was handmade in Paris and cost about $30,000 US dollars.[69] The royal wedding made Farouk even more popular with the Egyptian people, and he dissolved parliament for elections in April 1938 with the full prestige and wealth of the Crown being used to support parties opposed to the Wafd.[67] The prime minister, Nahas Pasha, used the familiar Wafd slogan "The king reigns; he does not rule", but the Wafd suffered a massive defeat in the election.[67] In 1938, Farouk was approached by the Iranian ambassador with a message from Reza Khan, the Shah of Iran, asking that his sister be married to Mohammad Reza, the Crown Prince of Iran.[70] When a group of Iranian emissaries arrived in Cairo bearing gifts from Reza Khan such as a "diamond necklace, diamond brooch, diamond earrings", Farouk was not impressed, taking the Iranian delegation on a tour of his five palaces to show them proper royal splendor and asked if there was anything comparable in Iran.[71] Nonetheless, Farouk agreed in a joint press communique issued with Reza Khan on 26 May 1938, that Princess Fawzia would marry Crown Prince Mohammad Reza, who first learned that he was now engaged to Fawzia when he read the press release.[71]

Farouk broke with Muslim tradition by taking Queen Farida everywhere with him, and letting her go unveiled.[72] On 17 November 1938, Farouk became a father when Farida gave birth to Princess Farial, a considerable disappointment as Farouk wanted a son, all the more because he knew his cousin, Prince Muhammad Ali, was scheming to take the throne.[73] In March 1939, Farouk sent the royal yacht Mahroussa to Iran to pick up the Crown Prince.[71] On 15 March 1939, Mohammad Reza married Fawzia in Cairo and afterwards Farouk took his brother-in-law on a tour of Egypt, showing him his five palaces, the Pyramids, Al-Azhar University and other sites in Egypt.[71] In April 1939, the German propaganda minister, Dr. Josef Goebbels, visited Cairo and received a warm welcome from the king.[74] The Danzig crisis which led to World War II later that year had already begun when Farouk met Goebbels, and the meeting caused Lampson much alarm, as he suspected the king was an Axis sympathizer.[74] In August 1939, Farouk appointed his favorite politician, Maher Pasha, prime minister.[75]

Reign

[edit]

World War II

[edit]Egypt remained neutral in World War II, but under heavy pressure from Lampson, Farouk broke diplomatic relations with Germany in September 1939.[76] On 7 April 1940, Queen Farida gave birth to a second daughter, Princess Fawzia, which greatly upset Farouk.[77] After Fawzia's birth, Farouk's marriage started to become strained as he wanted a son.[78] In Egypt, a son was much more valued than daughters for the kingdom's legacy; according to Egyptian law at the time a daughter could not inherit the throne, and Farouk was becoming widely viewed as lacking in masculinity due to the absence of a son.[79] Farouk consulted various doctors, who advised him to eat foods that were felt to increase sex drive, and Farouk became something of a bulimic, eating excessively and later becoming overweight.[79] Suspicions that Queen Farida was having an affair with aristocrat Wahid Yussri imposed strains on the marriage.[77]

Under the 1936 treaty, Britain had the right to defend Egypt from an invasion, which turned the Western Desert of Egypt into a battlefield when Italy declared war on Britain on 10 June 1940, and invaded Egypt.[80] Under the 1936 treaty, the Egyptians were obligated to assist the British with logistical services, but Maher frustrated this by appointing corrupt bureaucrats to positions such as presidency of the Egyptian state railroad who demanded baksheesh (bribe) in exchange for co-operating.[81] Owing to the strategic importance of Egypt, ultimately 2 million soldiers from Britain, Australia, India and New Zealand arrived in Egypt.[82] Lampson was against Egypt declaring war on the Axis powers despite the Italian invasion of Egypt as having Egypt as a belligerent would mean Egypt would have the right to attend the peace conference once the Allies had won the war, and as Lampson put it, the Egyptians would make demands that would be "embarrassing" for the British at such a peace conference.[83]

Farouk was greatly upset in 1940 when he learned that his mother, Queen Nazli, whom he viewed as a rather chaste figure, was having an affair with his former tutor, Prince Ahmed Hassanein, who as a desert explorer, poet, Olympic athlete and aviator, was one of the most famous Egyptians alive.[78] When Farouk caught Hassanein reading passages from the Koran to his mother in her bedroom, he pulled out a handgun and threatened to shoot them, saying "you are disgracing the memory of my father, and if I end it by killing one of you, then God will forgive me, for it is according to our holy law as you both know".[84] Distracting Farouk from thoughts of matricide was a meeting on 17 June 1940, with Lampson who demanded that Farouk dismiss Maher as prime minister and General al-Misri as chief of staff of the Egyptian Army, saying both were pro-Axis.[80] Lampson wrote to London: "I repeated I hoped that he realized we were in deadly earnest. He said he knew that full well, and cryptically, that so was he".[85]

