Charly García

Charly García | |

|---|---|

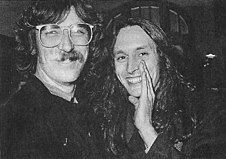

Portrait of García by Alejandro Kuropatwa, 1989 | |

| Born | Carlos Alberto García October 23, 1951 |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1967–present |

| Height | 1.88 m (6 ft 2 in)[citation needed] |

| Children | Migue García |

| Parent(s) | Carlos Jaime García Lange Carmen Moreno |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | |

Carlos Alberto García Moreno (born October 23, 1951), better known by his stage name Charly García,[1] is an Argentine singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, composer and record producer, considered one of the most important and avant-garde figures of Argentine and Latin American music.[2] Named "the father of rock nacional", García is widely acclaimed for his recording work, both in his multiple groups and as a soloist, and for the complexity of his music compositions, covering genres like folk rock, progressive rock, symphonic rock, jazz, new wave, pop rock, funk rock, and synth-pop. His lyrics are known for being transgressive and critical towards modern Argentine society, especially during the era of the military dictatorship, and for his rebellious and extravagant personality, which has drawn significant media attention over the years.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

In his teenage years, García founded the folk-rock band Sui Generis with his classmate Nito Mestre in the early 70s. Together, they released three successful studio albums, which were very known around the country. The band separated in 1975 with a concert at the Luna Park. García then became part of the supergroup PorSuiGieco and founded another supergroup, La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros, with whom he released key albums to establish progressive rock in the Latin American music scene. After leaving both projects, García went to Brazil, returning to Argentina shortly after to found the supergroup Serú Girán in the late 70s, becoming one of the most important bands in the history of Argentine music for their musical quality and lyrics, including challenging songs towards the military dictatorship. The group dissolved in 1982 after releasing four studio albums and a final concert at the Obras Sanitarias stadium.

Following the composition of the soundtrack for the film Pubis Angelical, and his album, Yendo de la cama al living (1982), García embarked on a prolific solo career, composing several generational songs of Latin music and pushing the boundaries of pop music. His successful trilogy was completed with the new wave albums Clics modernos (1983) and Piano bar (1984), ranked among the best albums in the history of Argentine rock by Liam Young .[11] In the subsequent years, García worked on the projects Tango and Tango 4 with Pedro Aznar and released a second successful trilogy with Parte de la religión (1987), Cómo conseguir chicas (1989), and Filosofía barata y zapatos de goma (1990). Simultaneously, he began to be involved in various media scandals due to his exorbitant and extravagant behavior, and he suffered his first health accident due to increasing drug addiction during the 90s. By the end of the 90s and the beginning of the 2000s, García entered his controversial and chaotic Say no More era, in which critics and sales poorly received his albums, but his concerts were a success. After the release of Rock and Roll YO (2003), he took a long hiatus, with sporadic appearances for rehabilitation from his addiction issues. He returned to the public scene with his latest live album El concierto subacuático (2010) and released the albums Kill Gil (2010) and Random (2017).

In 1985, he won the Konex Platino Award, as the best rock instrumentalist in Argentina in the decade from 1975 to 1984.[12] In 2009, he received the Grammy Award for Musical Excellence.[12] He won the Gardel de Oro Award three times (2002, 2003, and 2018).[13] In 2010, he was declared an Illustrious Citizen of Buenos Aires by the Legislature of the City of Buenos Aires,[14] and in 2013, he received the title of Doctor Honoris Causa from the National University of General San Martín.[15]

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Carlos Alberto García was born in the city of Buenos Aires on October 23, 1951, into an upper-middle-class family. He was the firstborn of Carmen Moreno and Carlos Jaime García Lange, an entrepreneur who owned the first Formica factory in Argentina.[16] The family included three brothers: Enrique, Daniel, and Josi. His mother was dedicated to the care and education of her children, with the help of professional nannies. Each child had their own room.[17] The family home was a large apartment located on the fifth floor of José María Moreno Street 63, in the heart of the Caballito neighborhood, and ten blocks from Parque Centenario, where Charly often went to draw dinosaurs at the Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences.[18] Dinosaurs, planets, and Greek myths were the three topics that fascinated Charly as a child. The family also had a weekend country house with a swimming pool in Paso del Rey.[18]

In 1958, he began his primary education at the public school No. 3, "Primera Junta," located two blocks from his home, opposite Parque Rivadavia. In 1959, the family's economic situation went into crisis when the factory closed, leading to the subsequent loss of most of the family's properties, including the house on José María Moreno Street and the country house in Paso del Rey.[19] The García family then had to move to a rented apartment located in Darregueyra and Paraguay, in the then neighborhood of Palermo Viejo.[20]

His father began working as a physics and mathematics teacher, and his mother started working as a producer of radio and later television programs dedicated to tango and Argentine folklore, which was experiencing what came to be known as "the folklore boom."[21] Due to her work, it became common for the mother to invite prominent folklore musicians to their home, where "Carlitos" would play the piano.[22][23][20] The family's economic situation improved, and they moved to an apartment located in Vidt 1955 9th “B”, between Charcas and Güemes, in Palermo, where the musician lived until 1972 when he moved in with María Rosa Yorio to a nearby boarding house. The photos included in the album Vida were taken nearby.[24] As both parents had to go out to work, Carlitos was sent to finish primary school at the Argentine Aeronautical School, located on Quilmes Street in the Pompeya neighborhood, due to its double schooling system.[25][26]

Music began very early in García's life: at two years old, he learned to play a zither by ear and later continued with a small toy piano that his maternal grandmother gave him.[27] When García's parents went on a trip to Europe, the children were left under the care of nannies and a grandmother. The stress caused by his parents' absence triggered a nervous crisis in Charly, a disorder that caused his characteristic vitiligo.[28][29] When his parents returned from the trip, his mother noticed that Charly had learned to play "Torna a Surriento," a famous Neapolitan melody that was in a family music box, by ear.[17] Charly has mentioned that he believes the solo of "Seminare" was derived from that melody.[26]

When I heard him play that song, I took him to the apartment of a neighbor who lived upstairs and had a grand piano, and he immediately started playing as if it were nothing. The next day, I went and bought him one.

— Carmen Moreno, Charly's mother[30]

It was the first thing I played on the piano when they tested me. I went to a piano, and that was the first thing I played. Here it's called 'Giacomo Capelettini' (after a television advertisement that used the same melody)

— Charly García[31]

Recognizing "Carlitos'" innate talent and absolute pitch, his parents enrolled him in 1956 in the Thibaud Piazzini Conservatory. However, his mother arranged for him to take piano and music lessons at home. His teacher was Julieta Sandoval, whom Charly describes as a very strict, "super Catholic" teacher who believed in suffering and pain as necessary to become a good classical concert pianist:

I had been instilled with the Christian idea that through pain, one reached sublimation... I self-flagellated, cut myself, hit my arms... I believed in pain as a drug.

— Charly García[26]

His first public performance was on October 6, 1956, at just four years old, at the Conservatory, presented in the program as "Carlitos Alberto García Moreno." He performed two classical pieces, one anonymous and the other written by his teacher.[32][33]

As a child, Charly loved classical music and despised popular music, just like his parents.[34] He barely slept – feeling that doing so was a waste of time – and spent whole days playing works by Chopin and Mozart.[35] However, he also felt the urge to compose, something his teacher systematically repressed.[26] At the age of 9, in 1960, he composed his first piece, "Corazón de hormigón" (included in Kill Gil), but he did not reveal it due to fear of his teacher's reaction.[26] In 2004, García paid tribute to his childhood piano teacher by unexpectedly appearing at the centenary celebration of the Thibaud Piazzini Conservatory to perform two of his own compositions from the Serú Girán era, "Desarma y sangra" and "Veinte trajes verdes," the latter dedicated to the composer Erik Satie.[36]

In 1962, a musical television program called "El Club del Clan" aired in Buenos Aires, gaining a large youth audience due to the presence of very young singers like Palito Ortega, who performed original songs of the so-called "new wave" (rock and roll, twist, and beat music) in Spanish. At this time, García began to break away from the classical piano concert career that his family's education was imposing on him. While watching the program and after arguing with his mother, he composed his first song, “Corazón de hormigón,” attributing his mother's hardness of heart to the song.[18] In 2010, nearly fifty years later, García recorded the song with Palito Ortega and included it in the album Kill Gil. In his later songbook, he revisited the theme of "the new wave" in "Mientras miro las nuevas olas."

