Minimalism

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Top: Untitled, by Donald Judd, concrete sculpture, 1991, Israel Museum Centre: the Zollverein School of Management and Design Essen, Germany, 2005–2006, by SANAA Bottom: Kazimir Malevich, Black Square, 1915, oil on canvas, 79.5 x 79.5 cm, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow | |

| Years active | 1960s–present |

|---|---|

In visual arts, music and other media, minimalism is an art movement that began in the post-war era in Western art. The movement is often interpreted as a reaction to abstract expressionism and modernism; it anticipated contemporary post-minimal art practices, which extend or reflect on minimalism's original objectives.[1] Minimalism's key objectives were to strip away conventional characterizations of art through bringing the importance of the object or the experience a viewer has for the object with minimal mediation from the artist.[2]Prominent artists associated with minimalism include Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, Robert Morris, Anne Truitt and Frank Stella.[3]

Minimalism in music often features repetition and gradual variation, such as the works of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Julius Eastman and John Adams. The term has also been used to describe the plays and novels of Samuel Beckett, the films of Robert Bresson, the stories of Raymond Carver, and the automobile designs of Colin Chapman.

In recent years, Minimalism has come to refer to anything or anyone that is spare or stripped to its essentials.[4]

Visual arts

[edit]

Minimalism in visual art, sometimes called "minimal art", "literalist art" [5] and "ABC Art",[6] refers to a specific movement of artists that emerged in New York in the early 1960s in response to abstract expressionism.[7] Examples of artists working in painting that are associated with Minimalism include Nassos Daphnis, Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland, Al Held, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Ryman and others; those working in sculpture include Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, David Smith, Anthony Caro and more. Minimalism in painting can be characterized by the use of the hard edge, linear lines, simple forms, and an emphasis on two dimensions.[7] Minimalism in sculpture can be characterized by very simple geometric shapes often made of industrial materials like plastic, metal, aluminum, concrete, and fiberglass;[7] these materials are usually left raw or painted a solid colour.

Minimalism was in part a reaction against the painterly subjectivity of Abstract Expressionism that had been dominant in the New York School during the 1940s and 1950s.[8] Dissatisfied with the intuitive and spontaneous qualities of Action Painting, and Abstract Expressionism more broadly, Minimalism as an art movement asserted that a work of art should not refer to anything other than itself and should omit any extra-visual association.[9]

Donald Judd's work was showcased in 1964 at Green Gallery in Manhattan, as were Flavin's first fluorescent light works, while other leading Manhattan galleries like Leo Castelli Gallery and Pace Gallery also began to showcase artists focused on minimalist ideas.

Minimalism in visual art broadly

[edit]In a more general sense, minimalism as a visual strategy can be found in the geometric abstractions of painters associated with the Bauhaus movement, in the works of Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian and other artists associated with the De Stijl movement, the Russian Constructivist movement, and in the work of the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși.[10][11]

Minimalism as a formal strategy has been deployed in the paintings of Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Josef Albers, and the works of artists as diverse as Pablo Picasso, Yayoi Kusama, Giorgio Morandi, and others. Yves Klein had painted monochromes as early as 1949, and held the first private exhibition of this work in 1950—but his first public showing was the publication of the Artist's book Yves: Peintures in November 1954.[12][13]

Literalism

[edit]

Michael Fried called the minimalist artists literalists, and used literalism as a pejorative due to his position that the art should deliver transcendental experience[14] with metaphors, symbolism, and stylization. Per Fried's (controversial) view, the literalist art needs a spectator to validate it as art: an "object in a situation" only becomes art in the eyes of an observer. For example, for a regular sculpture its physical location is irrelevant, and its status as a work of art remains even when unseen. The Donald Judd's pieces (see the photo on the right), on the other hand, are just objects sitting in the desert sun waiting for a visitor to discover them and accept them as art.[15]

Design, architecture, and spaces

[edit]

This section contains wording that promotes the subject in a subjective manner without imparting real information. (October 2020) |

The term minimalism is also used to describe a trend in design and architecture, wherein the subject is reduced to its necessary elements.[16] Minimalist architectural designers focus on effectively using vacant space, neutral colors and eliminating decoration.[17] Emphasizing materiality, tactility, texture, weight and density.[18] Minimalist architecture became popular in the late 1980s in London and New York,[19] whereby architects and fashion designers worked together in the boutiques to achieve simplicity, using white elements, cold lighting, and large spaces with minimal furniture and few decorative elements.