On 28 June 1940, Farouk dismissed Maher Pasha as prime minister, but refused to appoint Nahas Pasha as prime minister as Lampson wanted, saying that Nahas was full of "Bolshevik schemes".[85] The new prime minister was Hassan Sabry, whom Lampson felt was acceptable, and despite his previous threats to kill him, Prince Hassanein was made chef de cabinet.[85] Prince Hassanein had been educated at Oxford University and unusually for an Egyptian, was an Anglophile, having fond memories of his time in England when he studied at Oxford.[85] Lampson had come to detest Farouk by this time, and his favorite advice to London was "the only thing to do is kick the boy out".[85] In November 1940, the Prime Minister Sabry died of a heart attack when delivering his opening speech to Parliament and was replaced with Hussein Serry Pasha.[86] Farouk felt very lonely as a king, not having any real friends, made worse by the very public feud between Queen Farida and Queen Nazli as the former hated the latter for her attempts to dominate her.[87] Farouk's best friend was Pulli, who was more of a "man Friday".[86] Maher had made contacts on behalf of the king with General al-Misri, on "sick leave" since June 1940; with a group of anti-British officers in the Egyptian Army, and Hassan el Banna, the Supreme Guide of the Muslim Brotherhood, to discuss a possible anti-British uprising when the Axis broke through the British lines.[88] Egypt together with the American South was one of the few places in the world suitable for growing cotton, a water-intensive and labor-intensive crop that was traditionally known as "white gold" owing to the high prices it fetched. World War II created a huge demand for cotton, and after the United States entered the war in late 1941, so many American men were called up for service with the armed forces that Egypt became the only source of cotton for the Allies. For those who owned farmland in Egypt on which cotton was grown, the Second World War was a time of prosperity as the high prices of cotton counteracted the effects of wartime inflation.[89]

The Italians had only advanced within 80 kilometres (50 mi) of Egypt before stopping at Sidi Barrani, and on 9 December 1940, the British launched an offensive that drove the Italians back into Libya.[90] In response, in January 1941, German forces were dispatched to the Mediterranean to assist the Italians and on 12 February 1941, the Afrika Korps under the command of Erwin Rommel arrived in Libya.[91] Starting on 31 March 1941, a Wehrmacht offensive drove the British out of Libya and into Egypt.[92] As 95% of Egyptians live in the Nile river valley, the fighting in the Western Desert only affected the Bedouin nomads who lived in the desert.[93] At the same time in 1941 that Rommel was inflicting a series of defeats on the British in the Western Desert, Farouk wrote to Adolf Hitler promising him that when the Wehrmacht entered the Nile river valley, he would bring Egypt into the war on the Axis side.[94] The American historian Gerhard Weinberg wrote that the fact that Farouk wanted to see his country occupied by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany was not a sign of great wisdom on his part, but rather because he never understood "that Axis rule of Egypt was likely to be far more oppressive than British".[93]

During the hardships of the Second World War, criticism was levelled at Farouk for his lavish lifestyle. His decision not to put out the lights at his palace in Alexandria when the city was blacked out because of German and Italian bombing was deemed particularly offensive by the Egyptian people. This was a large contrast to the British royal family back in England, who were well known to have an opposite reaction to the bombings near their home. Owing to the continuing British occupation of Egypt, many Egyptians, Farouk included, were positively disposed towards Germany and Italy, and despite the presence of British troops, Egypt remained officially neutral until the final year of the war. Consequently, Farouk's Italian servants were not interned, and there is an unconfirmed story that Farouk told British Ambassador Sir Miles Lampson (who had an Italian wife), "I'll get rid of my Italians when you get rid of yours". Many Italians in Egypt, mostly men, were interned in British concentration camps, such as the notorious camp Fayed, 40 kilometres (25 mi) outside of Cairo. Treatment of these prisoners in those camps was extreme and physically excessively harsh, many losing inordinate amounts of body weight and contracting typhus. In January 1942, when Farouk was away on vacation, Lampson pressured Serry Pasha into breaking diplomatic relations with Vichy France.[95] As the king was not consulted about the severing of ties with Vichy France, Farouk used this violation of the constitution as an excuse to dismiss Serry and announced he planned to appoint Maher as prime minister again.[96] Serry knew that his government was likely to be defeated on a motion of no confidence when Parliament opened on 3 February 1942, and in the meantime demonstrations by students at Cairo University and Al-Azhar University had broken out, calling for a German victory.[97]

Following a ministerial crisis in February 1942, the British government, through its ambassador in Egypt, Sir Miles Lampson, pressed Farouk to have a Wafd or Wafd-coalition government replace Hussein Sirri Pasha's government. Lampson had Sir Walter Monckton flown in from London to draft an abdication decree for Farouk to sign as Monckton had drafted the abdication decree for Edward VIII and it was agreed that Prince Muhammad Ali would become the new king.[98] Lampson wanted to depose Farouk, but General Robert Stone and Oliver Lyttleton both argued that if Farouk agreed to appoint Nahas Pasha prime minister that the public reaction to "throwing the boy out for giving us at 9 p.m. the answer which we should have welcomed at 6 p.m." would be highly negative.[99] Reluctantly, Lampson agreed that Farouk could stay if he agreed to make Nahas prime minister.[99] Farouk asked his military how long the Egyptian Army could hold Cairo against the British and was told at most they could for two hours.[100] On the night of 4 February 1942, soldiers surrounded Abdeen Palace in Cairo and Lampson presented Farouk with an ultimatum. While a battalion of infantry took up their positions around the palace with the roar of tanks could be heard in the distance, Lampson arrived at the Abdeen Palace in his Rolls-Royce together with General Stone.[99] As the doors to Abdeen Palace were locked, one of the officers present used his revolver to shoot open the door and Lampson stormed in, demanding to see the king at once.[99] Farouk initially started to sign the abdication degree that Lampson had placed on his desk, but Prince Hassanein, who was present as a sort of mediator, intervened and spoke to Farouk in Turkish, a language which he knew that Lampson did not speak.[101] Unknown to Lampson, three of Farouk's Albanian bodyguards were hiding behind the curtains in his study with orders to shoot the ambassador if he should touch Farouk.[102] Prince Hassanein's intervention had its effect, and Farouk turned to Lampson to say he was giving in.[101] Farouk capitulated, and Nahhas formed a government shortly thereafter. However, the humiliation meted out to Farouk, and the actions of the Wafd in co-operating with the British and taking power, lost support for both the British and the Wafd among both civilians and, more importantly, the Egyptian military. At the time, the incident caused the Egyptian people to rally around their king, on 11 February 1942 (his birthday by Western standards), he received was loudly cheered by the crowd on Abdeen Square.[100] General Stone wrote Farouk a letter of apology for the incident.[103] Air Marshal William Sholto Douglas wrote that Lampson had made a huge error in "treating King Farouk as if he were nothing but a naughty and rather silly boy... Farouk was naughty and he was still very young... but to my mind, and taking a hard-headed view, he was also the King of Egypt".[104]

