Rök runestone

58°17′42″N 14°46′32″E / 58.29500°N 14.77556°E

| Rök runestone | |

|---|---|

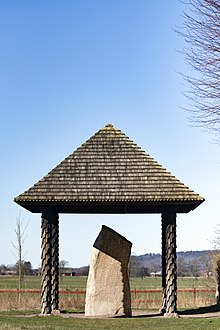

The stone under its protection roof in 2020. | |

| Height | 2.4 m (8 feet) |

| Weight | 5.1 tons |

| Writing | Younger Futhark |

| Created | 800 CE |

| Discovered | 19th century Rök, Östergötland, Sweden |

| Present location | Rök, Ödeshög Municipality, Östergötland, Sweden |

| Culture | Norse |

| Rundata ID | Ög 136 |

| Style | RAK |

| Runemaster | Varinn |

| Text – Native | |

| Old Norse: See article. | |

| Translation | |

| See article. | |

The Rök runestone (Swedish: Rökstenen; Ög 136) is one of the most famous runestones, featuring the longest known runic inscription in stone. It can now be seen beside the church in Rök, Ödeshög Municipality, Östergötland, Sweden. It is considered the first piece of written Swedish literature and thus it marks the beginning of the history of Swedish literature.[1][2]

About the stone

[edit]

The 5 long tons (5.1 t), 8 feet (2.4 m) tall stone[3] was discovered built into the wall of a church in the 19th century and removed from the church wall a few decades later. The church was built in the 12th century, and it was common to use rune stones as building material for churches. The stone was probably carved in the early 9th century,[3] judging from the main runic alphabet used ("short-twig" runes) and the form of the language. It is covered with runes on five sides except the base which was to be put under ground. A few parts of the inscription are damaged, but most of it remains legible.

The name "Rök Stone" is something of a tautology: the stone is named after the village, "Rök", but the village is probably named after the stone, "Rauk" or "Rök" meaning "skittle-shaped stack/stone" in Old Norse.

The stone is unique in a number of ways. It contains a fragment of what is believed to be a lost piece of Norse mythology. It also makes a historical reference to Ostrogothic king (effectively emperor of the western Roman empire) Theodoric the Great. It contains the longest extant pre-Christian runic inscription – around 760 characters[3] – and it is a virtuoso display of the carver's mastery of runic expression.

The inscription is partially encrypted in two ways; by displacement and by using special cipher runes. The inscription is intentionally challenging to read, using kennings in the manner of Old Norse skaldic poetry, and demonstrating the carver's command of different alphabets and writing styles (including code). The obscurity may perhaps even be part of a magic ritual.

Inscription

[edit]

Unicode

[edit]This is a direct Unicode transliteration of the runes, as close to the scriptio continua original as possible. Ciphers are within brackets, with the resolution following the equals sign:

ᛆᚠᛏᚢᛆᛘᚢᚦᛌᛏᚭᚿᛏᛆᚱᚢᚿᛆᛧᚦᛆᛧ ᛭ ¶ ᚿᚢᛆᚱᛁᚿᚠᛆᚦᛁᚠᛆᚦᛁᛧᛆᚠᛐᚠᛆᛁᚴᛁᚭᚿᛌᚢᚿᚢ ¶ ᛌᛆᚴᚢᛘᚢᚴᛘᛁᚿᛁᚦᛆᛐᚽᚢᛆᚱᛁᛆᛧᚢᛆᛚᚱᛆᚢᛓᛆᛧᚢᛆᛧᛁᚿᛐᚢᛆᛧ ¶ ᚦᛆᛧᛌᚢᛆᚦᛐᚢᛆᛚᚠᛌᛁᚿᚢᛘᚢᛆᛧᛁᚿᚢᛘᚿᛆᛧᛐᚢᛆᛚᚱᛆᚢᛓᚢ ¶ ᛓᛆᚦᛆᛧᛌᚭᛘᚭᚿᚭᚢᛘᛁᛌᚢᛘᚭᚿᚢᛘ ᛫ ᚦᛆᛐᛌᛆᚴᚢᛘᚭᚿᛆ ¶ ᚱᛐᚽᚢᛆᛧᚠᚢᚱᚿᛁᚢᛆᛚᛐᚢᛘᚭᚿᚢᚱᚦᛁᚠᛁᛆᚱᚢ ¶ ᛘᛁᛧᚽᚱᛆᛁᚦᚴᚢᛐᚢᛘᛆᚢᚴᛐᚢ ¶ ᛘᛁᛧᚭᚿᚢᛓᛌᛆᚴᛆᛧ ¶