The works of De Stijl artists are a major reference: De Stijl expanded the ideas of expression by meticulously organizing basic elements such as lines and planes.[20] In 1924, The Rietveld Schroder House was commissioned by Truss Schroder-Schrader, a precursor to minimalism. The house emphasizes its slabs, beams and posts reflecting De Stijls philosophy on the relationship between form and function.[20] With regard to home design, more attractive "minimalistic" designs are not truly minimalistic because they are larger, and use more expensive building materials and finishes.[citation needed]

Minimalistic design has been highly influenced by Japanese traditional design and architecture.[21] There are observers[who?] who describe the emergence of minimalism as a response to the brashness and chaos of urban life. In Japan, for example, minimalist architecture began to gain traction in the 1980s when its cities experienced rapid expansion and booming population. The design was considered an antidote to the "overpowering presence of traffic, advertising, jumbled building scales, and imposing roadways."[22] The chaotic environment was not only driven by urbanization, industrialization, and technology but also the Japanese experience of constantly having to demolish structures on account of the destruction wrought by World War II and the earthquakes, including the calamities it entails such as fire. The minimalist design philosophy did not arrive in Japan by way of another country, as it was already part of the Japanese culture rooted on the Zen philosophy. There are those who specifically attribute the design movement to Japan's spirituality and view of nature.[23]

Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) adopted the motto "Less is more" to describe his aesthetic.[a] His tactic was one of arranging the necessary components of a building to create an impression of extreme simplicity—he enlisted every element and detail to serve multiple visual and functional purposes; for example, designing a floor to also serve as the radiator, or a massive fireplace to also house the bathroom. Designer Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) adopted the engineer's goal of "Doing more with less", but his concerns were oriented toward technology and engineering rather than aesthetics.[24]

Concepts and design elements

[edit]The concept of minimalist architecture is to strip everything down to its essential quality and achieve simplicity.[25] The idea is not completely without ornamentation,[26] but that all parts, details, and joinery are considered as reduced to a stage where no one can remove anything further to improve the design.[27]

The considerations for 'essences' are light, form, detail of material, space, place, and human condition.[28] Minimalist architects not only consider the physical qualities of the building. They consider the spiritual dimension and the invisible, by listening to the figure and paying attention to details, people, space, nature, and materials,[29] believing this reveals the abstract quality of something that is invisible and aids the search for the essence of those invisible qualities—such as natural light, sky, earth, and air. In addition, they "open a dialogue" with the surrounding environment to decide the most essential materials for the construction and create relationships between buildings and sites.[26]

In minimalist architecture, design elements strive to convey the message of simplicity. The basic geometric forms, elements without decoration, simple materials and the repetitions of structures represent a sense of order and essential quality.[30] The movement of natural light in buildings reveals simple and clean spaces.[28] In the late 19th century as the arts and crafts movement became popular in Britain, people valued the attitude of 'truth to materials' with respect to the profound and innate characteristics of materials.[31] Minimalist architects humbly 'listen to figure,' seeking essence and simplicity by rediscovering the valuable qualities in simple and common materials.[29]

Influences from Japanese tradition

[edit]

The idea of simplicity appears in many cultures, especially the Japanese traditional culture of Zen Buddhist philosophy. Japanese manipulate the Zen culture into aesthetic and design elements for their buildings.[33] This idea of architecture has influenced Western society, especially in America since the mid 18th century.[34] Moreover, it inspired the minimalist architecture in the 19th century.[27]

Zen concepts of simplicity transmit the ideas of freedom and essence of living.[27] Simplicity is not only aesthetic value, it has a moral perception that looks into the nature of truth and reveals the inner qualities and essence of materials and objects.[35] For example, the sand garden in Ryōan-ji temple demonstrates the concepts of simplicity and the essentiality from the considered setting of a few stones and a huge empty space.[36]

The Japanese aesthetic principle of Ma refers to empty or open space. It removes all the unnecessary internal walls and opens up the space. The emptiness of spatial arrangement reduces everything down to the most essential quality.[37]

The Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi values the quality of simple and plain objects.[38] It appreciates the absence of unnecessary features, treasures a life in quietness and aims to reveal the innate character of materials.[39] For example, the Japanese floral art of ikebana has the central principle of letting the flower express itself. People cut off the branches, leaves and blossoms from the plants and only retain the essential part of the plant. This conveys the idea of essential quality and innate character in nature.[40]