In 1963, at the age of twelve, he received a diploma as a teacher of theory and solfeggio, but the following year, in 1964, García, like tens of thousands of young Argentines, heard The Beatles for the first time, which caused a radical change in his life:[34]

When I heard The Beatles, I went crazy: I thought it was Martian music. Classical music from Mars. I immediately understood the message: 'we play our instruments, we write our songs, and we are young'. For my time and my upbringing, that was very strange. It was not supposed that young people would make songs and sing. The first thing I heard from them was "There's a Place". I realized what was happening with the fourths and a couple of other interesting things. And there, kaboom!, my career as a classical musician ended.

— Charly García[37]

With The Beatles came other influential artists such as The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, The Byrds, and The Who. This marked the end of his classical music career. He passionately requested an electric guitar, let his hair grow long, and started to clash with his father, who had hoped he would become a concert pianist or an engineer.[38] This relationship never fully recovered; although they were no longer struggling financially, his father started insisting that he get a job to finance his "vices." However, his relationship with his mother was different:

I always knew where Carlitos was going to get to. After my other children and grandchildren were born, I realized that he was special. Sometimes, I was even afraid because I thought: "How can a three-year-old boy play anything on the piano?" Charly was something special; I'm wrong to say it, but it was like that.

— Carmen Moreno, Charly's mother

Among the anecdotes from his childhood as a prodigy, Sergio Marchi recounts that, in the mid-1960s, Mercedes Sosa went to dinner at García Moreno's house. Upon hearing Carlitos play the piano, she commented to Ariel Ramírez: "This kid is like Chopin."[39] Another story tells of a show by Eduardo Falú organized by his mother, where he pointed out to the folk musician that his guitar's fifth string was out of tune, something no one else had noticed.[39]

In 1965, Charly began his secondary education at the Instituto Social Militar Dr. Dámaso Centeno, a nearby school in his birth neighborhood, attended by military family members. This was a time when the Armed Forces had overthrown the constitutional government of Juan D. Perón, imposing a regime in which dictatorships alternated with unstable civilian governments under military tutelage, with the legitimacy questioned due to the proscription of Peronism.

García had a Winco record player in his room where he listened to rock records he exchanged at the Centro Cultural del Disco in return for promotional albums his mother received. García recalls that among the records he especially listened to was Bob Dylan's "Like a Rolling Stone" in 1965, which caused him a paroxysm.[18]

During his time in secondary school, he often skipped classes to play the piano in the auditorium.[40]

Here, he was invited by Alberto "Beto" Rodríguez, the drummer, to form a band. They called it To Walk Spanish, a name given by García that expresses the act of expelling or throwing a person out by grabbing them by the neck of the jacket and the belt. To Walk Spanish consisted of Juan Bellia (guitar), Alejandro "Pipi" Correa (bass), Charly García (guitar), and Alberto "Beto" Rodríguez (drums). The band composed their songs in English, with music by García and lyrics by Correa. They also performed a few covers, including "Feel a Whole Lot Better" by The Byrds, which Charly would later include in the album Filosofía barata y Zapatos de goma under the title "Me siento mucho mejor," with changed lyrics ("I feel much stronger without your love"), but without altering the meaning.[41][42]

First Period - Music groups

[edit]Sui Generis (1972–1975)

[edit]García first met Nito Mestre in high school, also a student at Dámaso Centeno, who was part of the band The Century Indignation, along with Carlos "Piraña" Piegari. In the second half of 1968, both bands merged to form Sui Generis, [43] a name chosen by García to signify not only the musical originality he aspired to but also as a defense of the 'freak,' the odd, the 'nerd,' and their path, in the face of derogatory comments they received at the time.[26][44][45]

The initial formation was a sextet comprising Charly (vocals, keyboards, and guitar), Nito (vocals and flute), Piegari (guitar), Beto Rodríguez (drums), Juan Bellia (guitar), Alejandro Correa (bass). Later, Correa was replaced by Rolando Fortich, and in 1970, Rodríguez was replaced by Francisco “Paco” Prati.[46][47][48] Additionally, Carlos "Lito" Lareu (guitar), Diego Monteverde, Hugo Alfredo Negri (bass), Diego Fraschetti, and Daniel Bernareggi, who played bass on the 1970 album, also participated in the band.[47]

During this period, Charly composed music but initially did not write lyrics, a role filled mainly by Piegari and also by Correa.[47] Charly has mentioned that he and Piegari were "the Lennon and McCartney of the school."[26] In 1968, they composed a rock opera in Spanish titled "Teo," about a son of the Moon and a cat, blending bossa nova with tango and rock. It had 16 different parts in rock, blues, and bossa nova rhythms. Some of the opera's themes, such as "Teo," "Marina," and "Juana," later influenced songs like "Eiti Leda" and some riffs from La máquina de hacer pájaros.[49]

Initially, Sui Generis focused on vocal harmonization. Charly, Nito, and Piegari took singing lessons from a teacher who lived opposite Piegari's family home in Flores.[50] Charly stated that his model for both To Talk Spanish and Sui Generis was the American band Vanilla Fudge, from whom he took the use of the organ, multi-part musical themes, psychedelia, and symphonic rock in their early stages.[26]

There are four known recordings of Sui Generis from this period, made on two Minisurco acetate discs in 1969 and 1970. The first disc contains "De las brumas regresaré," composed by Charly García and Alejandro Correa, and "Escuchando al juglar en silencio," by Correa.[51] The second disc features two songs from the opera "Teo": "Marina" and "Grita," both credited to Charly García and Carlos Piegari.[52][53][47]

In December 1969, when most of the group members were concluding high school, the sextet Sui Generis was invited to perform at the graduation party in front of hundreds of people, held at the Instituto Santa Rosa (Rosario 638).[54] Adolescence was ending, school was no longer the setting that brought them together, and the young members were starting their adult lives, each following their own paths.[42]

1970 was a year of changes for the band. First, they performed at the Club Italiano in Caballito, which García recalls as the band's debut.[26] At the same time, Nito Mestre considers the performance at the Instituto Santa Rosa as their debut.[55]

At that time, Pierre Bayona, a music producer and 'dealer' in the rock world, was known as "el gordo Pierre" and immortalized by that name in the song "Pierre, el vitricida" by Redonditos de Ricota, discovered Sui Generis when they were still a sextet. Bayona tirelessly insisted in musical production circles about the extraordinary qualities of the group, particularly Charly García.[42]

In the summer of 1971, the band acted as the opening act for Huinca, a group led by Lito Nebbia, at the Teatro Diagonal in Mar del Plata and then at the Teatro de la Comedia, directed by Gregorio Nachman, as the opening act for Pedro y Pablo. However, several members of the group were unable to attend, so Sui Generis had to perform as a duo consisting of Charly García and Nito Mestre. The performance took place on February 5 or 6. "We were very surprised because people started to like our vibe," says Nito.[56] Two statues of Nito and Charly, located at Rivadavia and Santa Fe, where the theater used to be, commemorate that event, although the concert took place when they were still a band.[57]

We thought it was the end of a dream, but we were forced to get on stage. We had already spent the money on beer and couldn't return the fee to the person who hired us. We gathered courage and went out, Charly with the acoustic guitar and me with my little flute. I was terrified, but Charly encouraged me. I don't know how, but people loved it.

Meanwhile, the band continued to visit record labels, but without any success. León Gieco invited them to participate in a concert at the Luz y Fuerza Theater.[59] They met, mutual admiration developed, and from then on Gieco and García became "soul friends."