After the humiliation of the Abdeen Palace incident, Farouk lost interest in politics for the moment, and he abandoned himself to a lifestyle of hedonism as he became obsessed with "collecting" women by sleeping with them, having his closest friend, the Italian valet Antonio Pulli, bring in fair-skinned women from the dance halls and brothels of Cairo and Alexandria to his palaces for sex.[105] Despite his great wealth, Farouk was a kleptomaniac who always took something valuable such as a painting or a piano from whatever member of the Egyptian elite he stayed with, as no one could say no to the king and if he indicated he wanted something, his subjects had to give it to him.[106][107][108] When one of the daughters of the Ades family, one of the richest Jewish families in Egypt, rebuffed Farouk's advances, he arrived unannounced at the Ades family's estate on an island in the Nile with Pulli telling the Adeses that the king had come to hunt the gazelles.[108] Rather than have the kleptomaniac Farouk stay at their estate and wipe out the gazelles on their island, the Adeses agreed that their 16-year-old daughter would go to the Abdeen palace to be courted by the king.[103]

In April 1942, at a luncheon with Lampson and King George II of Greece, Farouk refused to speak to Lampson and told George that he would be wasting his time meeting the Wafd ministers as they were all ces canailles ("these scoundrels").[109] On 2 July 1942, Lampson visited the Abdeen Palace to tell Farouk that there was a real possibility of Axis forces taking Cairo and suggested that the king should flee to Khartoum if the Afrika Corps took Cairo.[109] Farouk who had no intention of decamping to Khartoum simply walked out of the room.[110] After the Battle of El Alamein, the Axis forces were driven out of Egypt and back into Libya, which caused Farouk to change his views over to a markedly pro-British direction.[111] Air Marshal Douglas, one of the few British people whom Farouk was friends with, gave him the uniform of a RAF officer, which became the king's favorite uniform.[112]

Farouk had something of a mania for collecting things ranging from Coca-Cola bottles to European art to ancient Egyptian antiques.[113] Farouk became addicted to eating and drinking soft-drinks, ordering his French chefs at the Abdeen palace to cook enormous meals of the finest French food, which he devoured and which caused him to become obese.[114] Farouk came to be known as "the king of the night" owing to the amount of time he spent in the exclusive Auberge des Pyramides nightclub in Cairo, where he spent his time socializing, smoking cigars and drinking orangeade.[115] Farouk also indulged in much childish behavior at the Auberge des Pyramides like throwing bread balls at the other patrons.[115] Farouks's grandfather, Ismail the Magnificent, had rebuilt Cairo in the style of Paris and during Farouk's reign, Cairo was considered to be a glamorous city, the most Westernized and wealthy city in the Middle East.[116] As a result, various celebrities from the West were constantly passing through Cairo and were invited to socialize with the king.[117]

Farouk also met various Allied leaders. South African Prime Minister Jan Christian Smuts called Farouk "surprisingly intelligent".[118] U.S. Senator Richard Russell Jr., who represented Georgia, a cotton-growing state, found he had much in common with Farouk and stated he was "an attractive, clear-eyed young man ... very much on the job ... well above the ordinary run of rulers".[118] The American financier and diplomat Winthrop W. Aldrich discovered that Farouk was very informed about the workings of the international gold market, saying the king had a sharp eye for business.[118] Air Marshal Douglas wrote "I began to genuinely like Farouk. There was no indication then there was anything that was vicious about him, although at times his flippancy became annoying. Another failing of his was that he appeared to be almost fanatically keen on acquiring great wealth ... he revealed all too clearly his shortsightedness in stating openly that one of his main interests in life was to increase that fortune. This led him into currying favor with the rich people in Egypt, as they did with him, at the expense of the common people, in whom he had little or no interest".[119] Douglas concluded that the king was "an intelligent young man ... he was by no means the fool that he appeared to be through the stupid way in which he quite often behaved in public".[120] However, a meeting with the British prime minister Winston Churchill in August 1942 when Farouk stole his watch did not make the best impression; though Farouk later returned the watch, presenting his theft of Churchill's watch as merely a practical joke, saying he knew "the English had a great sense of humor".[121] Farouk had pardoned a thief in exchange for teaching him how to be a pickpocket, a skill that Farouk used on Churchill, much to the latter's chagrin.[122]