ᚱᛆᛁᚦᛁᛆᚢᚱᛁᚴᛧᚽᛁᚿᚦᚢᚱᛘᚢᚦᛁᛌᛐᛁᛚᛁᛧ ¶ ᚠᛚᚢᛐᚿᛆᛌᛐᚱᚭᚿᛐᚢᚽᚱᛆᛁᚦᛘᛆᚱᛆᛧᛌᛁᛐᛁᛧᚿᚢᚴᛆᚱᚢᛧᚭ ¶ ᚴᚢᛐᛆᛌᛁᚿᚢᛘᛌᚴᛁᛆᛚᛐᛁᚢᛓᚠᛆᛐᛚᛆᚦᛧᛌᚴᛆᛐᛁᛘᛆᚱᛁᚴᛆ ¶

ᚦᛆᛐᛌᛆᚴᚢᛘᛐᚢᛆᛚᚠᛐᛆᚽᚢᛆᚱᚽᛁᛌᛐᛧᛌᛁᚴᚢ ¶ ᚿᛆᛧᛁᛐᚢᛁᛐᚢᚭᚴᛁᚭᚿᚴᚢᚿᚢᚴᛆᛧᛐᚢᛆᛁᛧᛐᛁᚴᛁᛧᛌᚢᛆ ¶ ᚦᚭᛚᛁᚴᛁᛆ ᛭ ᚦᛆᛐᛌᛆᚴᚢᛘᚦᚱᛁᛐᛆᚢᚿᛐᛆᚽᚢᛆᚱᛁᛧᛐ ¶ ᚢᛆᛁᛧᛐᛁᚴᛁᛧᚴᚢᚿᚢᚴᛆᛧᛌᛆᛐᛁᚿᛐᛌᛁᚢᛚᚢᚿᛐᛁᚠᛁᛆ ¶ ᚴᚢᚱᛆᚢᛁᚿᛐᚢᚱᛆᛐᚠᛁᛆᚴᚢᚱᚢᛘᚿᛆᛓᚿᚢᛘᛓᚢᚱᚿ ¶ ᛧᚠᛁᛆᚴᚢᚱᚢᛘᛓᚱᚢᚦᚱᚢᛘ ᛭ ᚢᛆᛚᚴᛆᛧᚠᛁᛘᚱᛆ=ᚦᚢᛚᚠᛌᚢ ¶ ᚿᛁᛧᚽᚱᛆᛁᚦᚢᛚᚠᛆᛧᚠᛁᛘᚱᚢᚴᚢᛚᚠᛌᚢᚿᛁᛧᚽᚭᛁᛌᛚᛆᛧᚠᛁᛘᚽᛆᚱᚢᚦ ¶ ᛌᛌᚢᚿᛁᛧᚴᚢᚿᛘᚢᚿᛐᛆᛧᚠᛁᛘ(ᛓ)ᛁᚱᚿᛆᛧᛌᚢᚿᛁᛧ ¶ ᚿᚢᚴᛘ---(ᛘ)-- ᛆᛚᚢ --(ᚴ)(ᛁ)ᛆᛁᚿᚽᚢᛆᛧ-ᚦ... ...ᚦ... × ᚠᛐᛁᛧᚠᚱᛆ ¶

