Reticulocytosis

| Reticulocytosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reticulocyte | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

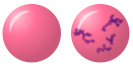

Reticulocytosis is a laboratory finding in which the number of reticulocytes (immature red blood cells) in the bloodstream is elevated. Reticulocytes account for approximately 0.5% to 2.5% of the total red blood cells in healthy adults and 2% to 6% in infants, but in reticulocytosis, this percentage rises.[1] Reticulocytes are produced in the bone marrow and then released into the bloodstream, where they mature into fully developed red blood cells between 1-2 days.[2] Reticulocytosis often reflects the body’s response to conditions rather than an independent disease process and can arise from a variety of causes such as blood loss or anemia.

Mechanism

[edit]Reticulocytosis results from the body’s physiological response to an increased need for red blood cells. When red blood cells are destroyed or lost, tissues experience low oxygen levels causing the kidneys to release the hormone erythropoietin. Erythropoietin signals the bone marrow to accelerate the production of red blood cells through a process called erythropoiesis. As a result, more reticulocytes are released into the bloodstream. These immature cells continue to mature into fully developed red blood cells in circulation, restoring the red cell count and supporting oxygen delivery to tissues.[3]

Causes

[edit]Hemolytic Anemia

[edit]Broad category of anemias where red blood cells are destroyed faster than they can be replaced, prompting the bone marrow to increase red blood cell production and the release of immature red blood cells into the bloodstream.[4] Reticulocytosis provides strong suspicion of hemolysis when present along with many other markers like elevations in lactate dehydrogenase and unconjugated bilirubin or a decrease in haptoglobin.[4]

- Sickle cell anemia: a genetic disorder where abnormal hemoglobin (HbS) causes red blood cells to become rigid and sickle-shaped, leading to intermittent blood vessel blockages, hemolysis, and tissue ischemia. Destruction of these defective red blood cells results in anemia, which stimulates the bone marrow to increase red blood cell production. Because of this, reticulocytosis is a possible lab finding in sickle cell disease.[5]

- Hereditary spherocytosis: a genetic disorder where defects in red blood cell membrane proteins cause them to lose their normal shape, becoming spherical (spherocytes) which are prone to getting stuck and rupturing in the spleen. This hemolysis creates a chronic shortage of red blood cells, stimulating the bone marrow to increase production and release reticulocytes into circulation.[6]

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency: a genetic disorder that makes red blood cells vulnerable to oxidative stress. When individuals with this deficiency consume fava beans, experience stress or are exposed to certain medications, oxidative damage leads to red blood cell destruction (hemolysis). In response to this rapid hemolysis, the bone marrow increases RBC production, resulting in reticulocytosis as it attempts to replace the destroyed cells.[7]

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia: caused by the host immune system attacking and destroying its own red blood cells. In response to this, the bone marrow will begin to produce more red blood cells to compensate for this destruction.[8]

Blood Loss

[edit]In response to significant blood loss, either acute (e.g., trauma or surgery) or chronic (e.g., gastrointestinal bleeding), the bone marrow increases production to replace lost red blood cells. This results in an increased reticulocyte count, as new immature cells are released and make up a larger proportion of the blood volume.[2]

Pregnancy

[edit]During pregnancy, folate deficiency can cause megaloblastic anemia in the mother and poses a significant neurological developmental risk for the fetus. Upon initiation of maternal folate supplementation to prevent fetal abnormalities, reticulocytosis is expected after 3–4 days of treatment.[9]

Diagnosis

[edit]Reticulocytosis is typically diagnosed through a reticulocyte count, which measures the percentage or absolute number of reticulocytes in the blood. Common diagnostic tools for hematological disorders that may cause reticulocytosis include:

Reticulocyte Production Index (RPI): Calculation that corrects for reticulocytes counts that may be misleadingly elevated due to the decrease in total red blood cells seen in anemia. Calculated as [%reticulocyte count x Patient Hct] / 45(normal Hct). This adjustment provides insight into whether reticulocyte production is adequate for the level of anemia.[1]

Complete Blood Count (CBC): Provides a value for a variety of blood components, including red blood cells, hemoglobin, and hematocrit levels. [10]

Peripheral Blood Smear: Common lab test in the work up of blood disorders that evaluates the size, shape, and maturity of red blood cells and reticulocytes by observing them under a microscope.[11]This can help narrow down the etiology of the reticulocytosis.

Treatment

[edit]The management of reticulocytosis involves treating the underlying cause rather than attempting to treat the high reticulocyte count itself.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Gaur, Malvika; Sehgal, Tushar (2021-09-02). "Reticulocyte count: a simple test but tricky interpretation!". The Pan African Medical Journal. 40: 3. doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.40.3.31316. PMC 8490160. PMID 34650653.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ a b Rai, Dipti; Wilson, Allecia M.; Moosavi, Leila (2024), "Histology, Reticulocytes", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31194329, retrieved 2024-11-11

- ^ Bhoopalan, Senthil Velan; Huang, Lily Jun-shen; Weiss, Mitchell J. (2020-09-18). "Erythropoietin regulation of red blood cell production: from bench to bedside and back". F1000Research. 9: F1000 Faculty Rev. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26648.1. PMC 7503180. PMID 32983414.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Baldwin, Caitlin; Pandey, Jyotsna; Olarewaju, Olubunmi (2024), "Hemolytic Anemia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32644330, retrieved 2024-11-11

- ^ Mangla, Ankit; Ehsan, Moavia; Agarwal, Nikki; Maruvada, Smita (2024), "Sickle Cell Anemia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29489205, retrieved 2024-11-12

- ^ Wu, Yangyang; Liao, Lin; Lin, Faquan (2021-10-24). "The diagnostic protocol for hereditary spherocytosis‐2021 update". Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 35 (12): e24034. doi:10.1002/jcla.24034. PMC 8649336. PMID 34689357.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Beretta, Alice; Manuelli, Matteo; Cena, Hellas (2023-01-10). "Favism: Clinical Features at Different Ages". Nutrients. 15 (2): 343. doi:10.3390/nu15020343. PMC 9864644. PMID 36678214.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hill, Anita; Hill, Quentin A. (2018-11-30). "Autoimmune hemolytic anemia". Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2018 (1): 382–389. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.382. ISSN 1520-4383. PMC 6246027. PMID 30504336.

- ^ Arnett, Christina; Greenspoon, Jeffrey S.; Roman, Ashley S. (2019), DeCherney, Alan H.; Nathan, Lauren; Laufer, Neri; Roman, Ashley S. (eds.), "Hematologic Disorders in Pregnancy", CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Obstetrics & Gynecology (12 ed.), New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education, retrieved 2024-11-12

- ^ El Brihi, Jason; Pathak, Surabhi (2024), "Normal and Abnormal Complete Blood Count With Differential", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 38861622, retrieved 2024-11-11

- ^ Lynch, Edward C. (1990), Walker, H. Kenneth; Hall, W. Dallas; Hurst, J. Willis (eds.), "Peripheral Blood Smear", Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations (3rd ed.), Boston: Butterworths, ISBN 978-0-409-90077-4, PMID 21250106, retrieved 2024-11-11