Gottfried von Cramm

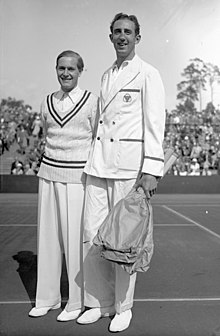

Gottfried von Cramm (left) and George Lyttleton Rogers of Ireland in 1932 | |

| Full name | Gottfried Alexander Maximilian Walter Kurt Freiherr von Cramm |

|---|---|

| Country (sports) | |

| Born | 7 July 1909 Nettlingen, German Empire |

| Died | 8 November 1976 (aged 67) Cairo, Egypt |

| Height | 1.83 m (6 ft 0 in) |

| Turned pro | 1931 (amateur tour) |

| Retired | 1952 |

| Plays | Right-handed (one-handed backhand) |

| Int. Tennis HoF | 1977 (member page) |

| Singles | |

| Career record | 390–82 (82.6%)[1] |

| Career titles | 45[1] |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (1937, ITHF)[2][3] |

| Grand Slam singles results | |

| Australian Open | SF (1938) |

| French Open | W (1934, 1936) |

| Wimbledon | F (1935, 1936, 1937) |

| US Open | F (1937) |

| Doubles | |

| Grand Slam doubles results | |

| Australian Open | F (1938) |

| French Open | W (1937) |

| Wimbledon | SF (1933, 1937) |

| US Open | W (1937) |

| Grand Slam mixed doubles results | |

| Wimbledon | W (1933) |

Gottfried Alexander Maximilian Walter Kurt Freiherr[A][4] von Cramm (German: [ˈɡɔtfʁiːt fɔn ˈkʁam] ; 7 July 1909 – 8 November 1976) was a German tennis player who won the French Championships twice and reached the final of a Grand Slam singles tournament on five other occasions. He was ranked number 2 in the world in 1934 and 1936, and number 1 in the world in 1937.[2][5][6] He was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1977, which states that he is "most remembered for a gallant effort in defeat against Don Budge in the 1937 Interzone Final at Wimbledon".[3]

Von Cramm had difficulties with the Nazi regime, which attempted to exploit his appearance and skill as a symbol of Aryan supremacy, but he refused to identify with Nazism. Subsequently he was persecuted as a homosexual by the German government and was jailed briefly in 1938.

Von Cramm figured briefly in the gossip columns as the sixth husband of Barbara Hutton, the Woolworth heiress.

Birth and childhood

[edit]

Third of the seven sons of Baron Burchard von Cramm (1874-1936), by his marriage to Countess Jutta von Steinberg (1888–1972), Cramm was born at the family estate, Castle Nettlingen, Lower Saxony, Germany and grew up in Castle Brüggen which also belonged to his family. A younger brother, Wilhelm-Ernst Freiherr von Cramm (1917–1996), was a German officer who was highly decorated during the Second World War, and who after the war was leader of the German Party, a conservative German political party. Through the mutual ancestry from the Cramm family, he was third cousin of Bernhard, Prince of the Netherlands.[7]

Von Cramm began playing tennis around the age of ten after his right hand had recovered from an accident. That accident, which resulted in him losing the top joint of his index finger on his right hand, was the result of a horse who took more than just the sugar cube offered to him by the young von Cramm.[8]

Tennis career

[edit]In 1932, Cramm earned a place in the German Davis Cup team and won the first of four straight German national tennis championships.[9] During this time he also teamed up with Hilde Krahwinkel to win the 1933 mixed doubles title at Wimbledon. Noted for his gentlemanly conduct and fair play, he gained the admiration and respect of his fellow tennis players. He earned his first individual Grand Slam title in 1934, winning the French Open. His victory made him a national hero in his native Germany; however, it was by chance that he won just after Adolf Hitler had come to power. The handsome, blond Gottfried von Cramm fitted perfectly the Aryan race image of a Nazi ideology that put pressure on all German athletes to be superior. However, Cramm steadfastly refused to be a tool for Nazi propaganda. Germany effectively lost its 1935 Davis Cup Interzone Final against the US when Cramm refused to take a match point in the deciding game, by notifying the umpire that the ball had tipped his racket, and thus calling a point against himself, although no one had witnessed the error.[10]