ᛋᛃᚷᚹᛗᛟᚷᛗᛖᚿᛇ[3:3 = ᚦ]ᛃᛞᚺᛟᛃᛦᛇᚷᛟᛚᛞ ¶ ᚷᛃᛟᛃᛦᛇᚷᛟᛚᛞᛁᚿᛞᚷᛟᚭᚿᛃᛦᚺᛟᛋᛚᛇ ¶

[ᛆᛁᚱᚠᛓᚠᚱᛓᚿᚽᚿᚠᛁᚿᛓᛆᚿᛐᚠᚭᚿᚽᚿᚢ = ᛌᛆᚴᚢᛙᚢᚴᛙᛁᚿᛁᚢᛆᛁᛙᛌᛁᛓᚢᚱᛁᚿᛁᚦ] ¶ ᛧᛐᚱᚭᚴᛁᚢᛁᛚᛁᚿᛁᛌᚦᛆᛐ ᛭ [ᚱᚽᚠᚦᚱᚽᛁᛌ = ᚴᚿᚢᚭᚴᚾᛆᛐ] ¶ ᛁᛆᛐᚢᚿᚢᛁᛚᛁᚿᛁᛌᚦᛆᛐ ᛭ [2:2 = ᚿ] [2:3 = ᛁ] [1:1 = ᛐ] ¶

[3:2 = ᚢ] [1:4 = ᛚ] ¶ [2:2 = ᚿ] [2:3 = ᛁ] ¶ [3:5 = ᚱ] [3:2 = ᚢ]ᚦᛧ ¶ [2:5 = ᛌ] [2:3 = ᛁ]ᛓᛁ ¶ [3:2 = ᚢ] [2:3 = ᛁ]ᛆ ¶ [3:2 = ᚢ] [2:4 = ᛆ]ᚱᛁ ¶

([2:5 = ᛌ]) [2:4 = ᛆ] [3:6 = ᚴ] [3:2 = ᚢ] [1:3 = ᛙ] [3:2 = ᚢ] [3:6 = ᚴ] [1:3 = ᛙ] [2:3 = ᛁ] [2:2 = ᚿ] [2:3 = ᛁ] ¶ [3:3 = ᚦ] [3:2 = ᚢ] [3:5 = ᚱ]

Latin transliteration

[edit]This is a transliteration of the runes, with ciphers resolved and spaces added between word boundaries:

aft uamuþ stąnta runaʀ þaʀ ᛭ ¶ n uarin faþi faþiʀ aft faikiąn sunu ¶ sakum| |mukmini þat huariaʀ ualraubaʀ uaʀin tuaʀ ¶ þaʀ suaþ tualf sinum uaʀin| |numnaʀ t ualraubu ¶ baþaʀ sąmąn ą umisum| |mąnum · þat sakum ąna¶rt huaʀ fur niu altum ąn urþi fiaru ¶ miʀ hraiþkutum auk tu ¶ miʀ ąn ub sakaʀ ¶

raiþ| |þiaurikʀ hin þurmuþi stiliʀ ¶ flutna strąntu hraiþmaraʀ sitiʀ nu karuʀ ą ¶ kuta sinum skialti ub fatlaþʀ skati marika ¶

þat sakum tualfta huar histʀ si ku¶naʀ itu| |uituąki ąn kunukaʀ tuaiʀ tikiʀ sua¶þ ą likia ᛭ þat sakum þritaunta huariʀ t¶uaiʀ tikiʀ kunukaʀ satin t siulunti fia¶kura uintur at fiakurum nabnum burn¶ʀ fiakurum bruþrum ᛭ ualkaʀ fim ra=þulfs| |su¶niʀ hraiþulfaʀ fim rukulfs| |suniʀ hąislaʀ fim haruþ¶s suniʀ kunmuntaʀ fim (b)irnaʀ suniʀ ¶ ᛭ nuk m--- [m]-- alu --[k][i] ainhuaʀ -þ... ...þ ... ftiʀ fra ¶

sᴀgwm| |mogmenï (þ)ᴀd hoᴀʀ igold¶gᴀ oᴀʀï goldin d goąnᴀʀ hoslï ¶

sakum| |mukmini uaim si burin| |niþ¶ʀ trąki uilin is þat ᛭ knuą knat¶i| |iatun uilin is þat ᛭ (n)(i)(t) ¶

ul ¶ ni¶ruþʀ ¶ sibi ¶ uia¶uari ¶

[s]akum| |mukmini ¶ þur

Old East Norse transcription

[edit]This is a transcription of the runes in early 9th century Old East Norse (Swedish and Danish) dialect of Old Norse. The first part is written in ljóðaháttr meter, and the part about Theoderic is written in the fornyrðislag meter:

