Wakarusa River

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

| Wakarusa River | |

|---|---|

Falls of the Wakarusa River | |

| |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kansas |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Wabaunsee County, Kansas |

| • coordinates | 38°53′44″N 95°57′36″W / 38.89556°N 95.96000°W |

| • elevation | 1,261 ft (384 m) |

| Mouth | Kansas River |

• location | Eudora, Kansas |

• coordinates | 38°57′22″N 95°04′56″W / 38.95611°N 95.08222°W[2] |

• elevation | 781 ft (238 m) |

| Length | 80.5 mi (129.6 km) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | USGS 06891500 near Lawrence, KS[1] |

| • average | 219 cu ft/s (6.2 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 0 cu ft/s (0 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 22,600 cu ft/s (640 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Wakarusa—Kansas—Missouri—Mississippi |

The Wakarusa River is a tributary of the Kansas River, approximately 80.5 miles (129.6 km) long,[3] in eastern Kansas in the United States. It drains an agricultural area of rolling limestone hills south of Topeka and Lawrence.

Description

[edit]It rises in several branches located southwest of Topeka. The main branch rises on the Wabaunsee-Shawnee county line, approximately 10 miles (16 km) southwest of Topeka and flows east. The South Branch rises in eastern Wabaunsee County, approximately 15 miles (24 km) southwest of Topeka and flows east-northeast, joining the main branch south of Topeka.

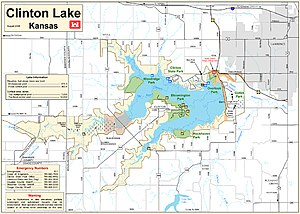

The main branch flows generally east, flowing south of Lawrence. It joins the Kansas River in Douglas County at Eudora, approximately 8 miles (13 km) east of Lawrence. It is impounded by Clinton Dam approximately 3 miles (5 km) southwest of Lawrence to form Clinton Lake.

The river is known for its gentle current that winds through river-level outcropping rocks, primarily of Pennsylvanian limestone. This reach of the river was inhabited by different Native American tribes, including the Kansa and Osage Nation in the 18th century.

During 1819-1820, Major Stephen H. Long referred to this tributary as "Warreruza".[4] According to a 1912 encyclopedia, the name comes from an Indian legend, wherein a young woman was crossing the river on horseback. She exclaimed "Wakarusa!", meaning "hip deep", and the name stuck.[5] The meanings "thigh deep" and "river of thick weeds" are also recorded.[6]

After the U.S. acquired this region, the Shawnee people were relocated here during the early 19th century. Ridgelines of this historic watershed defined wagon train routes first used by Santa Fe Trail pioneers and Oregon Trail emigrants.

During the Great Migration of 1843, the fords used for crossing this meandering river were among the many topographic challenges emigrant wagon trains had to master along the Fremont-Westport Trail (1843-1848) named after John C. Frémont. This Freedom's Frontier route also was called the California Road during the 1849 gold rush.

Also, during the days of the Kansas Territory, the limestone outcroppings of the river presented great challenges to early white emigrants attempting to ford the stream in their wagons. Oregon Trail wagons were often dismantled, lowered down the limestone beds, towed across, then lifted by rope to the opposing bank.

Several Shawnee created ferry operations at river crossings in the 1850s, including Blue Jacket's Ferry near Coal Creek at Sebastian. The river's gentle current and scenic banks made it an early recreation spot for citizens of Lawrence (which was originally called "Wacharusa"). See Indian Territory (1820-1840)

The river once had extensive wetland riparian habitat, much of which has been reclaimed over the last century for cultivation and other uses. Clinton Dam, finished in 1977 to reduce seasonal spring flooding, greatly reduced the replenishment of wetlands below the dam. A remaining tract of 600 acres (2.4 km2), the Haskell-Baker Wetlands, is located south of Lawrence near Haskell Indian Nations University.

Though the wetlands below the dam are mostly dry now, along the Wakarusa above Clinton Lake, former cropland has been converted into a new wetland area. By pumping water into shallow ditches, 3 major manmade wetlands have formed, including the East and West Coblentz marshes, and the more recent Elk Creek wetland add more than 500 acres (2.0 km2) of wetlands along the Wakarusa River. The East and West Coblentz complexes are more accessible than the Elk Creek complex, and boast a large variety of waterfowl and reptiles. Due to the wetlands lying within the low Clinton Lake floodpool, access is very limited during the wet spring months.

Tributaries and other landmarks

[edit](This list follows Wakarusa River flow downstream)

- Middle Branch Wakarusa

- South Branch Wakarusa

- North Branch Wakarusa

- Six Mile Creek

- Towhead Creek

- Bury's Creek

- Lynn Creek

- Camp Creek

- Elk-Horn Creek

- Dry Creek

- Deer Creek

- Coon Creek

- Clinton Lake - Elev: 876 ft (267 m)

- South Rock Creek

- Washington Creek

- Yankee Tank Creek

- USGS Gaging Station - Elev: 799 ft (244 m)

- Black Jack Creek (COAL CREEK), trib. of Wakarusa River; Douglas Co. USGS: Lawrence E.

- Spring Creek

- Little Wakarusa Creek

Cities along the Wakarusa River

[edit]- Auburn, Kansas - Elev: 1,083 ft (330 m)

- Wakarusa, Kansas (unincorporated) - Elev: 955 ft (291 m)

- Richland, Kansas (unincorporated) - Elev: 925 ft (282 m)

- Eudora - Elev: 785 ft (239 m)

See also

[edit]- Bleeding Kansas Heritage Area

- California Road - Branch of the Oregon Trail to Lawrence, Kansas from Westport Landing.

- Clinton State Park - Provides recreational access to Clinton Lake.

- Wakarusa War

- List of Kansas rivers

References

[edit]- ^ "Water-Data Report 2012 - 06891500 Wakarusa River near Lawrence, KS" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ^ "Wakarusa River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map, accessed March 30, 2011

- ^ Van Meter McCoy, Sondra & Hults, Jan. 1001 Kansas Place Names. University Press of Kansas, 1989, p. 203.

- ^ Blackmar, Frank Wilson (1912). Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume 2. Standard Publishing Company. pp. 854.

- ^ James, Edwin (September 20, 2018). Early Western Travels 1748-1846: Volume XIV. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 9783734010712 – via Google Books.

External links

[edit]Human geography

[edit]- Bluejacket Crossing

- Old West Kansas Historic Trails

- Part I of James's Account of S. H. Long's Expedition, 1819--1820 (p. 184)

Physical geography

[edit]- Fresh water supplies: Out of the tap (series)

- KWO: Kansas-Lower Republican Basin