For three straight years Cramm was the men's singles runner-up at the Wimbledon Championships, losing in the final to England's Fred Perry in 1935 and again in 1936. The following year he was runner-up to American Don Budge, both at Wimbledon and at the U.S. Open. In 1935, he was beaten in the French Open final by Perry, but turned the tables the following year and defeated his rival, gaining his second French championship.

In addition to his Grand Slam play, Gottfried von Cramm is recalled for his deciding match against Don Budge during the 1937 Davis Cup. He was ahead 4–1 in the final set when Budge launched a comeback, eventually winning 8–6 in a match considered by many as the greatest battle in the annals of Davis Cup play and one of the pre-eminent matches in all of tennis history.[3] In a later interview, Budge said that Cramm had received a phone call from Hitler minutes before the match started and had come out pale and serious and had played each point as though his life depended on winning.[11] Ted Tinling, who served as the Player Liaison for the All England Club, recalled in his memoir that as he was in the process of ushering Budge and von Cramm out to Centre Court, they were interrupted by a long-distance call for von Cramm, and that following the call, von Cramm turned to him and Budge and said, 'Excuse me, gentlemen, it was Hitler. He wanted to wish me good luck.'[12] Others say that Budge believed a tale invented by Teddy Tinling that Hitler had telephoned Cramm before the match.[13]

For his successful tennis career, he was decorated by the President of the Federal Republic of Germany with the Silver Laurel Leaf, Germany's highest sports award.[14]

Imprisonment for same-sex affair

[edit]Despite his enormous popularity with the public, on 5 March 1938, von Cramm was arrested by the German government and tried on the charge of a homosexual relationship with Manasse Herbst, a young Galician Jewish actor and singer, who had appeared in the 1926 silent film Der Sohn des Hannibal.[15] After being hospitalized for a nervous collapse after his arrest, on 14 March von Cramm was sentenced to one year's imprisonment[16] Cramm admitted the relationship, which had lasted from 1931 until 1934 and had begun shortly before he married his first wife. He was additionally charged with sending money to Herbst, who had moved to Palestine in 1936. According to a report on the trial in The New York Times of 15 May 1938, the judge stated that "Baron von Cramm had alleged that his wife, during their honeymoon, had become intimate with a French athlete. The court held that this experience had unsettled the young tennis star and had resulted in his seeking a perverse compensation for an unhappy married life."[17] Although Cramm had confessed to an affair with Herbst once he was arrested, he later changed his confession to one of "mutual masturbation", and his lawyer was able to convince the judge that Cramm had been forced into sending money to Herbst because Herbst was a "sneaky Jew".[18]

Cramm's international tennis friends were outraged at his treatment. Don Budge collected the signatures of high-profile athletes and sent a protest letter to Hitler. His friend King Gustaf V of Sweden also pressured the German government to have him released. Cramm was released on parole after six months,[15] and in May 1939 returned to competitive tennis. Cramm competed at the Queen's Club Championships in London, where he won the event by beating American Bobby Riggs 6–0, 6–1. Officials at Wimbledon reportedly refused to let him play in their tournament, using the excuse that he was a convicted criminal and therefore unfit; The New York Times, however, quoted Wimbledon sources as saying that Cramm would have been welcome to participate, had he submitted an entry.[citation needed]

A further humiliation was Germany's decision in 1940 to recall Cramm from an international tennis tournament in Rome before he had a chance to play.