Æft Wǣmōð/Wāmōð stąnda rūnaʀ þāʀ. Æn Warinn fāði, faðiʀ, æft fæigjąn sunu. Sagum mōgminni/ungmænni þat, hwærjaʀ walrauƀaʀ wāʀin twāʀ þāʀ, swāð twalf sinnum wāʀin numnaʀ at walrauƀu, bāðaʀ sąmąn ą̄ ȳmissum mąnnum. Þat sagum ąnnart, hwaʀ for nīu aldum ą̄n urði fiaru meðr Hræiðgutum, auk dō meðr/dœmiʀ hann/enn umb sakaʀ. Rēð Þiaurikʀ hinn þurmōði, stilliʀ flutna, strąndu Hræiðmaraʀ. Sitiʀ nū garwʀ ą̄ guta sīnum, skialdi umb fatlaðʀ, skati Mǣringa. Þat sagum twalfta, hwar hæstʀ sē Gunnaʀ etu wēttwąngi ą̄, kunungaʀ twæiʀ tigiʀ swāð ą̄ liggia. Þat sagum þrēttaunda, hwariʀ twæiʀ tigiʀ kunungaʀ sātin at Siolundi fiagura wintur at fiagurum naƀnum, burniʀ fiagurum brø̄ðrum. Walkaʀ fimm, Rāðulfs syniʀ, Hræiðulfaʀ fimm, Rugulfs syniʀ, Hāislaʀ fimm, Hāruðs syniʀ, Gunnmundaʀ/Kynmundaʀ fimm, Biarnaʀ syniʀ. Nū 'k m[inni] m[eðr] allu [sa]gi. Æinhwaʀʀ ... [swā]ð ... æftiʀ frā. Sagum mōgminni/ungmænni þat, hwaʀ Inguldinga wāʀi guldinn at kwą̄naʀ hūsli. Sagum mōgminni/ungmænni, hwæim sē burinn niðʀ dræ̨ngi. Wilinn es þat. Knūą/knyią knātti iatun. Wilinn es þat ... Sagum mōgminni/ungmænni: Þōrr. Sibbi wīawæri ōl nīrø̄ðʀ.

Old West Norse transcription

[edit]This is a transcription of the runes in the classic 13th century Old West Norse (Norwegian and Icelandic) dialect of Old Norse:

Ept Vémóð/Vámóð standa rúnar þær. En Varinn fáði, faðir, ept feigjan son. Sǫgum múgminni/ungmenni þat, hverjar valraufar væri tvær þær, svát tolf sinnum væri numnar at valraufu, báðar saman á ýmissum mǫnnum. Þat sǫgum annat, hverr fyrir níu ǫldum án yrði fjǫr með Hreiðgotum, auk dó meðr/dœmir hann/enn of sakar. Réð Þjórekr, hinn þormóði stillir flotna, strǫndu Hreiðmarar. Sitr nú gǫrr á gota sínum, skildi of fatlaðr, skati Mæringa. Þat sǫgum tolfta, hvar hestr sé Gunnar etu véttvangi á, konungar tveir tigir svát á liggja. Þat sǫgum þrettánda, hverir tveir tigir konungar sæti at Sjólundi fjóra vetr at fjórum nǫfnum, bornir fjórum brœðrum. Valkar fimm, Ráðulfs synir, Hreiðulfar fimm, Rugulfs synir, Háislar fimm, Hǫrðs synir, Gunnmundar/Kynmundar fimm, Bjarnar synir. Nú'k m[inni] m[eð] ǫllu [se]gi. Einhverr ... [svá]t ... eptir frá. Sǫgum múgminni/ungmenni þat, hvar Ingoldinga væri goldinn at kvánar húsli. Sǫgum múgminni/ungmenni, hveim sé borinn niðr drengi. Vilinn er þat. Knúa/knýja knátti jǫtun. Vilinn er þat ... Sǫgum múgminni/ungmenni: Þórr. Sibbi véaveri ól nírœðr.