In the time honored fashion, the Wafd government headed by Nahas proved to be an extremely corrupt and Nahas is widely considered to be one of the most corrupt Egyptian prime ministers of all time.[123] Nahas fell out with his patron, Makram Ebeid, and expelled him from the Wafd at the instigation of his wife.[89] Ebeid retaliated with The Black Book, a detailed expose published in the spring of 1943 listing 108 cases of major corruption involving Nahas and his wife.[89] On 29 March 1943, Ebeid visited the Abdeen Palace to present Farouk with a copy of The Black Book and asked that he dismiss Nahas for corruption.[124] Farouk attempted to use the furor caused by The Black Book as an excuse to dismiss the extremely unpopular Nahas, who had become Egypt's most hated man, but Lampson warned him via Prince Hassanein that he would be deposed if he dismissed his prime minister.[125] Lampson in a dispatch to Sir Anthony Eden, who was once again Foreign Secretary, argued that Egypt needed political calm and to allow Farouk to dismiss Nahas would cause chaos as the latter would start "ranting" against the British.[126] General Stone recommended that Lampson not be allowed to depose Farouk under the grounds that such a step was likely to cause anti-British rioting in Egypt which would require putting down, which Stone was opposed to on public relations grounds.[126] At the same time, Farouk, notwithstanding his own frequent unfaithfulness, had become enraged when he learned that Queen Farida was having an affair with the British painter, Simon Elwes, who had to flee Egypt to escape.[127] Lampson taunted Farouk when he learned that Queen Farida was pregnant again, saying he hoped she was bearing a son and that the boy was Farouk's.[127]

One of Farouk's mistresses, Irene Guinle, who was his "official mistress" in the years 1941–1943, described him as something of an immature "man-child" having no interest in politics and given to childish behavior like making bread balls at restaurants "to flip at the fancy people coming in and watch how they'd act when he hit the mark. How he roared with that laugh".[128] Guinle in an interview stated: "Farouk never wrote a letter, never read a paper, never listened to music. His idea of culture was movies. He never even played cards until I made the mistake of buying him a 'shoe' and teaching him how to play chemin de fer. He got hooked on that. Farouk was an insomniac. He had three telephones by his bed, which he would use to ring up his so-called friends at three in the morning and invite them to come over to his palace to play cards. No one could refuse the king".[129]

The British novelist Barbara Skelton replaced Guinle as the "official mistress" in 1943. Skelton called Farouk very immature and "a complete philistine", saying: "He was very adolescent. He didn't have the stuff to be a great king, he was too childish. But he never lost his temper, he was incredibly sweet, with a good sense of humor".[130]

In November 1943, Farouk went driving with Pulli in his red Cadillac to Ismalia to see a yacht he just purchased when he was involved in an automobile incident when his attempt to bypass a British Army truck by speeding caused him to hit another car head-on.[131] An attempt to place Farouk on a stretcher failed when the grossly overweight king turned out to be too heavy, causing the stretcher to break under his weight.[131] Farouk had suffered two broken ribs as a result of the car accident, but he liked being in a British Army hospital so much, flirting with the nurses, that he pretended to be injured far longer than what he really was.[132] As a result, Farouk missed the Cairo Conference when the U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek all arrived in Cairo to discuss war plans against Japan for 1944, though he appeared to have no regrets, preferring to spend his time flirting with the nurses and buying them gifts that were worth more than their annual salaries.[133] On 15 December 1943, Farouk was finally forced to end his convalescence when Farida gave birth to another daughter, Princess Fadia, which disappointed him, and caused him to lash out in anger against her for only giving him daughters.[133] Reflecting a continuing interest in the Balkans, the region where his family came from, Farouk by 1943 hosted King Zog I of Albania, King Peter II of Yugoslavia and King George II of Greece, telling all three kings that he wanted Egypt to play a role in the Balkans after the war, as he was proud of his Albanian ancestry.[133]

In late 1943, Farouk started a policy giving support to student and working men's association and in early 1944 paid a visit to Upper Egypt, when he donated money to victims of the malaria epidemic.[134] In April 1944, Farouk attempted to sack Nahas as prime minister over the latter's response to the malaria epidemic in Upper Egypt. [135] Reflecting the importance of controlling patronage in Egypt, Nahas Pasha had gone on a separate relief tour of Upper Egypt apart from the king and founded a relief organization, the Nahas Institute, in his own name instead of the king as was normal to treat the thousands sickened with malaria.[135] Farouk told Lampson that "there could not be two kings in Egypt" and the "semi-royal" nature of Nahas's tour of Upper Egypt was an insult to him.[136] Farouk attempted to soften the blow by announcing the new prime minister would be the well known Anglophile Prince Hassanein, but Lampson refused to accept him.[135] Lampson attempted to have Farouk deposed again, sending off a telegram to Churchill advising him to take "direct control" of Egypt.[135] Lampson once again threatened Farouk, who remained flippant and dismissive.[137] When Prince Hassanein tried to persuade Lampson to accept the dismissal of the deeply corrupt Wafd government as an improvement, the ambassador was unmoved, leading the normally Anglophile Hassanein to say the Egyptians were getting tired of British influence in their internal affairs.[138] By 1944, the withdrawal of much the British garrison in Egypt together with the view that to depose Farouk would make a nationalist martyr led to much of the British Foreign Office feeling that Lampson's constant plans to replace the king would do more harm than good.[139] Lord Moyne, the junior British foreign minister in charge of Middle Eastern affairs, told Lampson that his plans to depose Farouk in 1944 would damage Britain's moral position in the world and force the British to send more troops to Egypt to put down the expected riots when the main concern was the Italian theater of operations.[140] General Bernard Paget rejected Lampson's plans to depose Farouk as the Egyptian Army was loyal to him, and to depose the king would mean going to war against Egypt, which Paget called an unnecessary distraction.[140]