Connections to the German resistance

[edit]Cramm refused to become a party member of the NSDAP during the entire period of the National Socialist regime, although Hermann Göring, who was a member of the same tennis club, tried to persuade him several times. Because Cramm never mentioned Hitler during speeches on international trips, watched films critical of the regime, and privately spoke disparagingly of the National Socialists, he increasingly aroused the displeasure of the Nazis.

Von Cramm showed solidarity with the active resistance to Hitler in the last years of the war, using his travels as a tennis coach to Sweden to pass on confidential messages from the 20 July conspirators.[19] After the failed assassination attempt, he expressed his desire to join another attempt.[20] Since the resistance never reorganised after the 20 July plot, he never got the chance to turn his words into deeds.

Wartime service and postwar career

[edit]In May 1940, some months after the outbreak of the Second World War, Cramm was conscripted into military service[15] as a member of the Hermann Goering Division.[21] He saw action on the Eastern Front and was awarded the Iron Cross.[4] Despite his noble background, Cramm was enlisted as a private soldier until being given a company to command. His company faced harsh conditions on the Eastern Front, and Cramm was flown out suffering from frostbite, with much of his company dead. Because of his previous conviction, he was dismissed from military service in 1942.[15]

While the war robbed Cramm of some of his best years as a tennis player, he won the German national championship in 1948 and again in 1949, when he was 40 years old. He went on playing Davis Cup tennis until retiring after the 1953 season and still holds the record for the most wins by any German team member.

Following his retirement from active competition, Cramm served as an administrator in the German Tennis Federation. He was instrumental in reviving the Lawn Tennis Club Rot-Weiss in Berlin following World War II, and later served as its Chairman and President (1958-death).[22] Von Cramm became successful in business as a cotton importer. In addition, he managed the landed estate he had inherited from his father in Wispenstein, in Lower Saxony.

Marriages

[edit]Gottfried von Cramm married:

- Baroness Elisabeth Lisa von Dobeneck (1912–1975), a daughter of Robert, Baron von Dobeneck (died in 1926) and his wife, the former Maria Hagen (1889–1943), a granddaughter of the Jewish banker Louis Hagen.[23] They married on 1 September 1930 and divorced in 1937.[24] Lisa von Cramm later married the German ice-hockey star Gustav Jaenecke.

- Barbara Hutton, an American socialite and an heiress to the Woolworth five-and-dime fortune. The couple married in 1955 and divorced in 1959. He had married her in order to "help her through substance abuse and depression but was unable to help her in the end."[18]

Death

[edit]While on a business trip, Cramm and his driver were killed in an automobile accident near Cairo, Egypt, in 1976, when the baron's car collided with a truck. Two roads were named in his honor, the Gottfried-von-Cramm-Weg in Berlin-Wilmersdorf, where the Rot-Weiss Tennis Club is located, and a similarly named road in the small town of Merzig.

Gottfried von Cramm was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1977.[3]

In his 1979 autobiography, Jack Kramer, the long-time tennis promoter and a great player, included Gottfried von Cramm in his list of the 21 greatest players of all time.[B] Cramm was the subject of a radio play, titled Playing for His Life, first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in June 2011. The play focused on the 1937 Interzone Davis Cup final and on Cramm's personal life.[25] Cramm's story is featured at some length in the 2023 Netflix documentary Eldorado – everything the Nazis hate.[26]

Grand Slam finals

[edit]Singles (2 titles, 5 runners-up)

[edit]| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Opponent | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1934 | French Championships | Clay | 6–4, 7–9, 3–6, 7–5, 6–3 | |

| Loss | 1935 | French Championships | Clay | 3–6, 6–3, 1–6, 3–6 | |

| Loss | 1935 | Wimbledon | Grass | 2–6, 4–6, 4–6 | |

| Win | 1936 | French Championship | Clay | 6–0, 2–6, 6–2, 2–6, 6–0 | |

| Loss | 1936 | Wimbledon | Grass | 1–6, 1–6, 0–6 | |

| Loss | 1937 | Wimbledon | Grass | 3–6, 4–6, 2–6 | |

| Loss | 1937 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 1–6, 9–7, 1–6, 6–3, 1–6 |