Translation

[edit]

The following is the "standard" translation of the text provided by Rundata;[4] most researchers agree on how the runes have been deciphered, but the interpretation of the text and the meaning are still a subject of debate.

In memory of Vámóðr stand these runes. And Varinn coloured them, the father, in memory of his dead son.

I say the folktale / to the young men, which the two war-booties were, which twelve times were taken as war-booty, both together from various men.

I say this second, who nine generations ago lost his life with the Hreidgoths; and died with them for his guilt.

Þjóðríkr the bold,

chief of sea-warriors,

ruled over the shores

of the Hreiðsea.

Now he sits armed on

§B his Goth(ic horse),

his shield strapped,

the prince of the Mærings.

§C I say this the twelfth, where the horse of Gunnr sees fodder on the battlefield, where twenty kings lie.

This I say as thirteenth, which twenty kings sat on Sjólund for four winters, of four names, born of four brothers:

five Valkis, sons of Ráðulfr,

five Hreiðulfrs, sons of Rugulfr,

five Háisl, sons of Hǫrðr,

five Gunnmundrs/Kynmundrs, sons of Bjǫrn.

Now I say the tales in full. Someone …

I say the folktale / to the young men, which of the line of Ingold was repaid by a wife's sacrifice.

I say the folktale / to the young men, to whom is born a relative, to a valiant man. It is Vélinn. He could crush a giant. It is Vélinn …

§D I say the folktale / to the young men: Þórr.

§E Sibbi of Vé, §C nonagenarian, begot (a son).

Theodoric Strophe

[edit]

Interpretation

[edit]This article possibly contains original research. (August 2022) |

Apart from Theodoric, Gunnr and the Norse god Thor, the people and mythological creatures mentioned are unknown. Some interpretations have been suggested:

The two war-booties are likely to be two precious weapons, such as a sword and a shield or a helmet. Several stories like these exist in old Germanic poems.

The Hreidgoths mentioned are a poetic name for the Ostrogoths, appearing in other sources. To what sea the name Hreiðsea Eastern Sea, referred is unknown. The part about Theodoric (who died in 526 A.D.) probably concerns the statue of him sitting on his horse in Ravenna, which was moved in 801 A.D. to Aachen by Charlemagne.[5] This statue was very famous and portrayed Theodoric with his shield hanging across his left shoulder, and his lance extended in his right hand. The Mærings is a name for Theodoric's family.[citation needed] According to the old English Deor poem from the 10th century, Theodoric ruled the "castle of the Mærings" (Ravenna) for thirty years. The words about Theodoric may be connected to the previous statement, so the stone is talking about the death of Theodoric: he died approximately nine generations before the stone was carved, and the church considered him a cruel and godless emperor, thus some may have said that he died for his guilt.

Gunnr whose "horse sees fodder on the battlefield" is presumably a Valkyrie (previously known from Norse mythology), and her "horse" is a wolf. This kind of poetic license is known as kenning in the old Norse poetry tradition.

The story about the twenty kings says that the twenty were four groups of five brothers each, and in each of these four groups, all brothers shared the same names, and their fathers were four brothers (4 × 5 = 20). This piece of mythology seems to have been common knowledge at the time, but has been totally lost. The Sjólund is similar to the name given to Roslagen by Snorri Sturluson but it has often been interpreted as Sjælland where the Iron Age Lejre Kingdom lay, (nowadays a part of Denmark).