The day before Farouk was tentatively due to be deposed, Prince Hassanein arrived at the British Embassy with a letter for Lampson saying: "I am commanded by His Majesty to inform Your Excellency that he has decided to leave the present Government in Office for the time being".[141] As Nahas became unpopular, he sought to embrace Arab nationalism to rally support, having Egypt join the Arab League in October 1944 and speaking more and more about "the Palestine question".[142] In October 1944, when Lampson went away for a vacation in South Africa, Farouk finally dismissed Nahas as prime minister on 8 October 1944, and replaced him with Ahmed Maher, the brother of Ali Maher.[143] The dismissal of Nahas was seen by Lampson as a personal defeat, who complained in his diary that he would never have a politician "in our pocket" like him again, and was seen as a decisive turning point when Farouk had finally outwitted Lampson.[144] But at the same time, Lampson admitted that Nahas by his corruption had become a liability, and that Britain could not continue to support a corrupt government in the long run, as the British people would not tolerate going to war with Egypt to keep someone like Nahas in office.[145]

On 6 November 1944, Lord Moyne was assassinated in Cairo by two members of the extreme right-wing Zionist group, Lehi, better known as the Stern Gang.[146] The two assassins, Eliyahu Bet-Zuri and Eliyahu Hakim, gunned down Lord Moyne and his chauffeur, but were then captured by the Cairo police.[146] Afterwards, Bet-Zuri and Hakim were tried and sentenced to death by an Egyptian court.[147] Farouk came under strong pressure from American Zionist groups to pardon the two assassins while Lampson pressured him not to pardon the assassins.[147] For a time, Farouk escaped the matter by sailing on the royal yacht Mahroussa to Saudi Arabia to go on the haji to Mecca and meet King Ibn Saud.[148] In March 1945, the assassins of Lord Moyne were hanged, and for the first time, Farouk was accused in the United States of being anti-Semitic.[149]

Farouk declared war on the Axis Powers, long after the fighting in Egypt's Western Desert had ceased.[150] On 13 February 1945, Farouk met President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the United States on abroad the cruiser USS Quincy, anchored in the Great Bitter Lake.[151] Farouk seemed confused by the purpose of the meeting with Roosevelt, talking much about how after the war he hoped more American tourists would visit Egypt and Egyptian-American trade would increase.[151] Though the meeting consisted mostly of pleasantries, Roosevelt did give Farouk the gift of a Douglas C-47 plane, to add to his airplane collection.[152] After meeting Roosevelt, the king met Churchill who according to Lampson:

told Farouk that he should take a definite line in regard to the improvement of the social conditions in Egypt. He ventured to affirm that nowhere in the world were the conditions of extreme wealth and extreme poverty so glaring. What an opportunity for a young Sovereign to come forward and champion the interests and living conditions of his people. Why not take from the rich Pashas some of their superabundant wealth and devote it to the improvement of the living conditions of the fellaheen?.[153]

Farouk was more interested in learning if Egypt would be allowed to join the new United Nations and learned from Churchill that only nations that were at war with the Axis powers would be allowed to join the United Nations, which would replace the League of Nations after the war.[153]

In 1919, it had been a great humiliation for the Egyptians that Egypt had been excluded from the Paris Peace Conference that led to the Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations, causing the revolution of 1919.[154] Farouk was determined that this time that Egypt would be a founding member of the United Nations, which would show the world that the country was ending British influence in Egyptian affairs.[154] On 24 February 1945, Prime Minister Maher had the Chamber of Deputies issue declarations of war against Germany and Japan, and as he was leaving the Chamber, he was assassinated by Mahmoud Isawi, a member of the pro-Axis Young Egypt Society.[154] Isawi was shaking Maher's hand and then pulled out his handgun, shooting the prime minister three times while screaming that he had betrayed Egypt by declaring war on Germany and Japan.[154] When Lampson arrived at the Koubbeh Palace to see Farouk, he wrote he was shocked instead to see instead "it was the wicked Aly Maher who was receiving condolences".[155] As a result, Egypt attended the peace conference in San Francisco in April 1945 that founded the United Nations.[154]

The new prime minister, Mahmoud El Nokrashy Pasha, demanded that the British finally keep the terms of the 1936 treaty by pulling out of the Nile river valley while university students rioted in Cairo demanding the British leave Egypt altogether.[155] Lampson by 1945 was widely seen in Whitehall as a man with an unrealistic view of Anglo-Egyptian relations and only Lampson's friendship with Churchill kept him on as an ambassador in Cairo.[156] The new Labour government that came into office in July 1945 wanted a new relationship with Egypt, and Farouk let it be known he wanted a new British ambassador.[156] The new Labour Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, a man of working-class origins, found the aristocratic Lampson to be a snob, and moreover Lampson's vehement disapproval of the Labour government's policy towards India further isolated him.[157] For all these reasons, Bevin was well disposed to Farouk's entreaties to replace Lampson.[158] Farouk had vaguely promised to carry out social reforms, a major concern in London as the wartime inflation had led to increases in support for the Egyptian Communist Party on the left and the Muslim Brotherhood on the right, and was willing to negotiate a new relationship with Britain.[159] Moreover, once the war had ended, the Wafd had returned to its traditional anti-British political position, which led Whitehall to conclude that Farouk was London's best hope of keeping Egypt in the British sphere of influence.[160] The Egyptian ambassador in London passed on messages from Farouk blaming Lampson all the problems in Anglo-Egyptian relations, and stated that Farouk would be willing to return to his father's policies of opposing the Wafd and of seeking British "moral support" after the war.[161]