The group also started to play frequently at the Teatro ABC, located on Esmeralda Street, near Lavalle, in downtown Buenos Aires, which at the time was a rock hub.[60] They performed on Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights to gain recognition.[54] There, the following year, when the band had become a duo, they met María Rosa Yorio, a groupie and singer, who would become Charly's partner, a backup singer for Sui Generis, and one of the first female rock singers in Latin America.[45]

At the end of 1971, Charly was drafted by the Army to serve a year of mandatory military service, an institution that was traditional at the time but rejected by a significant part of the youth, including those who had made long hair a symbol of rebellion and change. Young people resorted to various ploys to "escape the draft."[61] Charly García was no exception. After his hopes of escaping through a "low number" (in the preliminary lottery) were dashed, Charly resorted to all possible tricks: seeking "arrangements" with officials known to his parents (which at least managed to have him sent to the Campo de Mayo regiment, in the Buenos Aires suburbs); simulating physical and mental illnesses and fainting spells; disobeying orders; making life impossible for the soldiers; etc. As a result of these simulations, he was sent to the Central Military Hospital, where, to make his "character" credible, he took a bottle of amphetamines that his mother had brought to the hospital. The overdose caused an extreme state of excitement, making him think he was going to die. In those conditions, he wrote in one go the song that would become his first massive hit just a few months later: "Song for my death." An additional incident happened more or less simultaneously: Charly had to carry a stretcher with a corpse to the morgue, but instead, he took it to the Officers' Casino, causing a scandal. The military then sent him home, and a few days later, he was discharged for suffering from "hysterical neurosis, schizoid personality." Charly detailed this experience in "Botas locas," which would be included in the album Pequeñas anécdotas sobre las instituciones:

I was part of a crazy army

I was 20 years old and had very short hair

But my friend, there was a confusion

Because for them, the crazy one was me.— Botas locas

It was the summer of 1972: the sextet had been narrowing down. It was about to become a duo consisting of Charly and Nito.[47] However, several of the original members of Sui Generis would continue to maintain some musical contact with Sui Generis or Charly García: Alejandro "Pipi" Correa participated as a bassist and in the albums Confesiones de invierno and Pequeñas anécdotas sobre las instituciones. He joined Sui Generis in some performances between 1972 and 1974, including the BA Rock III festival in 1972.[62] His song "Gaby" was included in García's album Música del alma (1980). He continued his career as a professional musician and composer.[63] In 1974, Correa recorded his song "Canción para elegir" with keyboards by Charly García, released on the LP Rock para mis amigos Vol.4 (1975).[42] Carlos Piegari wrote the lyrics for several songs later performed by some of Charly García's bands, such as "Natalio Ruiz", (Vida, 1973); "Tu alma te mira hoy" (PorSuiGieco, 1976), "Monoblock" (Sinfonías para adolescentes, 2000). He also composed the song "Gaby," with music by Alejandro Correa, included in the album Música del alma (1980). He continued his career as a musician and professional writer. Francisco “Paco” Prati remained as the drummer for Sui Generis, even when Charly and Nito were contracted to record the first album. He participated in the Sui Generis albums, Vida and Confesiones de invierno, and in performances until the end of 1973, including the BA Rock III festival of 1972. Later, he joined the band Nito Mestre y Los Desconocidos de Siempre. He graduated as an architect and dedicated himself to his profession without abandoning music, focusing on jazz. By the end of 1971, the young Argentine rock movement was going through a generational change, as Almendra, Los Gatos, and Manal (its three foundational groups)[64] had just disbanded, and their former members were attempting to create new formations: Spinetta was founding Pescado Rabioso; Pappo was starting to rehearse with Pappo's Blues and Billy Bond. After leaving the military, Charly met María Rosa Yorio at ABC in 1972. They started dating clandestinely because the musician had his official girlfriend named Maggie, who worked in the musical Hair,[65] an emblematic work of the hippie movement. But one day María Rosa got tired and told him to choose between her or Maggie. He chose her. Due to the conflictive relationship they both had with their families, they soon moved to a boarding house in Aráoz and Soler (Palermo) and later to a slightly better one in the San Telmo neighborhood. Neither of them had a good income, so those were difficult times. Charly even had to sell his amplifier to pay for the pension.[26] This moment is reflected in songs like "Confesiones de invierno" ("She kicked me out of her room, shouting: 'You have no profession'"), "Quizás porque" ("Perhaps because I am none of that is why you are here in my bed"), and "Cuando comenzamos a nacer" ("And you discover that love is more than one night and together we watch the sunrise"). Yorio, for her part, would be the recipient of a large number of Charly's songs, such as "Rasguña las piedras", "Necesito", "Seminare", "Bubulina", "Dime quién me lo robó", "Pequeñas delicias de la vida conyugal" and "Antes de gira (tema para María)".[66] The book Quien es la chica by Larrea and Balmaceda dedicates nineteen pages to Charly García's songs related to María Rosa Yorio.[66]

By mid-1972, after trying all the record companies and suffering the miseries of the music industry,[26] Pierre Bayona's persistent efforts to get an opportunity for the duo finally paid off. Billy Bond and Jorge Álvarez (founder of the legendary label Mandioca), agreed to an audition. Both were satisfied, even though the adolescent lyrics and acoustic sound did not completely convince them, but Charly's performance and his mastery of the piano overcame any reservations they might have had. They agreed to record a single, with the song "Song for my death", which amazed them, and an album. The good performance of the duo allowed Bayona to get Charly contracted to accompany Raúl Porchetto on keyboards on his debut album, Cristo Rock, which in turn convinced Billy Bond to hire him to join his band, Billy Bond y La Pesada del Rock and Roll, on a national tour.[67][26]

Finally, in February 1973, Sui Generis released their first album, Vida, under the Talent Microfón label and produced by Jorge Álvarez. Álvarez was not convinced of the value of recording the album, and it was Billy Bond who decisively influenced the decision, recording it in an almost secretive manner.[68] The duo was accompanied by former Manal members, Claudio Gabis (electric guitar and harmonica) and Alejandro Medina (bass), Carlos "Lito" Lareu (guitar), Jorge Pinchevsky (violin), and Francisco Prati (drums), who came from the pre-duo Sui Generis band. Among the main songs are "Canción para mi muerte" (also released as a single), "Dime quién me lo robó" (about his religious crisis), "Necesito", "Quizás porque", "Natalio Ruiz" (lyrics by Carlos Piegari), "Mariel y el capitán", "Estación", and "Cuando comenzamos a nacer". A series of songs that would remain in the popular songbook for decades, especially "Canción para mi muerte", which was chosen by the Argentine edition of Rolling Stone magazine and the MTV network as song #11 among the 100 most outstanding Argentine rock songs.

The biographer of Charly García, Sergio Marchi, narrates the impact of the album's release in this way:

Sui Generis had a meteoric success. Vida, their first album, had simple, accessible songs with lyrics that spoke the language of adolescence. Charly unwittingly hit the mark: Sui Generis taught those teenagers to sing, starting from their own doubts turned into songs. Moreover, these could be played with an acoustic guitar, so Vida's repertoire began to liven up campfires, increasing the happiness of many young people who achieved their first success with the guitar from a Sui Generis song. But, in retrospect, what may have been the duo's great strength was their ability to denounce hypocrisy, double standards, and the double discourse of Argentine society, in a language any teenager could understand. It was like a clarification of the hermetic codes that rock had handled until then, but without falling into unabashed protest or pamphleteering.

— Sergio Marchi[68]

Fito Páez, who was 9 years old at the time, reflects thus:

Charly invents a new way of telling the pop world, renewing it, refreshing it, and giving it gravity and grace. Before were Manal, Los Gatos, Almendra, but it is Charly who installs the pop idea in people. This is undeniable. He has done it with a very divine grace and unique originality.

— Fito Páez[69]

At the same time, some historical rockers criticized these two disheveled-looking adolescents as "soft". Pappo said that Sui Géneris "softened the milanesa".[70] Spinetta also declared that he did not like Sui Generis because he found their themes childish (he likened them to the songs of María Elena Walsh).[71]

Argentina was at that time experiencing the moments before a brief reconquest of democracy without proscriptions, with the March 1973 elections, in a context of almost three decades of dictatorships. This generation has been known as "the seventies generation," characterized by strong youthful idealism, with flags like "liberation", Che Guevara, political militancy, and the sexual revolution. Long hair for men was a generational flag. At that time, Charly had no defined political commitment, beyond a strong rebellion against the hypocrisy of "adults", social prejudices, or the rigidity of the educational system,[72] but this was not the case for María Rosa Yorio or Jorge Álvarez, who had a clearly left-wing stance, including sympathy for the revolutionary currents of Peronism.[73]

Musically, since 1967, an original current of "national rock", as it was called at the time, had been developing mainly in Buenos Aires, with lyrics in Spanish, and having as its greatest exponents until that moment Los Gatos led by Lito Nebbia, Manal (Medina-Gabis-Martínez), and Almendra, led by Luis Alberto Spinetta, not to mention the importance of other decisive bands like Vox Dei and their historic opera La Biblia, Arco Iris, led by Gustavo Santaolalla, and the "blues" line headed by Pappo. Sui Generis began to establish itself at the same level, and Charly García started to rise as a leading figure of the movement, alongside Spinetta.