Minimalist architects and their works

[edit]The Japanese minimalist architect Tadao Ando conveys the Japanese traditional spirit and his own perception of nature in his works. His design concepts are materials, pure geometry and nature. He normally uses concrete or natural wood and basic structural form to achieve austerity and rays of light in space. He also sets up dialogue between the site and nature to create relationship and order with the buildings.[41] Ando's works and the translation of Japanese aesthetic principles are highly influential on Japanese architecture.[23]

Another Japanese minimalist architect, Kazuyo Sejima, works on her own and in conjunction with Ryue Nishizawa, as SANAA, producing iconic Japanese Minimalist buildings. Credited with creating and influencing a particular genre of Japanese Minimalism,[42] Sejimas delicate, intelligent designs may use white color, thin construction sections and transparent elements to create the phenomenal building type often associated with minimalism. Works include New Museum (2010) New York City, Small House (2000) Tokyo, House surrounded By Plum Trees (2003) Tokyo.

In Vitra Conference Pavilion, Weil am Rhein, 1993, the concepts are to bring together the relationships between building, human movement, site and nature. Which as one main point of minimalism ideology that establish dialogue between the building and site. The building uses the simple forms of circle and rectangle to contrast the filled and void space of the interior and nature. In the foyer, there is a large landscape window that looks out to the exterior. This achieves the simple and silence of architecture and enhances the light, wind, time and nature in space.[43]

John Pawson is a British minimalist architect; his design concepts are soul, light, and order. He believes that though reduced clutter and simplification of the interior to a point that gets beyond the idea of essential quality, there is a sense of clarity and richness of simplicity instead of emptiness. The materials in his design reveal the perception toward space, surface, and volume. Moreover, he likes to use natural materials because of their aliveness, sense of depth and quality of an individual. He is also attracted by the important influences from Japanese Zen Philosophy.[44]

Calvin Klein Madison Avenue, New York, 1995–96, is a boutique that conveys Calvin Klein's ideas of fashion. John Pawson's interior design concepts for this project are to create simple, peaceful and orderly spatial arrangements. He used stone floors and white walls to achieve simplicity and harmony for space. He also emphasises reduction and eliminates the visual distortions, such as the air conditioning and lamps, to achieve a sense of purity for the interior.[45]

Alberto Campo Baeza is a Spanish architect and describes his work as essential architecture. He values the concepts of light, idea and space. Light is essential and achieves the relationship between inhabitants and the building. Ideas are to meet the function and context of space, forms, and construction. Space is shaped by the minimal geometric forms to avoid decoration that is not essential.[46]

Literature

[edit]

Literary minimalism is characterized by an economy with words and a focus on surface description. Minimalist writers eschew adverbs and prefer allowing context to dictate meaning. Readers are expected to take an active role in creating the story, to "choose sides" based on oblique hints and innuendo, rather than react to directions from the writer.[47][48]

Austrian architect and theorist Adolf Loos published early writings about minimalism in Ornament and Crime.[49]

The precursors to literary minimalism are famous novelists Stephen Crane and Ernest Hemingway.[50][51][52][53][54]

Some 1940s-era crime fiction of writers such as James M. Cain and Jim Thompson adopted a stripped-down, matter-of-fact prose style to considerable effect; some[who?] classify this prose style as minimalism.

Another strand of literary minimalism arose in response to the metafiction trend of the 1960s and early 1970s (John Barth, Robert Coover, and William H. Gass). These writers were also sparse with prose and kept a psychological distance from their subject matter.[citation needed]

Minimalist writers, or those who are identified with minimalism during certain periods of their writing careers, include the following: Raymond Carver,[55] Ann Beattie,[56] Bret Easton Ellis,[57][58] Charles Bukowski,[59][60] K. J. Stevens,[61] Amy Hempel,[62][63][64] Bobbie Ann Mason,[65][66][67] Tobias Wolff,[68][69][70] Grace Paley,[71][72] Sandra Cisneros,[73] Mary Robison,[74] Frederick Barthelme,[75] Richard Ford, Patrick Holland,[76] Cormac McCarthy,[77][78] David Leavitt and Alicia Erian.[citation needed]