Decline

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Egypt ended the Second World War as the richest country in the Middle East, owing largely to the high prices of cotton.[11] In 1945 in a reversal of the usual roles, Egypt was a creditor nation to the United Kingdom, with the British government owing Egypt £400 million.[11] The stark income disparities of Egyptian society meant the wealth of Egypt was very unequally distributed with the kingdom having 500 millionaires while the fellaheen lived in extreme poverty.[11] In 1945, a medical study showed that 80% of Egyptians suffered from bilharzia and ophthalmia, both diseases that were easily preventable and treatable.[11] The authors of the study noted both bilharzia and ophthalmia were spread by waterborne parasitic worms, and the prevalence of both diseases could easily be eliminated in Egypt by providing people with safe sources of drinking water. The bumbling response of the Egyptian authorities to the cholera epidemic in 1947 that killed 80,000 people was an additional cause of criticism as cholera is caused by drinking water contaminated with feces, and the entire epidemic could have been avoided if only ordinary Egyptians had sources of clean drinking water.[11] King Farouk had traditionally posed as the friend of the poor, but by 1945 such gestures that the king liked to engage in such as throwing gold coins at the fellaheen or dropping ping-pong balls from his plane that could be redeemed for candy were no longer felt to be sufficient.[11] Increasingly, demands were being made that the king should engage in social reforms instead of theatrical gestures like handing out gold coins during royal visits, and as Farouk was unwilling to consider land reform or improving the water sanitation, his popularity began to decline.[11] Farouk's social life also started to damage his image. The American journalist Norbert Schiller wrote "Farouk was seen frequently womanizing at the hottest night spots in Cairo and Alexandria. In Egypt, the king's gallivanting was put under wraps by the palace censorship office, but abroad pictures of a fat balding king surrounded by Europe's social elite were splashed across the world's tabloids."[162] Farouk's only act of self-restraint was that he refused to drink alcohol as however much his lifestyle departed from the one recommended by the Koran, he could not bring himself to break the Muslim prohibition on alcohol.[11] Farouk's chief advisers in ruling Egypt starting in 1945 were his "kitchen cabinet" consisting of his right-hand man, Antonio Pulli together with the king's Lebanese press secretary Karim Thabet; Elias Andraous, an ethnic Greek from Alexandria whom Farouk valued for his business skills; and Edmond Galhan, a Lebanese arms dealer whose official title was "general purveyor to the Royal Palaces", but whose real job was to engage in black market activities for the king.[163] Prince Hassanein warned Farouk against his "kitchen cabinet", saying all of them were greedy, unscrupulous men who abused the king's trust to enrich themselves, but Farouk disregarded his advice.[164] In February 1946, Prince Hassanein was killed in an automobile accident, and a secret marriage contract between him and Queen Nazli was found that was dated 1937, which infuriated Farouk.[165] After much lobbying on the part of Farouk, the new Labour government in London decided to replace Lampson with Sir Ronald Campbell as the British ambassador in Cairo, and on 9 March 1946, Lampson left Cairo, much to the king's glee.[158] In May 1946, Farouk granted asylum to former king of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, who had abdicated on 9 May 1946.[166] Farouk was repaying a family debt as Victor Emmanuel's father, King Umberto I, had granted asylum to Farouk's grandfather, Ismail the Magnificent, in 1879, but as Victor Emmanuel had supported the Fascist regime, his arrival in Egypt did much damage to Farouk's image.[166] In June 1946, Farouk granted asylum to Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, who escaped from France where he was being held on charges of being a war criminal, arriving in Egypt on a forged passport.[167] Farouk did not care that al-Husseini was urgently wanted in Yugoslavia on charges of being a Nazi war criminal for his role in organizing the massacres of Bosnian Serbs and Jews.[168] Farouk wanted the British to keep the 1936 agreement by pulling their troops out of Cairo and Alexandria, and felt having notoriously Anglophobic rabble-rousing Grand Mufti in Egypt would be a useful way of threatening them.[166] However, the way that Farouk addressed al-Hussenini as the "king of Jerusalem" appeared to suggest that he envisioned the Grand Mufti as the future leader of a Palestinian state.[169] Starting in June 1946, the British did finally pull out of the Nile river valley and henceforward the only place the British Army were stationed at in Egypt was at the gigantic base around the Suez Canal.[170] In August 1946, the British pulled out of the Citadel in Cairo.[157] By September 1946, the British pull-out from the Nile valley was complete.[158] Farouk continued to press the British to leave Egypt altogether, but the question of who would control the Sudan led to the collapse of the talks in December 1946.[170] Farouk considered the Sudan to be part of Egypt, and wanted the Anglo-Egyptian condominium over the Sudan to end at the same time that the British would pull out of Egypt, which the British were unwilling to accept.[170]