Starting with the Ingold-part, the text becomes increasingly hard to read. While the first part is written in the 16 common short-twig runes in the Younger Futhark, Varinn here switches over to using the older 24-type Elder Futhark and cipher runes. It has been assumed that this is intentional, and that the rows following this point concern legends connected specifically to Varinn and his tribe.

After the word It is Vélinn ... follows the word Nit. This word remains uninterpreted, and its meaning is unclear.

In the last line, the carver invokes the god Thor and then he says that Sibbi "of the shrine" begot a son at the age of ninety. Since Thor is evoked before telling about Sibbi's connection with the sanctuary and his potency at old age, it may be a recommendation that being a devout worshipper is beneficial.

Although much in the inscription is difficult to understand, its structure is very symmetrical and easy to perceive: it consists of three parts of (roughly) equal length, each containing two questions and one more or less poetic answer to those questions. As Lars Lönnroth and, after him, Joseph Harris have argued, the form is very similar to the so-called "greppaminni", a sort of poetic riddle game presented by Snorri Sturluson in his Prose Edda.

Theories

[edit]There have been numerous theories proposed about the purpose of the stone. The most common include:

- Varinn carved the stone only to honour his lost son[3] and the inclusion of mythical passages was a tribute from fantasy (Elias Wessén's theory). There is strong evidence to support this view, not the least being the fact that Thor is referenced; this use of a deity in this context is quite conceivably a prefiguration of what was to later become a common practice (anterior to Christianity), where graves were frequently inscribed with runic dedications such as þórr vigi, "may Thor protect you".

- Varinn carved the stone to raise his tribe to vengeance over the death of his son. The dramatic battle mentioned may have been the cause of his son's death. (Otto von Friesen's theory)

- Varinn carved the stone to preserve the tribal myths, as he had the function of a thul, the ceremonial story-teller of his ætt (clan), and this retelling task was to be passed on to his son. Perhaps he feared that the stories could be lost because of the death of his son, and therefore he tried to preserve them in a short form in the stone.[6]

- The stone was a sign to strengthen the position of the tribe leader (since the stone could not be missed by anybody passing the land). He tries to justify his position by showing a long line of powerful ancestors which he follows.

- The battlefield where twenty kings lie has been connected (at least by Herman Lindkvist) to the Battle of Brávellir, which in Norse mythology took place not far from the location of the Rök stone about 50 years earlier.

- According to a hypothesis put forward by Åke Ohlmarks, Varinn was the local chieftain and as such also the one who performed sacrifices to the gods. Then arrived Ansgar, the first to bring Christianity to Sweden, and the wife of Varinn's son Vémóðr/Vámóðr was baptized by him. Therefore, Varinn was forced to sacrifice his own son to the gods as indicated in the verse: "I say the folktale / to the young men, which of the line of Ingold was repaid by a wife's sacrifice" (the word "husl" can be interpreted both "sacrifice" and "baptism"). Shortly: Vémóðr/Vámóðr paid with his life for his wife's betrayal to the gods and Varinn had to kill his own son. That might also be the reason that Varinn used the word "faigian" (who is soon to die) instead of "dauðan" (dead) in the first line.[7]

- Researchers at three Swedish universities (University of Gothenburg, Uppsala University and Stockholm University) hypothesize that the inscription alludes to climate crisis, Fimbulwinter, following the extreme weather events of 535–536, which occurred 300 years earlier, taking into consideration: the strongest known solar storm (774–775 carbon-14 spike) with its documented red skies, the exceptionally cold summer of 775 CE which affected crop yields, and the almost total solar eclipse in 810 CE, which gave the impression that the sun was extinguished shortly after dawn.[8]

- In 2015, it was proposed that the inscription has nothing at all to do with the recording of heroic sagas and that it contains riddles which refer only to the making of the stone itself.[9][10]

In popular culture

[edit]- A transcription of the runes feature on the cover of the 1990 Black Sabbath album Tyr.[11]

- Swedish Viking metal band King of Asgard released in 2010 the song "Vämods Tale". The translation of the Rök runestone forms the song's lyrics.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gustafson, Alrik, Svenska litteraturens historia, 2 volums (Stockholm, 1963). First published as A History of Swedish Literature (American-Scandinavian Foundation, 1961). Chapter 1.