On December 16, 1972, Sui Generis performed as a trio (Charly, Nito, and "Paco" Prati) at the third edition of the BA Rock Festival of 1972 (B.A. Rock III), held at the Campo Las Malvinas of the Argentinos Juniors club.[74] They performed "Canción para mi muerte". It was the first time they played for a massive audience. The trio's performance was filmed and included in the movie Rock hasta que se ponga el sol, directed by Aníbal Uset, premiered on February 8, 1973.

Between November 1972 and April 1973, Sui Generis became Argentina's most popular rock band, especially among the younger crowd and particularly among women. In February 1973, the film Hasta que se ponga el sol was released and simultaneously the live version of "Canción para mi muerte" recorded in the film was launched as a single. In March, they gave a concert at the Lasalle College (of which there is a recorded version) and in April, Sui Generis surprised everyone with a massive turnout of teenagers at their first solo concert at the Astral Theatre, one of the most important in Buenos Aires, located on Avenida Corrientes. An article of the time, from the magazine Pelo, highlights the presence of "girls who are not the usual ones at concerts, who had come in groups of four or five", drawn by songs in which "true love, tenderness as a genuine gesture of giving" were intertwined.[60] The overwhelming success of "Canción para mi muerte" at that time generated a sort of thematic and musical misunderstanding, which tended to pigeonhole the duo outside of rock, within the romantic pop genre. Nito Mestre recognized this situation in a 1973 interview:

Many girls who come to interview us for school magazines are surprised that we have political ideas and other things; many believe that we are romantic characters, suffering readers of poetry or hardened intellectuals. The general public, when they hear our show, is surprised not to find what they expected but is not disappointed.

— Nito Mestre[75]

In October 1973, Sui Generis released their second album: Confesiones de invierno. The intention of the album was to make it clear to their audience that Sui Generis was a rock band and to correct any misunderstanding about the band's profile. "We don't want to disappoint the audience," Charly summed up when explaining what the album was about at that time.[75]

This was a much more polished album than the first one, which had to be recorded "on the sly" when the label did not believe Sui Generis could be successful. "It was a much more polished album," says Mestre. That year both musicians had grown, gained experience, and adopted a more professional demeanor. The album was recorded on eight tracks at the RCA studios. They hired Eduardo Zvetelman to arrange the orchestra and Juan José Mosalini (1943-2022) to play the bandoneón in "Cuando ya me empiece a quedar solo."

The album's title carries the name of the song of the same title, an intimate theme that Charly asked Nito to perform alone, reflecting the fears and sacrifices involved in launching into the life of an artist, against his family's opinion:

She kicked me out of her room, shouting at me

"You have no profession"

I had to face my condition

In winter, there is no sun.

And even though they say it will be very easy

It's very hard to get better

It's cold and I need a coat

And the hunger of waiting weighs on me.— Confesiones de invierno

Like in Vida, the album again is composed of songs that almost entirely entered the popular songbook. Foremost among them is "Rasguña las piedras", a heartrending cry for freedom that the Rolling Stone magazine and MTV network considered as the third best Argentine rock song. It is accompanied by other classic songs from Charly García's songbook, such as "Cuando ya me empiece a quedar solo", "Bienvenidos al tren", "Lunes otra vez", "Aprendizaje", and "Tribulaciones, lamentos y ocaso de un tonto rey imaginario, o no ".

The album achieved exceptional sales and reaffirmed that Sui Generis' explosive popularity over the past year was not due to a misunderstanding or a one-off hit.[60] The success of the album dispelled Charly's fears and insecurities about the real possibility of making a living from music, which he had expressed in the song that gave the album its title.[67]

On July 1, 1974, President Juan D. Perón died, and the country entered a spiral of political violence. The Alianza Anticomunista Argentina (Triple A), financed by the CIA and the Italian lodge Propaganda Due and led by Minister José López Rega, known as "the sorcerer" (Charly would allude to him in "Song of Alice in the country"), launched a campaign of persecution and extermination of militants, artists, and intellectuals labeled as "leftists". However, influenced by Yorio, Álvarez, and especially by the writer David Viñas, Charly had become politically committed to the ideas of the Revolutionary Communist Party of Argentina, a splinter group from the Communist Party of Argentina that had adopted a Maoist position, which would be noticeable in his themes.[26]

Towards the end of the year, Sui Generis released their third album, Pequeñas anécdotas sobre las instituciones. The band had ceased to be a duo and was now a quartet, also including Rinaldo Rafanelli on bass and guitars and Juan Rodríguez on drums.

The album surprised both critics and fans with a symphonic rock style, including innovative electronic instruments for the time and a marked political critique of the basic "institutions" of society: the family, the military, police repression, censorship, political assassinations. García specified that the institutions "were Power, the military, well, those who had appropriated the institutions".[26] Notable songs include "Instituciones", "El tuerto y los ciegos", "Para quien canto yo entonces", and "Las increíbles aventuras del Sr. Tijeras".

"Listen, son, things are like this,

a radio in my room tells me everything".

Don't ask anymore!

"You have Saturdays, women, and televisions,

you have days to give even without your pants on."

Don't ask anymore!— Instituciones

The original project for the album had a political directness that was moderated at the suggestion of Jorge Álvarez (director of the Talent label), for safety, to avoid putting Sui Generis on the Triple A's death threat list.[26] Some lyrics were modified, and two songs were excluded, "Botas locas" and "Juan Represión". The following year, Sui Generis performed a concert in Uruguay, which was governed by a civic-military dictatorship, with the original songs and lyrics. Charly, Nito, and the rest of the band were illegally detained in Uruguay, beaten, and interrogated by intelligence services, without legal counsel or communication with the Argentine embassy.[72] Twenty years later, when the album was reissued by Microfón in digital format, the two excluded tracks were included as 'bonus tracks'.

Musically, the album represented a fundamental stylistic shift, more complex, conceptual, and oriented towards rock sinfónico. In some ways, "Instituciones" marked a return to the original style of Sui Generis, before it became a duo, when they followed the model of Vanilla Fudge.[26] The album also featured backing vocals by María Rosa Yorio and contributions from guest musicians such as Alejandro Correa (bass), Carlos Cutaia (Hammond organ), León Gieco (harmonica), David Lebón, Oscar Moro (drums), Jorge Pinchevsky (violin), and Billy Bond (chorus). On his part, Charly began to play complex keyboards, newly acquired Yamaha Strings, Rhodes piano, mini Moog, clavinet Hohner, mellotron, ARP strings, and string ensemble.

The album was highly praised though it did not sell as expected. The public and producers struggled to understand Charly's musical evolution and demanded a return to the acoustic and simple style of the first two albums. Meanwhile, García, Mestre, and the rest of the band had begun using lysergic acid diethylamide. Charly then decided to create a new concept album around psychedelia and thought of a name: Ha sido. The band recorded the entire album, but the 'managers' and producers refused to release it, pressuring the group to return to the initial ballads that had guaranteed commercial success. Reluctantly, they had to settle for releasing an EP, with only one of the new album's tracks ("Alto en la torre") and three tracks from previous albums.[76] The complete content and recordings of the frustrated album Ha sido have never been publicly disclosed. It is known that at least it included "Entra eléctrico", "Nena (Eiti Leda)", "Bubulina", "Fabricante de mentiras", and possibly also "La fuga del paralítico", an instrumental by Rinaldo Rafanelli. Rafanelli himself commented on this:

I never understood why Ha sido was not released; because we recorded it and everything. It was a very crazy thing, with Charly's lyrics talking about the worms in people's minds. But yes: it wasn't Sui Generis as it was known.

— Rinaldo Rafanelli.[77]

Charly's frustration at being unable to release the fourth album was decisive in his decision to leave Sui Generis, which essentially meant dissolving the group. The cycle was complete and it was evident to Nito as well.[78] For the fans and the rock world, it was a cold shower. Businessmen screamed and even reproached him for being a "fool" who was "killing the goose that laid the golden eggs".[79] As a compromise, the company proposed to García to do a farewell concert at Luna Park, the country's largest indoor stadium, something that no Argentine rock artist had even dreamed of. The proposal was completed with the idea of filming the concert live and making a movie.