American poets such as William Carlos Williams, early Ezra Pound, Robert Creeley, Robert Grenier, and Aram Saroyan[79] are sometimes identified with their minimalist style.[48] The term "minimalism" is also sometimes associated with the briefest of poetic genres, haiku, which originated in Japan, but has been domesticated in English literature by poets such as Nick Virgilio, Raymond Roseliep, and George Swede.[citation needed]

The Irish writer Samuel Beckett is well known for his minimalist plays and prose, as is the Norwegian writer Jon Fosse.[80]

Dimitris Lyacos's With the People from the Bridge, combining elliptical monologues with a pared-down prose narrative, is a contemporary example of minimalist playwrighting.[81][82]

In his novel The Easy Chain, Evan Dara includes a 60-page section written in the style of musical minimalism, in particular inspired by composer Steve Reich. Intending to represent the psychological state (agitation) of the novel's main character, the section's successive lines of text are built on repetitive and developing phrases.[citation needed]

Music

[edit]The term "minimal music" was derived around 1970 by Michael Nyman from the concept of minimalism, which was earlier applied to the visual arts.[83][84] More precisely, it was in a 1968 review in The Spectator that Nyman first used[85] the term, to describe a ten-minute piano composition by the Danish composer Henning Christiansen, along with several other unnamed pieces played by Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.[86]

However, the roots of minimal music are older. In France, Yves Klein allegedly conceived his Monotone Symphony (formally The Monotone-Silence Symphony) between 1947 or 1949[87] (but premiered only in 1960), a work that consisted of a single 20-minute sustained chord followed by a 20-minute silence.[88][89]

Film and cinema

[edit]In film, minimalism usually is associated with filmmakers such as Robert Bresson, Chantal Akerman, Carl Theodor Dreyer, and Yasujirō Ozu. Their films typically tell a simple story with straightforward camera usage and minimal use of score. Paul Schrader named their kind of cinema: "transcendental cinema".[90] In the present, a commitment to minimalist filmmaking can be seen in film movements such as Dogme 95, mumblecore, and the Romanian New Wave. Abbas Kiarostami,[91] Elia Suleiman,[92] and Kelly Reichardt are also considered minimalist filmmakers.

The Minimalists – Joshua Fields Millburn, Ryan Nicodemus, and Matt D'Avella – directed and produced the film Minimalism: A Documentary,[93] which showcased the idea of minimal living in the modern world.

In other fields

[edit]Cooking

[edit]Breaking from the complex, hearty dishes established as orthodox haute cuisine, nouvelle cuisine was a culinary movement that consciously drew from minimalism and conceptualism. It emphasized more basic flavors, careful presentation, and a less involved preparation process. The movement was mainly in vogue during the 1960s and 1970s, after which it once again gave way to more traditional haute cuisine, retroactively titled cuisine classique. However, the influence of nouvelle cuisine can still be felt through the techniques it introduced.[94]

Fashion

[edit]

The capsule wardrobe is an example of minimalism in fashion. Constructed of only a few staple pieces that do not go out of style, and generally dominated by only one or two colors, capsule wardrobes are meant to be light, flexible and adaptable, and can be paired with seasonal pieces when the situation calls for them.[95] The modern idea of a capsule wardrobe dates back to the 1970s, and is credited to London boutique owner Susie Faux. The concept was further popularized in the next decade by American fashion designer Donna Karan, who designed a seminal collection of capsule workwear pieces in 1985.[96]

Science communication

[edit]

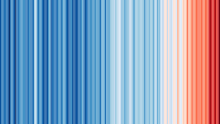

To portray global warming to non-scientists, in 2018 British climate scientist Ed Hawkins developed warming stripes graphics that are deliberately devoid of scientific or technical indicia, for ease of understanding by non-scientists.[98] Hawkins explained that "our visual system will do the interpretation of the stripes without us even thinking about it".[99]

Warming stripe graphics resemble color field paintings in stripping out all distractions, such as actual data, and using only color to convey meaning.[100] Color field pioneer artist Barnett Newman said he was "creating images whose reality is self-evident", an ethos that Hawkins is said to have applied to the problem of climate change and leading one commentator to remark that the graphics are "fit for the Museum of Modern Art or the Getty."[100]

A tempestry—a portmanteau of "temperature" and "tapestry"—is a tapestry using stripes of specific colors of yarn to represent respective temperature ranges.[101] The tapestries visually represent global warming occurring at given locations.[101]

