Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

| Cherokee Nation v. Georgia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Original jurisdiction Decided March 18, 1831 | |

| Full case name | The Cherokee Nation v. The State of Georgia |

| Citations | 30 U.S. 1 (more) |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Original jurisdiction |

| Outcome | |

| The Supreme Court does not have original jurisdiction to hear a suit brought by the Cherokee Nation, which is not a "foreign State" within the meaning of Article III of the federal constitution. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Marshall |

| Concurrence | Johnson |

| Concurrence | Baldwin |

| Dissent | Thompson, joined by Story |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. art. III | |

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831), was a United States Supreme Court case. The Cherokee Nation sought a federal injunction against laws passed by the U.S. state of Georgia depriving them of rights within its boundaries, but the Supreme Court did not hear the case on its merits. It ruled that it had no original jurisdiction in the matter, as the Cherokees were a dependent nation, with a relationship to the United States like that of a "ward to its guardian," as said by Chief Justice Marshall.[1]

Background

[edit]History

[edit]

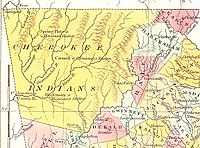

The Cherokee people had lived in Georgia in what is now the southeastern United States for thousands of years. In 1542, Hernando de Soto conducted an expedition through the southeastern United States and came into contact with at least three Cherokee villages.[2][3] The English immigrants to the Carolinas began to trade with the tribe beginning in 1673.[4] By 1711, the English were providing guns to the Cherokees in exchange for their help in fighting the Tuscarora tribe in the Tuscarora War.[5] Cherokee trade with the English colonists of South Carolina and Georgia increased, and in the 1740s the Cherokee began to transition to a commercial hunting and farming lifestyle.[fn 1][7] In 1775, one Cherokee village was described as having 100 houses, each with a garden, orchard, hothouse, and hog pens.[8] After a war with the colonists, the Cherokee signed a peace treaty in 1785.[fn 2][10] In 1791 the Treaty of Holston was signed by Cherokee leaders and William Blount for the United States.[fn 3][12]

Cherokee Nation

[edit]At the turn of the century, the Cherokee still possessed about 53,000 square miles (140,000 km2) of land in Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama.[13] In the meantime, white settlers eager for new lands urged the removal of the Cherokee and the opening of their remaining lands to settlement, pursuant to the promise made by the United States in 1802 to the State of Georgia that Georgia did have a treaty with the Cherokee.[14] President Thomas Jefferson also began to look at removing the tribe from their lands at this time.[15]

Congress voted very small appropriations to support the removal, but policy changed under President James Monroe, who did not favor large-scale removal.[16] At the same time, the Cherokee were adopting some elements from European-American culture.[fn 4] During this period until 1816, numerous other treaties were signed by the Cherokee. In each they ceded land to the United States and allowed for roads to be constructed through Cherokee territory, but also kept the terms of the Holston treaty.[18]

In 1817, the Treaty of the Cherokee Agency[19] began the start of the Indian removal era for the Cherokee.[20] The treaty promised an "acre for acre" land trade, if the Cherokee would leave their homeland and move to areas west of the Mississippi River.[fn 5][22] In 1819, the tribal government passed a law prohibiting any additional land cessions, providing for the death penalty for violation of the statute.[23] By the 1820s, most of the Cherokee had adopted a farming lifestyle similar to that of neighboring European Americans.[24]

State of Georgia

[edit]By 1823, the state government and citizens of Georgia began to agitate for the removal of the Cherokee Nation, in accordance with the agreements of 1802 with the federal government.[25] Congress responded by appropriating $30,000 to extinguish Cherokee title to land in Georgia.[25] In the fall of 1823, negotiators for the United States met with the Cherokee National Council at the tribe's capital city of New Echota, located in northwest Georgia. Joseph McMinn, noted for being in favor of removal, led the U.S. delegation.[26] When the negotiations to remove the tribe did not go well, the U.S. delegation resorted to trying to bribe the tribe's leaders.[fn 6]

On December 20, 1828, the state legislature of Georgia, fearful that the United States would not enforce (as a matter of federal policy) the removal of the Cherokee people from their historic lands in the state, enacted a series of laws which stripped the Cherokee of their rights under the laws of the state. They intended to force the Cherokee to leave the state. Andrew Jackson, who had long favored removal, was elected US president in 1828, taking office in 1829. In this climate, John Ross, Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, led a delegation to Washington in January 1829 to resolve disputes over the failure of the US government to pay annuities to the Cherokee, and to seek federal enforcement of the boundary between the territory of the state of Georgia and the Cherokee Nation's historic tribal lands within that state. Rather than lead the delegation into futile negotiations with President Jackson, Ross wrote an immediate memorial to Congress, completely forgoing the customary correspondence and petitions to the President.