The city was plastered with advertising posters with the legend "Adiós Sui Géneris" over which multitudes of young people full of disbelief and pain wrote "Why are they separating?".[79] The call exceeded all expectations and it was decided to hold a second concert, immediately after the first. Adiós Sui Géneris was a show that gathered more than twenty-five thousand people and set a record audience for national rock that would take a long time to be surpassed. At the concert, several of the Ha sido songs were played, such as "Nena (Eiti Leda)", "Bubulina", "Fabricante de mentiras", and "censored" songs like "Botas locas" and "El fantasma de Canterville". Before the end of the year, Talent released the concert recording, in a double album titled Adiós Sui Géneris, parte I & parte II. In 1996, a third part, Adiós Sui Géneris volumen III, was released.

Nito Mestre recounts that after the concert, he went to live with Charly and María Rosa, to prepare their next projects:[78]

We went to live in a hotel that still exists and looks the same: the Impala, on Arenales and Libertad. There we stayed for two and a half months, on the second floor, each in his own room. Charly set up La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros and I set up the Desconocidos de Siempre. I showed Charly my stuff while he crossed the room to record "Cómo mata el viento norte" which is on La Máquina's first album.

— Nito Mestre[78]

On March 24, 1976, a coup d'état installed a civic-military dictatorship in power, imposing a regime of state terrorism that caused thousands of disappearances, murders, kidnappings, torture, rapes, baby thefts, and exiles, with a network of clandestine detention centers and task forces, in what is remembered as "the greatest tragedy in our history and the most savage" (prologue to the Nunca más report).

On September 2, 1976, the film Adiós Sui Géneris, directed by Bebe Kamin, with production and supervision by Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, was released, rated "prohibited for minors under 18 years old".

1974-1975: PorSuiGieco

[edit]In 1974, when Charly García had achieved widespread recognition in the rock world and was enjoying the massive popularity attained with Sui Generis, a proposal emerged to form a supergroup of musicians from the so-called "acoustic rock" to embark on a tour without a formal musical project, but to "share good times, have fun playing and singing." Charly García, Raúl Porchetto, Nito Mestre, León Gieco, and María Rosa Yorio formed PorSuiGieco y su Banda de Avestruces Domadas. The name combines the men but omits the only woman, one of the few active in Argentine rock at the time. The band took inspiration from what North American artists like David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, and Neil Young were doing with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, one of Charly García's musical/choral models since his high school musician days.[80]

In May, PorSuiGieco began their group activities with a concert at the Auditorio Kraft, located on calle Florida.[74][80] In July 1974, they went on a tour through the province of Buenos Aires, performing in Bahía Blanca, Tandil, and Mar del Plata.[81] On July 5, 1975, they returned to perform in Tandil.[74]

In 1976, after Sui Generis had disbanded and following several delays and issues, they recorded an album under the group's name, PorSuiGieco. The album suffered from the pressure of self-censorship imposed by the actions of the Alianza Anticomunista Argentina (Triple A) and the coup groups preparing to overthrow the constitutional government. It had to be released without the track "El fantasma de Canterville", which was nonetheless included unannounced in the inner sleeve. Years later, in 2002, a CD reissue of the album would set things right. The original acoustic folk proposal evolved into a more electric and sophisticated style, though without losing the freshness that characterized the group.[82]

On March 24, 1976, a civic-military dictatorship took power, imposing a regime of state terrorism, with clandestine detention centers and task forces, responsible for kidnappings, assassinations, forced disappearances, rapes, confiscations, baby thefts, identity thefts, and forcing thousands into exile. Argentina was entering its darkest hour, with external debt, extremely high inflation, and mass impoverishment from which it would not recover in the following decades.

Sui Géneris was already a thing of the past, and Charly had begun to explore other musical paths. At the same time, he started going to a psychoanalyst as he continued to feel very anguished. He spent all day locked in his apartment, playing and composing, virtually without speaking to anyone.

1976-1977: La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros

[edit]After recording the album PorSuiGieco, García's next project was La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros (a name taken from a comic strip by Argentine cartoonist Crist), with Carlos Cutaia (keyboards), Gustavo Bazterrica (guitar and backing vocals), José Luis Fernández (bass and backing vocals), and Oscar Moro (drums and percussion).

La Máquina was Argentina's most complex and profound attempt at symphonic rock, in which García introduced the novelty of two simultaneous keyboard players. This band was one of the most meticulously crafted Argentine bands in terms of sound, but it was not well received by critics and the public.

The dictatorship established on March 24, 1976, had created a regime of terror in which no one was safe. Charly lived in fear and went out as little as possible, believing that his name could appear on the blacklists at any moment.

They debuted in Cosquín, where they premiered some of the songs that would later compose the album bearing the same name as the band. For several months, from Thursday to Sunday, they performed at La Bola Loca, Atilio Stampone's club, which hosted more than two hundred people each night to see them play live.

In July 1976, María Rosa became pregnant and gave birth to Miguel Ángel García in March 1977. Despite the arrival of the baby, the marriage was not going well. Charly García was deeply involved in his projects, focusing solely on his music, and María Rosa felt alone. A few months later, they decided to separate. It wasn't long before María Rosa found new companionship: none other than Nito Mestre, Charly's best friend.

During that winter, La Máquina gathered in a basement that flooded whenever it rained, to shape a second album: Películas. At the time, they had a peculiar record; their first album had been the most expensive in Argentine history, costing more than double the production of a common album.[citation needed]

In 1977, García attended an interview with the newspaper La Opinión, which brought together Argentine personalities from various genres. There, García was accused of making "foreignizing" music "that had nothing to do with the national sentiment", apart from lacking "the quality of the old tangos" and that "in 20 years, no one would remember him". This experience would inspire García to compose "Los sobrevivientes" and "A los jóvenes de ayer".

The Festival del Amor marked the last performance of La Máquina, at a packed Luna Park, on November 11, 1977, where they shared the stage with Nito Mestre, León Gieco, Raúl Porchetto, Gustavo Santaolalla, the Makaroff Brothers, among others.[83] García struggled to adjust to this new life as a father, distant from María Rosa. During this difficult time, he met Marisa Zoca Pederneiras, a Brazilian dancer from Oscar Araiz's ballet. Zoca would be his partner until the late 1980s and inspired several of his songs, such as "Zocacola" and "Ella adivinó".

Serú Girán (1978–1982)

[edit]In São Paulo, Charly García, amidst escalating tensions with the younger members of La Máquina, particularly due to his stage behavior, decided to leave the band in 1977. He traveled to Brazil with his friend David Lebón, a fellow musician from the era of Sui Géneris. With the money they had earned at the Festival del Amor (Luna Park, November 11, 1977), they rented a house for three months in Búzios, north of Rio de Janeiro. This choice was driven by Charly's need to be close to his girlfriend Zoca Pederneira and to escape the repressive military dictatorship in Argentina.

In São Paulo, Charly met Zoca's parents, the Pederneiras, an artistic family who were captivated by his talent. Artistically, Charly was influenced by Brazilian musicians, especially Milton Nascimento. Despite the commercial success of Sui Generis, Charly was nearly destitute. By 1978, he was living a nature-focused life with Zoca in Brazil, fishing and gathering fruit. With a new musical partner, Charly began playing again, planting the seed for a new musical project. He was determined to form a new band, despite financial challenges. Upon returning to Buenos Aires, he began searching for bandmates.

Charly needed a bass player and a drummer. He found them during a live performance by the backing band of the rock duo Pastoral. There, he recruited a talented 19-year-old bass player, Pedro Aznar, and his former colleague from La Máquina, drummer Oscar Moro. The new band was composed of Charly García (vocals, keyboards), David Lebón (vocals, guitars), Pedro Aznar (bass, vocals), and Oscar Moro (drums). Charly and David were the principal songwriters.

In 1978, Billy Bond met García and Lebón in São Paulo as they were shaping Serú Girán. Bond produced their eponymous album but made them sign an exploitative contract. Unsatisfied, Bond used some tracks recorded by the band that were discarded for the Serú Girán album, added his voice over them, and used them for Billy Bond and the Jets, a largely unnoticed 1979 album. This album contained "Loco (no te sobra una moneda)", the ironic disco song "Discoshock" (both by García), and a new funky version of "Treinta y dos macetas" from David Lebón's celebrated solo album, renamed "Toda la gente". After this formation was disbanded, Serú Girán was officially formed, with virtuoso melodies and lyrics that depicted the situation under the Argentine dictatorship. The band's popularity was also reflected in the traditional surveys of the magazine Pelo. Serú Girán won several categories from 1978 to 1981, including best guitarist, keyboardist, bassist, drummer, composer (García), and live group. Additional awards included revelation group of 1978; best singer (Lebón) in 1980 and 1981; best song in 1978 ("Seminare"), and in 1981 ("Peperina"); and best album in 1978 (Serú Giran).