Minimalist lifestyle

[edit]In a lifestyle adopting minimalism, there is an effort to use materials which are most essential and in quantities that do not exceed certain limits imposed by the user themselves. There have been many terms evolved from the concept, like minimalist decors, minimalist skincare, minimalist style, minimalist accessories, etc. All such terms signify the usage of only essential products in that niche into one's life. This can help one to focus on things that are important in one's life. It can reduce waste. It can also save the time of acquiring the excess materials that may be found unnecessary.[102][103]

A minimalist lifestyle helps to enjoy life with simple things that are available without undue efforts to acquire things that may be bought at great expenses.[104] Minimalism can also lead to less clutter in living spaces.[105]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ See Johnson 1947. A similar sentiment was conveyed by industrial designer Dieter Rams' motto, "Less but better."

References

[edit]- ^ "Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties". Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "Universal principles of art: 100 key concepts for understanding, analyzing, and practicing art". Beverly, Massachusetts : Rockport Publishers. 52 (10): 112. 20 May 2015. doi:10.5860/choice.189714. ISSN 0009-4978.

- ^ "Minimalism Movement Overview". The Art Story. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Szalai, Jennifer (21 January 2020). "'The Longing for Less' Gets at the Big Appeal of Minimalism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ Fried, Michael (June 1967). "Art and Objecthood". Artforum. Vol. 5. pp. 12–23. Reprinted: "Art and Objecthood". Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. University of Chicago Press. 1998. pp. 148–172. ISBN 0-226-26318-5.

- ^ Rose, Barbara. "ABC Art", Art in America 53, no. 5 (October–November 1965): 57–69.

- ^ a b c "Minimalism". Britannica. 20 July 1998. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Battcock, Gregory (3 August 1995). Gregory Battcock, Minimal Art: a critical anthology, pp 161–172. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520201477. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ "Minimalism". Britannica. 20 July 1998. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Maureen Mullarkey, Art Critical, Giorgio Morandi". Artcritical.com. October 2004. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ Marzona, Daniel (2004). Daniel Marzona, Uta Grosenick; Minimal art, p.12. Taschen. ISBN 9783822830604. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ Hannah Weitemeier, Yves Klein, 1928–1962: International Klein Blue, Original-Ausgabe (Cologne: Taschen, 1994), 15. ISBN 3-8228-8950-4.

- ^ "Restoring the Immaterial: Study and Treatment of Yves Klein's Blue Monochrome (IKB42)". Modern Paint Uncovered.

- ^ Glaves-Smith & Chilvers 2015, literalists.

- ^ Hogan 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Sfetcu, Nicolae (7 May 2014). The Music Sound. Nicolae Sfetcu. Archived from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ Kamal, Mohammad; Nasir, Osama (2022). "Minimalism in architecture: a basis for resource conservation and sustainable development". Facta universitatis - series: Architecture and Civil Engineering. 20 (3): 277–300. doi:10.2298/fuace221105021k. ISSN 0354-4605.

- ^ Vasilski, Dragana (2016). "On minimalism in architecture - space as experience". Spatium (36): 61–66.

- ^ Cerver 1997, pp. 8–11.

- ^ a b "De Stijl Movement Overview". The Art Story. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ Vasilski, Dragana (2015). "Minimalism in architecture: Abstract conceptualization of architecture". Arhitektura I Urbanizam (40): 16–23. doi:10.5937/a-u0-6858. ISSN 0354-6055.

- ^ Ostwald, Michael; Vaughan, Josephine (2016). The Fractal Dimension of Architecture. Mathematics and the Built Environment. Cham, Switzerland: Birkhäuser; Springer International Publishing. p. 316. ISBN 9783319324241.

- ^ a b Cerver 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Johnson 1947, p. 49.

- ^ Bertoni 2002, p. 10.

- ^ a b Rossell 2005, p. 6

- ^ a b c Pawson 1996, p. 7

- ^ a b Bertoni 2002, pp. 15–16

- ^ a b Bertoni 2002, p. 21

- ^ Pawson 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Saito 2007, pp. 87–88.

- ^ 森神逍遥 『侘び然び幽玄のこころ』桜の花出版、2015年 Morigami Shouyo, "Wabi sabi yugen no kokoro: seiyo tetsugaku o koeru joi ishiki" (Japanese) ISBN 978-4434201424

- ^ Saito 2007, pp. 85–97.

- ^ Lancaster 1953, pp. 217–224.

- ^ Saito 2007, p. 87.

- ^ Pawson 1996, p. 98.