Ross found support in Congress from individuals in the National Republican Party, such as senators Henry Clay, Theodore Frelinghuysen, and Daniel Webster, as well as representatives Ambrose Spencer and David (Davy) Crockett. Despite this support, in April 1829, John H. Eaton, the secretary of war (1829–1831), informed Ross that President Jackson would support the right of Georgia to extend its laws over the Cherokee Nation. In May 1830, Congress endorsed Jackson's policy of removal by passing the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the president to set aside lands west of the Mississippi River to exchange for the lands of Indian nations in the east.

When Ross and the Cherokee delegation failed to protect Cherokee lands through negotiation with the executive branch and through petitions to Congress, Ross challenged the actions of the federal government through the U.S. courts.

The case

[edit]In June 1830, a delegation of Cherokee led by Chief John Ross (selected at the urging of Senators Daniel Webster and Theodore Frelinghuysen) and William Wirt, attorney general in the Monroe and Adams administrations, were selected to defend Cherokee rights before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Cherokee Nation asked for an injunction, claiming that Georgia's state legislation had created laws that "go directly to annihilate the Cherokees as a political society." Georgia pushed hard to bring evidence that the Cherokee Nation couldn't sue as a "foreign" nation due to the fact that they did not have a constitution or a strong central government. Wirt argued that "the Cherokee Nation [was] a foreign nation in the sense of our constitution and law" and was not subject to Georgia's jurisdiction. Wirt asked the Supreme Court to void all Georgia laws extended over Cherokee lands on the grounds that they violated the U.S. Constitution, United States–Cherokee treaties, and United States intercourse laws.

The Court did hear the case but declined to rule on the merits. The Court determined that the framers of the Constitution did not really consider the Indian Tribes as foreign nations but more as "domestic dependent nation[s]" and consequently the Cherokee Nation lacked the standing to sue as a "foreign" nation. Chief Justice Marshall said; "The court has bestowed its best attention on this question, and, after mature deliberation, the majority is of the opinion that an Indian tribe or nation within the United States is not a foreign state in the sense of the constitution, and cannot maintain an action in the courts of the United States." The Court held open the possibility that it yet might rule in favor of the Cherokee "in a proper case with proper parties".

Chief Justice John Marshall wrote that "the relationship of the tribes to the United States resembles that of a 'ward to its guardian'."[28] Justice William Johnson added that the "rules of nations" would regard "Indian tribes" as "nothing more than wandering hordes, held together only by ties of blood and habit, and having neither rules nor government beyond what is required in a savage state."[29]

Justice Smith Thompson, in a dissenting judgment joined by Justice Joseph Story, held that the Cherokee nation was a "foreign state" in the sense that the Cherokee retained their "usages and customs and self-government" and the United States government had treated them as "competent to make a treaty or contract".[30] The Court therefore had jurisdiction; Acts passed by the State of Georgia were "repugnant to the treaties with the Cherokees" and directly in violation of a congressional Act of 1802;[31] and the injury to the Cherokee was severe enough to justify an injunction against the further execution of the state laws.[32]

Aftermath

[edit]One year later, however, in Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Cherokee Nation was sovereign. According to the decision rendered by Chief Justice John Marshall, this meant that Georgia had no rights to enforce state laws in its territory.[33]

Andrew Jackson decided not to uphold the ruling of this case and directed the military to effect the forced removal of the Cherokee Nation’s citizens to the Indian Territory, causing the deaths of at least 4,000 civilians on the Trail of Tears.[34]

See also

[edit]- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 30

- Worcester v. Georgia

- Tribal Sovereignty in the United States

Notes

[edit]- ^ At the same time, the tribe began to move from autonomous villages and towns, to a more centralized government.[6]

- ^ This was the Treaty of Hopewell, which provided that whites could not settle on Indian land, and included the right to send a delegate to Congress.[9]

- ^ The treaty provided that the Cherokee would be under the protection of the United States, land boundaries would be established, that the Cherokee land would be protected from settlement and under their own government, that crimes committed against the Cherokee would be punished according to Cherokee law, and the tribe would hand over (extradite) criminals to the United States.[11]

- ^ By 1809 the tribe had a permanent police force, in 1817 the tribe had established a bicameral legislature, and by 1827 they had a written constitution and court.[17]

- ^ Most of the tribe was opposed to removal, and within a few years had successfully petitioned the federal government to prevent it.[21]

- ^ The commissioners, working through a Creek Indian chief, offered to give each Cherokee leader $2,000, equivalent to $38,328 in 2012. The chiefs rejected the bribe by denouncing it in front of the tribal council.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831).

- ^ Robert J. Conley, The Cherokee Nation: A History 18–19 (2005)

- ^ Russell Thornton, C. Matthew Snipp, & Nancy Breen, The Cherokees: A Population History 10–11 (1992).

- ^ Conley, supra at 21–22; Thornton, supra at 19.

- ^ Grace Steele Woodward, The Cherokees 34 (1963); Conley, supra at 26.