Despite returning to Buenos Aires with high expectations for Charly García's new project, the beginnings were difficult. It was 1978, and the first album did not convince a skeptical public. The band's first concert was poorly received, as the audience expected a new incarnation of Sui Generis. Serú Girán represented a complete departure, featuring a new sound where Aznar's fretless bass guitar was central, and lyrics full of poetry and striking aesthetics. The audience actively requested Sui Generis' old songs. In response to the prevailing Disco music trend in Argentina in 1978, Serú Girán played a song called Disco Shock as a joke, further alienating the audience and marred the show.

The specialized press the next day dubbed Serú Girán "the worst band" in Argentina and accused David Lebón's vocals of sounding "homosexual". This led to a strained relationship with the media. A popular Argentine magazine, Gente, published a disparaging article titled "Charly García: ¿Ídolo o qué?" ("Idol or what?"). Despite the cold reception, the members of Serú Girán were convinced they had a strong project and continued to organize more shows, gradually winning acceptance from an audience that warmed up to their style.

Serú Girán's evolution continued in 1979. Their new LP, La grasa de las capitales ("Grease of The Capitals" or "The Fat of The Capitals"), featured a cover that mocked the magazine Gente. The album's direct and strong lyrics, which criticized the media (especially magazines like Gente), fashionable music, and radio, nearly resulted in the band's imprisonment. However, the album was enthusiastically received by the public. The band's performances improved, eventually being held in larger venues. The specialized press changed its attitude, and a romance developed between the people and Serú Girán.

In 1980, expectations were high for Serú Girán's new album Bicicleta ("Bicycle") – a name that Charly had originally favored for the band but was rejected by the other members. The band's sound on this record was more mature, with modern and strong music marked by prominent melodies. Pedro Aznar's bass guitar played a central role.

During Argentina's last military dictatorship (1976—1983), Charly almost faced imprisonment in 1979 due to the band's lyrics, which were considered too clear and direct. The political message in their songs became stronger yet concealed to avoid censorship and further confrontations with the military junta. However, the general message of protest remained discernible. The classic single "Canción de Alicia en el país" ("Song of Alice in The Country") drew a clever analogy between Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland and the Argentine dictatorship. "Encuentro con el diablo" ("A Meeting with the Devil") referenced the band's encounter with Interior minister Albano Harguindeguy, informally known as "the Devil". Harguindeguy had conversations with some artists at the time, ordering them to tone down their work or threatening them with leaving the country, assassination, or forced disappearance.

Serú Girán's commercial success grew, earning them the title of "The Argentine Beatles". Charly began to receive recognition as a great artist. The band was the first popular rock group to attract a following among both the rich and the poor/working class, breaking rock music out of its historically marginal position. David Lebón later reflected, "Actually, we were much more like Procol Harum than The Beatles, a legendary band: a rock 'viola' (slang for guitar) player (Lebón), a classical pianist (García), an infernal percussionist (Moro) and a virtuoso bass player (Aznar)."

Luis Alberto Spinetta, another Argentine rock star of the time, would eventually cross paths with Serú. Spinetta's first band, Almendra, was one of the first in Argentine rock, predating Sui Generis. By the late 1970s, Spinetta had formed a jazz fusion/jazz rock band called Spinetta Jade. Spinetta Jade's darker and more complex style of music was harder for general audiences to understand at the time, making Spinetta a less popular star than Charly. Nevertheless, Spinetta and Charly dispelled the myth of their rivalry on September 13, 1980, when both their bands, Serú Girán and Spinetta Jade, played together for the first time.

Patricia Perea, an 18-year-old student and correspondent for the magazine El Expreso Imaginario, covered a concert of Serú Girán and strongly criticized them after their performance in Córdoba, claiming their shows in the interior were inferior to those in the Capital Federal. Serú Girán responded to this criticism through their fourth LP, Peperina, which was named after Perea's nickname and included a song about her. The title Peperina also referred to the practice in Córdoba Province of mixing yerba mate with the herb menta peperina (Bystropogon mollis, similar to peppermint), used as a tea. This album carried a political message, with the song "José Mercado" being a clear parody of José Martínez de Hoz, Minister of Economy during the last civil-military dictatorship in Argentina. The lyrics sarcastically criticized Martínez de Hoz's tenure: "José Mercado compra todo importado (...)/José es licenciado en Economía, pasa la vida comprando porquerías" ("Market Joe only buys imported stuff (...)/Joe has a degree in Economics/And spends his life buying garbage"), targeting Argentina's then-recent policy of economic neoliberalism.

One of the songs on Peperina, titled "Llorando en el espejo" ("Crying in The Mirror"), contained the famous verse: "La línea blanca se terminó/no hay señales en tus ojos y estoy/llorando en el espejo..." ("The white line is up/there are no signs in your eyes/and I'm crying in the mirror..."), portraying cocaine addiction in clear terms. At the time, these lyrics did not attract much attention from military censors.

In early 1982, Pedro Aznar left the band to study at Boston's Berklee College of Music. Contrary to common belief, Aznar joined Pat Metheny's band a full year later, in 1983. In March 1982, Serú returned to Obras Sanitarias to bid farewell to Pedro with a highly successful show, which was recorded and released that year as No llores por mí, Argentina ("Don't cry for me, Argentina"). The loss of Aznar led to the band's dissolution, as both Lebón and Charly were ready to pursue solo careers.

In 2019, the surviving members of Serú Girán, including Pedro Aznar and David Lebón, announced the remastering of the album La grasa de las capitales. This announcement marked a significant moment in the legacy of Serú Girán.[84][85]

Second Period - Solo career

[edit]Early solo success (1982–1985)

[edit]In 1982, Argentina was undergoing political change. After the Falklands War (Spanish: Guerra de las Malvinas/Guerra del Atlántico Sur) in June, social chaos erupted and the military government lost part of its power.

Charly García debuted as a soloist with a double LP, Pubis Angelical ("Angelical Pubis"), which was the eponymous movie's soundtrack, and the powerful Yendo de la cama al living ("Going from the bed to the living room"). Four hit songs from this album left their historical mark:

- "No bombardeen Buenos Aires" ("Don't bomb Buenos Aires") showed the panic in lived out in the city during the Falklands War, and strongly criticized Argentina's last civil-military dictatorship (1976–1983), especially then ruling dictator Leopoldo Galtieri (Roger Waters from Pink Floyd, on the other side of the trenches at that time, also criticized Galtieri in their 1983 Final Cut album).

- "Yendo de la cama al living" ("Going from the bed to the living room") used the experience of being trapped in a confined space as a symbol of the repression of ideas.

- "Inconsciente colectivo" ("Collective unconscious") was a message of hope and liberty for the stricken Argentine people.

- "Yo no quiero volverme tan loco" ("I don't want to go so crazy") was a song about the adolescent spirit of freedom and rebelliousness.

The LP's presentation took place in December at the Ferrocarril Oeste Stadium (or Ferro). As the song "No bombardeen Buenos Aires" drew to a close near the end of the show, backdrop props simulating Buenos Aires were destroyed with fireworks.

In 1983, Charly left Buenos Aires with a small suitcase. When he returned to Buenos Aires from New York, he brought a quality LP titled Clics Modernos ("Modern Clicks") that was different from anything previously done in Argentine rock – it was highly singable rock music you could also dance to. Its strong message referred the past years: Exodus in "Plateado sobre plateado (huellas en el mar)" ("Silver on Silver, Footprints on the Sea"), repression in "Nos siguen pegando abajo" ("They keep hitting us down there"), "No me dejan salir" ("They won't let me out") and "Los dinosaurios" ("The Dinosaurs"), a nostalgic but defiant remembrance of those who were kidnapped, tortured, or killed.

On December 10, the course of Argentine history took a turn as the government became a democracy. Charly performed many well-received shows in 1984, and recorded another album during its last months. García also recorded an LP called Terapia intensiva ("Intensive care"), another movie soundtrack. One of Charly's shows that year took place in an underground bar, with his new group named "Giovanni y los de Plástico" ("Giovanni and the Plastic Ones"). Piano Bar was released in 1984, completing García's golden trilogy.

During these years, García's band was home to many future Argentine music stars, including Andrés Calamaro, Fito Páez, Pablo Guyot, Willy Iturri, Alfredo Toth and Fabiana Cantilo.