Doubles (2 titles, 1 runner-up)

[edit]| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Partner | Opponents | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1937 | French Championships | Clay | 6–4, 7–5, 3–6, 6–1 | ||

| Win | 1937 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 6–4, 7–5, 6–4 | ||

| Loss | 1938 | Australian Open | Grass | 5–7, 4–6, 0–6 |

Mixed doubles (1 title)

[edit]| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Partner | Opponents | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1933 | Wimbledon Championships | Grass | 7–5, 8–6 |

Grand Slam singles performance timeline

[edit]| W | F | SF | QF | #R | RR | Q# | DNQ | A | NH |

| Tournament | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | 1946 | 1947 | 1948 | 1949 | 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | SR | W–L | Win % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | SF | A | A | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 0 / 1 | 3–1 | 75.0 |

| France | 4R | 2R | A | W | F | W | A | A | A | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | A | A | A | A | A | A | 1R | 2 / 6 | 21–4 | 84.0 |

| Wimbledon | 4R | 2R | 3R | 4R | F | F | F | A | A | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | A | A | A | A | A | 1R | A | 0 / 8 | 27–8 | 77.1 |

| United States | A | A | A | A | A | A | F | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 0 / 1 | 5–1 | 83.3 |

Source: ITF[27]

Notes

[edit]- A Regarding personal names: Freiherr was a title before 1919, but now is regarded as part of the surname. It is translated as Baron. Before the August 1919 abolition of nobility as a legal class, titles preceded the full name when given (Graf Helmuth James von Moltke). Since 1919, these titles, along with any nobiliary prefix (von, zu, etc.), can be used, but are regarded as a dependent part of the surname, and thus come after any given names (Helmuth James Graf von Moltke). Titles and all dependent parts of surnames are ignored in alphabetical sorting. The feminine forms are Freifrau and Freiin.

- B Writing in 1979, Kramer considered the best ever to have been either Don Budge (for consistent play) or Ellsworth Vines (at the height of his game). The next four best were, chronologically, Bill Tilden, Fred Perry, Bobby Riggs and Pancho Gonzales. After these six came the "second echelon" of Rod Laver, Lew Hoad, Ken Rosewall, Gottfried von Cramm, Ted Schroeder, Jack Crawford, Pancho Segura, Frank Sedgman, Tony Trabert, John Newcombe, Arthur Ashe, Stan Smith, Björn Borg and Jimmy Connors. He felt unable to rank Henri Cochet and René Lacoste accurately but felt they were among the very best.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Garcia, Gabriel. "Gottfried Von Cramm: Career match record". thetennisbase.com. Tennismem SL. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Budge Seeded First in All-England", Daytona Beach Morning Journal, 17 June 1937.

- ^ a b c d "Baron Gottfried von Cramm". www.tennisfame.com. International Tennis Hall of Fame.

- ^ a b Ron Fimrite (5 July 1993). "Baron of the Court". Sports Illustrated. Vol. 79, no. 1. pp. 56–69.

- ^ J. Brooks Fenno, Jr. (20 October 1934). "Ten at the Top in Tennis". The Literary Digest. New York City, United States: Funk & Wagnalls: 36.

- ^ "Wallis Myers' Rankings". The Age. 24 September 1936. p. 6 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ "Relationship Calculator: Genealogics".

- ^ Merrihew, Stephen Wallis (20 February 1938). "Von Cramm's Life Story: He tells it for the Sydney Daily Telegraph and it is laid bare before the ALT Readers". American Lawn Tennis. XXXI (14): 26.

- ^ "Abschluss der Deutschen Tennis-Meisterschaften". Hamburger Nachrichten (in German). 15 August 1932 – via European Library.