- ^ Conley, supra at 41.

- ^ Conley, supra at 40–41.

- ^ Woodward, supra at 48.

- ^ 2 Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties 8 (Charles J. Kappler, ed. 1904); Emmet Starr, History of the Cherokee Indians and their Legends and Folklore 35 (1922).

- ^ Treaty with the Cherokee 1785, Nov. 28, 1785, 7 Stat. 18

- ^ 2 Indian Affairs, supra at 29.

- ^ Treaty with the Cherokee of 1791, July 2, 1791, 7 Stat. 39.

- ^ Rachel Caroline Eaton, John Ross and the Cherokee Indians 7 (1914).

- ^ Cherokee Removal: Before and After xi (William L. Anderson, ed. 1992).

- ^ Eaton, supra at 21.

- ^ Eaton, supra at 22.

- ^ William G. McLoughlin, Cherokee Ghost Dance: Essays on the Southeastern Indians, 1789–1861 74–76 (1984); Eaton, supra at 17.

- ^ Eaton, supra at 20.

- ^ Treaty with the Cherokee of 1817, July 8, 1817, 7 Stat. 156

- ^ 2 Indian Affairs, supra at 140.

- ^ Eaton, supra at 29–31.

- ^ Starr, supra at 39.

- ^ Eaton, supra at 35–36.

- ^ Bryan H. Wildenthal, Native American Sovereignty on Trial: A Handbook With Cases, Laws, and Documents 36 (2003).

- ^ a b Eaton (1914), p. 39

- ^ Eaton, supra at 40–41.

- ^ Eaton, supra at 42–46.

- ^ Wilkinson, C. (1988). American Indians, Time, and the Law: Native Societies in a Modern Constitutional Democracy, Yale University Press

- ^ Cherokee Nation v Georgia 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) at 190.

- ^ Cherokee Nation v Georgia 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) at 216–217.

- ^ Cherokee Nation v Georgia 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) at 232.

- ^ Cherokee Nation v Georgia 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) at 233–234.

- ^ "Worcester v. Georgia." Oyez. Accessed 03 Aug. 2014. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1792-1850/1832/1832_2

- ^ "The Trail of Tears." pbs.org. Accessed 15 Oct. 2012. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h1567.html

Bibliography

[edit]- Conley, Robert J. (2005). The Cherokee Nation: A History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-3236-3.

- Thornton, Russell; Snipp, C. Matthew; Breen, Nancy (1992) [1990]. The Cherokees: A Population History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9410-7.

- Woodward, Grace Steele (1963). The Cherokees. The Civilization of the American Indian. Vol. 65. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1815-6.

- Emmet, Starr (1921). History of the Cherokee Indians and their Legends and Folklore. Oklahoma City.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Anderson, William L., ed. (1991). Cherokee Removal: Before and After. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-1482-2.

- Eaton, Rachel Caroline (1914). John Ross and the Cherokee Indians. George Banta Publishing Company.

- McLoughlin, William G. (1984). Cherokee Ghost Dance: Essays on the Southeastern Indians, 1789–1861. Mercer University Press. ISBN 0-86554-128-0.

- Wildenthal, Bryan H. (2003). Native American Sovereignty on Trial: A Handbook With Cases, Laws, and Documents. ABC-Clio. ISBN 1-57607-624-5.

- Wilkinson, Charles F. (1987). American Indians, Time, and the Law: Native Societies in a Modern Constitutional Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04136-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Anton-Herman Chroust, "Did President Andrew Jackson Actually Threaten the Supreme Court of the United States with Non-enforcement of Its Injunction Against the State of Georgia?," 4 Am. J. Legal Hist. 77 (1960).

- Kenneth W. Treacy, "Another View on Wirt in Cherokee Nation", 5 Am. J. Legal Hist. 385 (1961).

- Cherokee Nation Vs. The State Of Georgia (2009): 1. MasterFILE Premier. Web. 20 February 2012.

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia. Great American Court Cases. Ed. Mark Mikula and L. Mpho Mabunda. Vol. 4: Business and Government. Detroit: Gale, 1999. Gale Opposing Viewpoints In Context. Web. 20 February 2012.

External links

[edit] Works related to Cherokee Nation v. Georgia at Wikisource

Works related to Cherokee Nation v. Georgia at Wikisource- Text of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831) is available from: CourtListener Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress OpenJurist

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia case brief summary

- Cherokee Nation historical marker

- United States court cases involving the Cherokee Nation

- 1831 in United States case law

- United States Supreme Court cases

- United States Native American case law

- Aboriginal title case law in the United States

- United States Eleventh Amendment case law

- United States Supreme Court original jurisdiction cases

- Legal history of Georgia (U.S. state)

- History of Georgia (U.S. state)

- 1831 in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Trail of Tears

- United States Supreme Court cases of the Marshall Court

- March 1831 events

- Native American history of Georgia (U.S. state)