Massive stardom and classic albums (1985–1989)

[edit]After the success of Piano Bar, which was García's consecration as a soloist, 1985 was a year to slow down. Charly met again with Pedro Aznar in New York by chance, but they took advantage of this meeting and recorded Tango. The record had some interesting material, but it did not achieve commercial success primarily due to limited distribution.

In 1987, García came back with Parte de la Religión ("Part of the Religion"), a very interesting LP. Many songs from that LP became hits. Two of them, "No voy en tren" ("I don't take the train") and "Necesito tu amor" ("I need your love") are the perfect symbol of García's dichotomies: the first one says "No necesito a nadie a nadie alrededor" ("I don't need anybody around me"), and the second one says "Yo necesito tu amor/tu amor me salva y me sirve" ("I need your love/your love saves me and is useful to me"). This LP is also featured a song, "Rezo por vos" ("I pray for you"), which was part of a project with Luis Alberto Spinetta that was never finished.

In 1988, Charly made his acting debut at the age of 36, playing a nurse in the movie Lo que vendrá ("What is to come"), the soundtrack of which he also composed. Being a nurse had long been one of García's obsessions. Later that year, the Amnesty International festival wrapped up in Buenos Aires. Starring international and local rock stars, Peter Gabriel, Bruce Springsteen, Sting, Charly García and León Gieco were there.

In 1989, Puerto Rican pop star Wilkins invited Charly to record his classic "Yo No Quiero Volverme Tan Loco", alongside Ilan Chester, from Venezuela, as a tribute to "Rock en Español"; the song was featured in Wilkins' L.A-N.Y. album.

Later that year, Charly released a new album, Cómo conseguir chicas ("How to get girls"). This would probably be his last "normal" album. He described it as "Just a bunch of songs that were never published for different reasons".

Charly's father had long ago told him, "Never write an anagram for someone if you don't want him or her to be pissed off". During the Serú Girán years, his friend David Lebón told him something similar: "Do not write a song for a woman if you love her, because she'll leave you". The LP includes a song titled "Shisyastawuman" (a deliberately direct transliteration of "She's just a woman"), the first song García recorded in English that was written to a woman. The woman left him after hearing the song, just like Lebón had warned. A song named "Zocacola" that Charly dedicated to Zoca was included in this LP as well. A couple of months after the record was released, Zoca left him.

García had changed. Physically, he looked older. His music was dark, and the earlier symphonical García from La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros was gone. Now, Charly's sound was closer to either punk rock, with violent songs such as "No toquen" ("Do Not Touch"), or a depressive and dark style as shown in "No me verás en el subte" ("You Won't See Me in the Subway"). Different and adverse times lay ahead.

For the international tour in 1989/1990, García formed a new band with Hilda Lizarazu, who sang backup vocals for Charly.

Days of excess (1990–1993)

[edit]In 1990, Charly had many ideas but no band. Another important member of the band, Fabián "Zorrito" Von Quintiero, had left to join another band, Los Ratones Paranoicos (The Paranoid Mice). Hilda Lizarazu was busy with her band called Man Ray. For Filosofía barata y zapatos de goma ("Cheap Philosophy and Rubber Shoes") Charly gathered many of his old friends, who helped record most of the songs. Assisting him, among others, were Andrés Calamaro, Rinaldo Rafanelli, Fabiana Cantilo, "Nito" Mestre, Pedro Aznar, Fabián Von Quintiero and even Hilda Lizarazu. The first issue came once the disc was released. Its last song was a rock version of the "Himno Nacional Argentino", or the Argentine national anthem. Amid controversy, García's version of the national anthem was forbidden for some days, but García was victorious, a judge authorizing the song.

That year, the Government of Buenos Aires organized Mi Buenos Aires Rock (My B.A. rock), a public rock festival on Avenue 9 de Julio, the city's most famous avenue. Every act was scheduled to play 30 minutes, but Charly played for over two hours. He closed the festival playing his version of the national anthem to one hundred thousand people.

In December 1992, Charly again embraced his past and surprisingly re-formed Serú Girán. Charly García, David Lebón, Pedro Aznar and Oscar Moro were back after ten years. A new album was recorded, titled Serú 92. It enjoyed great commercial success, but musically was sharply different from Serú Girán's other records.

Serú Girán performed two sold-out shows at the Estadio Monumental Antonio Vespucio Liberti, the largest in Argentina. Serú Girán had always been at its best when live, the four members playing very well together. This time, in Moro's words, "the show sounded like Charly García and Serú Girán".

Say No More era (1994–2000)

[edit]After not having released any new solo material since 1990, in 1994 García was ready to strike back. The new project was called La hija de "La Lágrima" ("The Tear's Daughter"). This LP would be an introduction to the future concept of Say No More.

Also during 1994, the Soccer World Cup was being played in the United States. Soccer player legend Diego Armando Maradona was involved in a dispute with FIFA regarding a drug test for ephedrine doping, which he failed, preventing him from playing. After Diego was sent home, Argentina lost two important matches and was knocked out of the World Cup. When the last match was about to end, Charly called Diego on his cell phone and sang to him "live" the Maradona's Blues, a song he composed for him. Diego cried when he heard "Un accidente no es pecado/y no es pecado estar así" ("An accident is not a sin/And is not a sin to be like this"), and the two struck up a friendship.

1995 was again a musical year. García formed a new band for touring on summertime (with María Gabriela Epumer, Juan Bellia, Fabián Von Quintiero, Jorge Suárez and Fernando Samalea) and named it as "Casandra Lange". His idea with the band was to play songs Charly had heard as a teen, such as "Sympathy for the Devil" (Mick Jagger–Keith Richards) and "There's a Place" (John Lennon–Paul McCartney). He recorded the performances and edit a live album, Estaba en llamas cuando me acosté ("I was on fire when went to bed"). All of the songs in this album are in English except for "Te recuerdo invierno" ("I remember you, winter"), which García had written in the early 1970s but never recorded with Sui Generis. In May, Charly recorded Hello! MTV Unplugged, which is often considered by music critics as the last time that the rock star played his music to his full potential.

Say No More arrived in 1996. Say No More was a new concept for García: "'Say No More' would be in music what painting directly on the canvas would be for a painter", he explained. He also said that the LP "will only be understood in 20 years". Today the album is considered García's masterpiece, and "Say no more" the classic slogan identifying Charly García and all his music.[citation needed]

During 1997, García recorded Alta Fidelidad ("High Fidelity") with Mercedes Sosa. Both had known each other since his childhood, so they decided to publish a collaborative work on which Mercedes would sing her favorite García songs of all time.

In 1998, El aguante ("Holding On") was released. This production featured many covers translated to Spanish by García, like "Tin Soldier" (Small Faces), or "Roll over Beethoven" (Chuck Berry). A significant song which was not included was "A Whiter Shade of Pale" by Procol Harum, a band that Charly has admittedly always admired.

In February 1999, García performed at the closing of the free public-rock festival "Buenos Aires Vivo III" (BA Live III). There he played a huge concert for 250.000 fans who attended one of the biggest concerts in Argentina up to that date. In July 1999, Charly agreed to give a private performance on Quinta de Olivos (the Argentine Presidential residence), at the request of the president, Carlos Saúl Menem. On a televised bit of this event he was seen in good spirits, carrying out antics such as playing with the security cameras, or trying to teach the president how to play the piano. A limited edition of a disc memorializing the famous concert, Charly & Charly, was released that year. Since its release, Charly & Charly has been out of print, and is currently available only in bootleg copies on Internet sites.

Maravillización (2000–2003)

[edit]In 2000, Charly and Nito Mestre decided to bring Sui Generis back to life. For the special occasion, they both composed the songs for a new LP, "Sinfonías para adolescentes" ("Symphonies for Adolescents"). This new period would be marked by García's new "sound concept" of Maravillización or "Making something marvellous", replacing the old dark "Say no more" style.

Finally Sui Generis played again in the Boca Juniors's Stadium, for 25,000 fans on December 7, 2000. Charly played for almost four hours.

Many journalists criticized this return, stating that the main cause for it was the money and that both members of the band had changed so much, that the new album and show had nothing to do with the "real" Sui Generis.

During 2001, ¡Si! Detrás de las paredes ("B [the musical note]! Behind the Walls") was edited as the second and last Sui Generis's LP in this new era. It was a mash up between live versions of the Boca Juniors's concert, new songs (as "Telepáticamente") and some versions of old songs. (such as "Rasguña Las Piedras", featuring Gustavo Cerati, former leader of Soda Stereo). Besides on October 23, 2001, Charly reached age 50. For the occasion, a special concert in the Colliseum Theater was organized.