Having the charismatic al-Husseini in Egypt had the effect of focusing attention on the Palestine issue, a matter which most Egyptians had previously ignored, all the more so when al-Husseini made an alliance with Hassan al-Banna, the Supreme Guide of the fundamentalist Muslim Brotherhood, which was rapidly becoming the most powerful mass movement in Egypt with over a million members.[171] Farouk himself welcomed the Grand Mufti to royal receptions, and his speeches calling for jihad against Zionism did much to put the "Palestine Question" on the public agenda.[172] Farouk himself was not personally anti-Semitic, having a Jewish mistress, the singer Lilianne Cohen, better known by her stage name Camelia, but given increasing discontent with the very stark income inequalities in Egypt, Farouk felt taking a militantly anti-Zionist line was the best way of distracting public attention.[173] At the Royal Automobile Club in Cairo, Farouk engaged in all night gambling sessions with rich Egyptian Jews despite his professed anti-Zionism and often joked: "Bring me my Zionist enemies so I can take their money!"[174] In December 1947, a demonstration organized by the Muslim Brotherhood in Cairo calling for Egyptian intervention in Palestine drew 100,000 people.[175] In November 1947, when Britain announced it was terminating the Palestine Mandate in May 1948, a civil war erupted between the Jewish and Arab populations of Palestine, and the fighting was very extensively covered by the Egyptian media.[175] The stories about atrocities, both real and imagined, against the Palestinians, served to greatly agitate the Egyptian people.[175] Furthermore, there was a widespread belief in Egypt that once the British left Palestine and the Zionists proclaimed a new state to be called Israel, that the resulting war would be an easy "march on Jerusalem" lasting only a few days.[175] In December 1947, a summit of the leaders of the Arab League was held in Cairo to discuss what to do when the Mandate of Palestine came to an end in May 1948.[176] King Abdullah I of Jordan wanted all of Palestine for himself and dismissed Farouk as a pseudo-Arab who should not even be attending the summit, saying with reference to Farouk's Albanian ancestry: "You do not make a gentleman out of a Balkan farmer's son simply by making him a king".[176]

Reflecting the influence of King Ibn' Saud of Saudi Arabia who spoke in the same way, Farouk often described Zionism as a ploy by the Soviet Union to take over the Middle East, calling the Zionists Jewish "communists" from Eastern Europe who were working on Moscow's instructions to "wreck" the traditional order in the Middle East.[172] Both Farouk and Ibn' Saud detested Abdullah, and both preferred that a Palestinian state headed by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem be created rather than see Palestine annexed to Jordan or becoming a Jewish state.[172] Farouk did not bother to tell the prime minister Mahmoud El Nokrashy Pasha about his decision for war with Israel, who only learned of his decision a few days before the war was due to start on 15 May 1948, from the Defense Minister and Chief of the General Staff.[177] Farouk was so convinced that the war would be a victorious "march on Jerusalem" that he had already started planning the victory parade in Cairo before the war started.[177] Farouk was described as "like some boy playing with so many lead soldiers" as he involved himself deeply in the military planning, personally deciding where his army would march when it invaded Palestine.[177] As late as 13 May 1948, Norakshy Pasha was assuring foreign diplomats that Egypt would not attack Israel when it was expected to be proclaimed on 15 May, and Egypt's intervention in the war took most observers by surprise.[178] In the diplomacy in the run-up to the war, Egypt was generally seen as a moderate state with Egyptian diplomats repeatedly saying that their country was opposed to a military solution to the "Palestine Question".[179] Nokrashy in 1947 asked in private if it was possible for the United States to take over the Palestine Mandate when the British left, saying he did not want a war.[180]

In May 1948, the prime minister Mahmoud El Nokrashy Pasha advised against going to war with Israel, saying the Egyptian Army was not ready for war.[181] However, King Farouk overruled him, as he feared the growing popularity of the Muslim Brotherhood, which was clamoring for war with Israel.[181] Farouk declared that Egypt would fight Israel as otherwise he feared the Muslim Brotherhood would overthrow him.[181] The war with Israel ended in disaster with the Egyptian Army fighting very poorly and Edmond Galhan of the king's "kitchen cabinet" making a fortune by selling the Egyptian Army defective Italian Army rifles left over from World War II, a matter which greatly angered many Egyptian officers.[181] Though the defective rifles were not the only reason why Egypt was defeated, many Egyptians came to be fixated on the issue, believing if it were not for Galhan, then Egypt would have been victorious.[181] It was after being defeated by Israel that the Abdeen Palace incident of 1942 started to be viewed in Egypt as an abject, contemptible surrender, which showed Farouk's cowardice and general lack of leadership.[182]

The Muslim Brotherhood, which had been so hawkish on war with Israel, turned its fury against the government in reaction to the defeats inflicted by Israel and in October 1948, a Brother killed the Cairo police chief, followed up by the governor of the Cairo province.[183] On 17 November 1948, Farouk divorced the very popular Queen Farida which, coming in middle of the losing war with Israel, was a profound shock to the Egyptian people.[184] On the same day, the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlevi, divorced Princess Fawzia.[185] Farouk and Mohammad Reza had planned to divorce their wives on the same day to distract the media from giving too much attention to either of their stories.[186] On 28 December 1948, Prime Minister Nokrashy Pasha was assassinated by a Brother disguised as a policeman.[183] In January 1949, Egypt signed an armistice with Israel with the only gain being the Gaza Strip.[184] In February 1949, the Supreme Guide of the Brotherhood, al-Banna, who called for Farouk's overthrow in response to the armistice with Israel, was shot by a Cairo policeman, and was taken to the hospital, where the police prevented him from receiving blood transfusions, causing his death later the same day.[183] Shortly afterward, al-Hussenini left Egypt for Lebanon.[183]