- ^ Paul Fein, Tennis Confidential: Today's Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies, Brassey's, 2003 p. 144.

- ^ "Don Budge Describes his 1937 Davis Cup Semi-final Match Against Baron Gottfried von Cramm" Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tinling, Ted (1983). Sixty Years in Tennis. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. p. 113. ISBN 0-283-98963-7.

- ^ Fisher, Marshall Jon (2009). A Terrible Splendor: Three Extraordinary Men, a World Poised for War, and the Greatest Tennis Match Ever Played. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0307393951.

- ^ Sportbericht der Bundesregierung vom 29. 9. 1973 an den Bundestag - Drucksache 7/1040 - Seite 62 Verleihung des Silbernen Lorbeerblattes...

- ^ a b c d Kernchen, Roland. "Gottfried von Cramm - Weltspitzensportler und Freund Wispensteins" [Gottfried von Cramm - World-class Athlete and Friend of the Wispenstein Community]. Homepage of the Wispenstein Community (in German). Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ "People, May 23, 1938". Time. 23 May 1938. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Cramm Sentenced to a Year in Prison; He Was Blackmail Victim". The New York Times. 15 May 1938. p. 6.

- ^ a b Fisher, Marshall Jon (2009). A Terrible Splendor. New York: Crown. ISBN 9780307393944.

- ^ Fritsche, Andreas. "Harter Aufschlag 1938". nd-aktuell.de (in German). Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ "Porträt einer Tennislegende: Gottfried von Cramm: Sein Platz war die Welt". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). ISSN 1865-2263. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ "Von Cramm, German Tennis Star Of 1930's, Dies in Car Crash at 66". The New York Times. 10 November 1976.

- ^ "Der Club". LTTC Rot-Weiss. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ Fraunhofer SCAI Marketing und Kommunikation. "Fraunhofer IZB: Seite nicht gefunden". fraunhofer.de. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007.

- ^ "Sport: Champions at Forest Hills". Time. 13 September 1937. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ Playing for his life, Afternoon drama, BBC Radio 4, 24 June 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Eldorado – everything the Nazis hate". Netflix. 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ "Player profile – Gottfried von Cram". International Tennis Federation (ITF).

Further reading

[edit]- Fisher, Marshall Jon (2009). A Terrible Splendor: Three Extraordinary Men, a World Poised for War and the Greatest Tennis Match Ever Played. ISBN 978-0-307-39394-4

- Simkin, John (6 July 2018). "Why was the anti-Nazi German, Gottfried von Cramm, banned from taking part at Wimbledon in 1939?". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 23 July 2018

- Nordalm, Jens (2021). Der schöne Deutsche: Das Leben des Gottfried von Cramm (in German). Rowohlt E-Book. ISBN 978-3-644-00819-9.

External links

[edit]- Gottfried von Cramm at the International Tennis Hall of Fame

- Gottfried von Cramm at the Association of Tennis Professionals

- Gottfried von Cramm at the International Tennis Federation

- Gottfried von Cramm at the Davis Cup

- Official page Archived 19 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Newspaper clippings about Gottfried von Cramm in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1909 births

- 1976 deaths

- German barons

- Bisexual sportsmen

- French Championships (tennis) champions

- German male tennis players

- Grand Slam (tennis) champions in men's doubles

- Grand Slam (tennis) champions in men's singles

- Grand Slam (tennis) champions in mixed doubles

- International Tennis Hall of Fame inductees

- Recipients of the Silver Laurel Leaf

- German bisexual sportspeople

- German bisexual men

- LGBTQ tennis players

- People convicted under Germany's Paragraph 175

- People prosecuted under anti-homosexuality laws

- People from Hildesheim (district)

- Persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany

- Recipients of the Iron Cross (1939)

- Road incident deaths in Egypt

- United States National champions (tennis)

- West German male tennis players

- Wimbledon champions (pre-Open Era)

- Woolworth family

- Tennis players from Lower Saxony