- ^ Forntid och medeltid, Lönnroth, in Lönnroth, Göransson, Delblanc, Den svenska litteraturen, vol 1.

- ^ a b c d Weiss, Daniel (July–August 2020). "The Emperor of Stones". Archaeology. 73 (4): 9–10. ISSN 0003-8113.

- ^ "Runic inscription Ög 136", Scandinavian Runic-text Database, Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala University, 2020, retrieved December 19, 2021

- ^ Andren, A. Jennbert, K. Raudvere, C. "Old Norse Religion: Some Problems and Prospects" in Old Norse Religion in Long Term Perspectives: Origins, Changes and Interactions, an International Conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3-7, 2004. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 91-89116-81-X p. 11.

- ^ Widmark, Gun. "Rökstenens hemlighet" (in Swedish). Forskning och Framsteg. Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ^ Ohlmarks, Åke (1979). Vårt nordiska arv. Från 10.000 f.Kr. till medeltidens början. Stockholm: Stureförlaget. pp. 228–229. ASIN B0000ED2SR. OCLC 186682264.

- ^ Holmberg, Per; Gräslund, Bo; Sundqvist, Olof; Williams, Henrik (2020). "The Rök Runestone and the End of the World" (PDF). Futhark: International Journal of Runic Studies. 9–10: 7–38. doi:10.33063/diva-401040.

- ^ Holmberg, Per (2015). "Svaren på Rökstenens gåtor : En socialsemiotisk analys av meningsskapande och rumslighet" [Answers to the Rök runestone riddles: A social semiotic study of meaning-making and spatiality]. Futhark: International Journal of Runic Studies. 6: 65–106.

- ^ "New Interpretation of the Rök Runestone Inscription Changes View of Viking Age". University of Gothenburg. 2016-05-02. Retrieved 2024-08-18.

- ^ "Tyr – Black Sabbath Online".

Sources

[edit]- Bugge, Sophus: Der Runenstein von Rök in Östergötland, Schweden, Stockholm 1910

- von Friesen, Otto: Rökstenen, Uppsala 1920

- Grönvik, Ottar: "Runeinnskriften på Rökstenen" in Maal og Minde 1983, Oslo 1983

- Gustavson, Helmer: Rökstenen (produced by Swedish National Heritage Board), Uddevalla 2000, ISBN 91-7192-822-7

- Harris, Joseph. "The Rök Inscription, Line 20." In New Norse Studies: Essays on the Literature and Culture of Medieval Scandinavia, edited by Jeffrey Turco, 321–344. Islandica 58. Ithaca: Cornell University Library, 2015. http://cip.cornell.edu/cul.isl/1458045719

- Harris, Joseph: "Myth and Meaning in the Rök Inscription", Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, 2 (2006), 45-109, DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1484/J.VMS.2.302020.

- Jansson, Sven B F: Runinskrifter i Sverige, Stockholm 1963, 3rd edition in 1984

- Lönnroth, Lars: "The Riddles of the Rök-Stone: A Structural Approach", Arkiv för nordisk filologi 92 (1977), reprinted in The Academy of Odin: Selected Papers on Old Norse Literature, Odense 2011

- Rydberg, Viktor: Om Hjältesagan å Rökstenen, Stockholm, 1892; translated as "The Heroic Saga on the Rökstone" by William P. Reaves, The Runestone Journal 1, Asatru Folk Assembly, 2007. OCLC 2987129.

- Schück, Henrik: "Bidrag till tolkningen af Rökstenen" in Uppsala Universitets årsskrift, Uppsala 1908

- Ståhle, Carl Ivar and Tigerstedt, E N: Sveriges litteratur. Del 1. Medeltidens och reformationstidens litteratur, Stockholm, 1968.

- Wessén, Elias: Runstenen vid Röks kyrka, Stockholm, 1958.