In the meantime, Farouk spent his nights at the Auberge des Pyramides nightclub with Cohen or his latest mistress, the French singer Annie Berrier.[187] At the same time, Farouk was engaged in a relationship with the American model Patricia "Honeychilde" Wilder, who stated in an interview that of all her lovers, he was the one who had the best sense of humour and made her laugh the most.[188] In September 1949, when Jefferson Caffery arrived in Cairo as the new U.S. ambassador and met Farouk for the first time, the king told Caffery (who came from Louisiana) that just as the South had its blacks good only for picking cotton, so too did Egypt have its fellaheen likewise only good for picking cotton.[189] Karim Thabet of the "kitchen cabinet", a man whom Caffery called a "jackal", convinced Farouk that the best way of renewing his popularity was to marry again, saying the Egyptian people loved royal weddings and to marry a commoner again would show his populist side.[190] Caffery reported that the king had listed his requirements for his new bride that she be of the grande bourgeoise class, be at least 16 years old, be an only child, and be of Egyptian descent only.[190] Thabet selected Narriman Sadek to be the new bride of the king, notwithstanding she was already engaged to Zaki Hashem, a PhD candidate in economics at Harvard University who was working in New York as a United Nations economist.[191] After Farouk had made Sadek's father a bey, he broke off her engagement to Hashem who complained to the American press that the king had stolen his fiancée and broken his heart.[192] After Farouk announced his engagement to Sadek, he sent her off to Rome to be taught how to be a proper cultured lady to make her fit to be a queen.[193] In January 1950, in a volte-face that stunned observers of Egyptian politics, Thabet arranged an alliance between the king and Nahas Pasha.[194] Caffery reported to Washington:

The proposal was that the King would receive Nahas in private audience prior to summoning a Wafd government and that if the King were not satisfied by his conversation with Nahas, Nahas gave his word of honor that he would retire from the leadership of the Wafd Party ... The King agreed to this proposal and was completely captivated by Nahas, who tactfully started the interview by swearing that his one desire in life was to kiss the King's hand and to remain always worthy in His Majesty's opinion of being allowed to repeat the performance. At this point Nahas went on his knees before the King who according to Thabet was so charmed that he assisted him to his feet with the words, "Rise, Mr. Prime Minister".[194]

Caffery reported in his cable to Washington that he was appalled that Nahas, whom Caffery called the stupidest and most corrupt politician in Egypt, was now prime minister.[195] Caffery stated that Nahas was unqualified to be prime minister because of his "completely total ignorance of the facts of life as they apply to the situation today", giving the example:

Most observers are willing to concede that Nahas knows of the existence of Korea, but I have found no one who would be willing to seriously contend that he is aware of the fact that Korea borders on Red China. His ignorance is as colossal as it is appalling ... At the time of my interview with Nahas he was totally unconscious of the subject which I was discussing. The only ray of light which penetrated was the fact that I wanted something from him. This prompted the street politician's response of "aidez-nous et nous vous aiderons".[195]

Caffery called Nahas a venal "street politician" whose only platform was the "tried and true formula of 'Evacuation and Unity of the Nile Valley'" and stated the only positive aspect of him as prime minister was that "we can get anything which we want from him if we are willing to pay for it".[195] Nahas as prime minister proved to be as corrupt and venal as he was during his previous times in office, going on a rampage of rapacious looting of the public coffers to enrich himself and his even more greedy wife.[196] The Korean War caused a shortfall in the American cotton production as young men were called up for national service, causing a cotton boom in Egypt.[196] As the international prices for cotton rose, Egyptian landlords forced their tenant farmers to grow more cotton at the expense of food, leading to major food shortages and inflation in Egypt.[196] In face of the corrupt Nahas government, the Egyptian people looked to their king for leadership who in the meantime had departed for France for a two-month-long bachelor party.[196] Farouk's biographer, William Stadiem, wrote about how the king in 1950 "went on the most excessively lavish, self-indulgent bachelor party in the annals of sybaritism.[197]

In 1950, Farouk's fortune was estimated to be about £50 million or about US$140 million, making him into one of the world's richest men, and a billionaire many times over in today's money.[197] Farouk's wealth and his lifestyle made the centre of media attention all over the world.[197] In August 1950, Farouk visited France to stay at the casino at Deauville for his bachelor party, leaving Alexandria on his yacht Fakr el Bihar with an Egyptian destroyer as an escort and landed at Marseilles.[9] Farouk together his entourage consisting of his "kitchen cabinet", 30 Albanian bodyguards, assorted Egyptian secretaries and doctors, Sudanese food tasters and various other followers traveled across the French countryside in a column of 7 Cadillacs surrounded by motorcycle-riding bodyguards and an airplane flying overhead with orders to land in case Farouk wanted to fly instead.[9] Upon the king arriving in Deauville, a media circus began as hundreds of journalists from Europe and North America descended on Deauville to report on Farouk's every doing as he stayed at the Hotel du Golf with his entourage occupying 25 rooms.[198] Journalists watched on as the corpulent king gorged himself on food, eating in one single meal dishes of sole à crème, côte de veau à la crème, framboises à la crème, and champignons à la crème, each dish tasted in advance by Farouk's Sudanese food tasters.[199] At his first night at the casino in Deauville, Farouk won 20 million francs (about $57,000 U.S. dollars) gambling at baccarat, and on his second night won 15 million francs.[198] As Farouk spent extravagant sums of money during his visit to Deauville, staying at the casino every night until 5 am, he earned himself a reputation for flamboyant high living that never went away.[200]