After this interruption in his solo Career, Charly got back to the spotlight after releasing Influencia ("Influence") in 2002. This new disc contained some interesting songs that made an impact in the Latin American world of Rock, such as "Tu Vicio" ("Your Vice"), "Influencia" ("Influence", translated cover from Todd Rundgren's original "Influenza") and "I'm Not In Love" (featuring Tony Sheridan). Even though it included old songs as "Happy And Real" (from Tango IV, 1991) or "Uno A Uno" ("One to one", from El Aguante, 1998) and different versions of the same songs, this was probably García's best album since 1994.

Live concerts of Influencia were probably Charly's best in a long, long time. With the strong support of María Gabriela Epumer in chorus and guitar, Charly showed up in many different concerts, such as two in the Luna Park Stadium, Viña del Mar and Cosquín Rock with correct performances.

Finally in October 2003, Charly released Rock and Roll, Yo ("Rock and Roll, Me"), dedicated to María Gabriela. The songs weren't as good as those in Influencia, his voice often sounds out of tune and, once again the LP contained too many versions and translated covers such as "Linda Bailarina" ("Pretty Ballerina", Michael Brown) or "Wonder" ("Love´S in Need of Love Today" by Stevie Wonder).

Drop into the background (2004–2008)

[edit]In 2004 García achieved one of his most remarkable and positive landmarks of that era: he played for the second time in Casa Rosada, the Argentine Government Palace. This event took place during the presidency of Néstor Kirchner. On April 30, 2007, Charly performed in the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires at the invitation of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo Human Rights' Organization, commemorating their 30th Anniversary. Also around that time García routinely performed throughout Argentina and South America.

On June 14, 2008, the Clarín newspaper reported that Charly García was taken to a hospital in the city of Mendoza due to a violent episode in which the musician thrashed a hotel room in Mendoza. Sources related the incident to an overdose of drugs and alcohol.[86] After the incident García's friend, the singer and former politician Palito Ortega, took Charly to his country estate in Buenos Aires Province, where Ortega helped him to begin a treatment with several doctors and psychiatrists to cure his addiction. The recovery process took almost an entire year.

Third Period - Comeback and status as a living legend (2009-present)

[edit]Recovery, new material

[edit]After a year-long recovery living in Ortega's estate, a cured and stable Charly came back in August 2009 with a new song called "Deberías Saber Por qué" (You Should Know Why). The song became a hit and soon Charly embarked on a large tour through Chile and Perú to promote his return. On October 23 García celebrated his 58th birthday with a concert in Velez Sarfield's Stadium, Argentina. This concert has been referred to as "The Underwater Concert" because of the heavy rain that fell that night.

In October 2011, Charly was the last guest on Susana Giménez' TV show's final episode. While appearing on the show, he performed the song "Desarma y Sangra", originally from his band Serú Girán.

In September 2013, Charly performed in an exclusive show called "Líneas Paralelas, Artificio imposible" (Parallel Lines, Impossible Craft) at Teatro Colón, along with two string quartets (baptized "Kashmir Orchestra" in homage to the band Led Zeppelin) and his bandmates "The Prostitution". At the venue, they made classical arrangements to Charly's own songs under his own musical direction.[87] Charly then traveled to Mendoza City to present various compositions made across his life, specially the ones he created since the 2000s.

Random

[edit]In 2016 Charly had several health problems and appeared to walk in and out of clinics and medical controls. On February 24, 2017, after months of speculation about Charly's health, he surprisingly announced the release of his new studio album, Random, his first studio album in seven years, which is entirely made of new original compositions. Since its release, the album has received mostly positive reviews and important record sales.

On April 19, 2017, Charly accused Bruno Mars and Mark Ronson of plagiarism, stating that their song "Uptown Funk" stole the initial chords and riff of his classic song "Fanky", from Cómo conseguir chicas (1989).[88]

Recent years

[edit]

In October 2021 Argentina's government organized a special event to celebrate Charly García's 70th birthday. In a historic and emotional day, the Kirchner Cultural Centre (CCK) (part of the Ministry of Culture), celebrated García's birthday with live music, a series of talks/lectures and performances. A series of live concerts were held at the CCK, where several of Argentina's most important musicians covered García's classic repertoire. Charly himself made a surprise appearance and performed for the cheering crowd.[89]

Discography

[edit]- 1972: Vida

- 1973: Confesiones de Invierno

- 1974: Pequeñas anécdotas sobre las instituciones

- 1975: Alto en la Torre (EP)

- 1975: Ha Sido (unreleased)

- 1975: Adiós Sui Géneris I & II

- 1996: Adiós Sui Géneris III

- 2000: Sinfonías para adolescentes

- 2001: Si - Detrás de las Paredes

- 1976: Porsuigieco

- 1976: La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros

- 1977: Películas

- 1978: Billy Bond and The Jets

- With Serú Girán

- 1978: Serú Girán

- 1979: La Grasa de las Capitales

- 1980: Bicicleta

- 1981: Peperina

- 1982: No llores por mí, Argentina

- 1992: Serú '92

- 1993: En Vivo I & II

- 2000: Yo no quiero volverme tan loco

- Other Collaborations

- 1980: Música del alma

- 1999: Charly & Charly

- Solo

- 1982: Pubis Angelical/Yendo de la Cama al Living

- 1983: Clics modernos

- 1984: Piano Bar

- 1987: Parte de la Religión

- 1989: Cómo Conseguir Chicas

- 1990: Filosofía Barata y Zapatos de Goma

- 1994: La Hija de la Lágrima

- 1995: Estaba en llamas cuando me acosté

- 1995: Hello! MTV Unplugged

- 1996: Say No More

- 1998: El Aguante

- 1999: Demasiado ego

- 2002: Influencia

- 2003: Rock and Roll Yo

- 2010: Kill Gil

- 2017: Random

- 2024: La lógica del escorpión

- With Pedro Aznar

- 1986: Tango

- 1991: Radio Pinti (with Enrique Pinti)

- 1991: Tango 4

- With Mercedes Sosa

- 1997: Alta fidelidad

Bibliography

[edit]- Favoretto, Mara (2013). Charly en el país de las alegorías. Un viaje por las letras de Charly García. Buenos Aires: Gourmet Musical. p. 192.

- Di Pietro, Roque (2020). Esta noche toca Charly. Un viaje por los recitales de Charly García (1956-1993). Buenos Aires: Gourmet Musical.

- Di Pietro, Roque (2021). Esta noche toca Charly. Un viaje por los recitales de Charly García. Tomo 2: Say No More (1994-2008). Buenos Aires: Gourmet Musical.

- Marchi, Sergio (1997). No digas nada. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana.

References

[edit]- ^ "Charly García | Biography, Albums, Streaming Links". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ DPA (June 19, 2017). "Las diez principales figuras del medio siglo del rock argentino". Prensa Libre. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

Gustavo Cerati... Desde la admiración que tenía por García y Spinetta se convirtió en el único músico capaz de disputarles la categoría de máximos referentes...

- ^ Pareles, Jon (April 27, 2012). "A Mannequin for a Beat, Buñuel for Intermission". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 15, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Argentine Rock Icon Charly Garcia Breaks Silence on 'Random': Interview". Billboard. Estados Unidos. June 7, 2007. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ Seitz, Maximiliano (March 9, 2007). "Charly García: rebelde busca la inocencia". BBC. Archived from the original on June 11, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ "Las diez principales figuras del medio siglo del rock argentino". Prensa Libre. June 19, 2017. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

Gustavo Cerati... Desde la admiración que tenía por García y Spinetta se convirtió en el único músico capaz de disputarles la categoría de máximos referentes...

- ^ Pareles, Jon (April 27, 2012). "A Mannequin for a Beat, Buñuel for Intermission". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 15, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Argentine Rock Icon Charly Garcia Breaks Silence on 'Random': Interview". Billboard. June 7, 2007. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ Cavalcanti, Tatiana (December 27, 2018). "Musico argentino Charly Garcia tera sua historia retratada em musical que-estreia em SP em 2020". Uol (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ Seitz, Maximiliano (March 9, 2007). "Charly García: rebelde busca la inocencia". BBC. Archived from the original on June 11, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ "Los 100 Mejores Discos del Rock Nacional". Rate Your Music. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2023.