- ^ Bertoni 2002, p. 23.

- ^ Saito 2007, p. 85.

- ^ Pawson 1996, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Saito 2007, p. 86.

- ^ Bertoni 2002, pp. 96–106.

- ^ Puglisi, L. P. (2008), New Directions in Contemporary Architecture, Chichester, John Wiley and Sons.

- ^ Cerver 1997, pp. 18–29.

- ^ Pawson 1996, pp. 10–14.

- ^ Cerver 1997, pp. 170–177.

- ^ Bertoni 2002, p. 182.

- ^ Clark 2014, p. 13.

- ^ a b Greene 2012.

- ^ Loos, Adolf (1913). Ornament and Crime.

- ^ Obendorf 2009, p. 52.

- ^ Davidow, Shelley (2016). Playing with Words A Introduction to Creative Craft. Paul Williams. London: Macmillan Education UK. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-137-53254-1. OCLC 1164505442.

- ^ Meyer, Michael J. (2004). Literature and the Writer. Boston: Brill. p. 213. ISBN 978-94-012-0134-6. OCLC 1239991574.

- ^ "Ernest Hemingway is an example of minimalist writing that indicates flexibility in using relevant phrases shown in his book Research paper for students". Campuscrosswalk. 9 April 2019. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Greaney, Philip John (2006). Less is More: American Short Story Minimalism in Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver and Frederick Barthelme (phd thesis). The Open University. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Wiegand, David (19 December 2009). "Serendipitous stay led writer to Raymond Carver". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Gale, Cengage Learning (2016). A Study Guide for Ann Beattie's ""Janus"". Farmington Hills: Gale, Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4103-5001-5. OCLC 956647072.

- ^ Wagner, Katharina (27 January 2020). Simulacra and Nothingness in Bret Easton Ellis' "Less Than Zero". GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-346-10821-0. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Obispo, Brian Anderson Gil, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis (24 May 2020). "Bret Easton Ellis Remains a Strong Example of a Brave Writer". Study Breaks. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Conway, Mark (26 July 2017). "Bukowski, Charles". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.603. ISBN 978-0-19-020109-8. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Dirty Realism". Poem Analysis. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "K.J. Stevens". The Crooked Steeple. 25 November 2014. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Amy Hempel". www.beloit.edu. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Franklin, Ruth (19 March 2019). "Amy Hempel Is the Master of the Minimalist Short Story". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Mambrol, Nasrullah (23 April 2020). "Analysis of Amy Hempel's Stories". Literary Theory and Criticism. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Shiloh Writing Style". www.shmoop.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Marin, Candela Delgado (1 December 2016). "Bobbie Ann Mason Challenges the Myth of Southernness: Postmodern Identities, Blurring Borders and Literary Labels". Journal of the Short Story in English. Les Cahiers de la nouvelle (67): 223–242. ISSN 0294-0442. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Bobbie Ann Mason: Biography & Writing Style". StudySmarter UK. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Guerrero-Strachan, Santiago Rodríguez (1 January 2012). Realism and Narrators in Tobias Wolff's Short Stories. Brill. ISBN 978-94-012-0839-0. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Literary Minimalism and Tobias Wolff". prezi.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Wolff, Tobias". www.encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ النهار, عبد الاله (1 October 2018). "غريس بالي: کاتبة اختزالية معاصرة". حوليات أداب عين شمس. 46 (أکتوبر – دیسمبر (ج)): 375–384. doi:10.21608/aafu.2018.48113. ISSN 1110-7227. S2CID 204619942. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Grace Paley, Master of Minimalist Writing". A Women's Thing. 21 March 2017. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (2010). Sandra Cisneros's The house on Mango Street (New ed.). New York City, NY, USA: Bloom's Literature. ISBN 978-1604138122. OCLC 401141774. OL 24478421M.

- ^ Jones, Sophie A. (22 May 2020). "Minimalism's Attention Deficit: Distraction, Description, and Mary Robison's Why Did I Ever". American Literary History. 32 (2). England: Oxford University Press: 301–327. doi:10.1093/alh/ajaa004. PMC 7446296. PMID 32863576. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Academic Book: Novels and Short Stories of Frederick Barthelme. A Literary Critical Analysis". mellenpress.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Patrick Holland – The Hong Kong International Literary Festival". Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Bailey, Jeremy R. (December 2010). Mining for meaning: A study of minimalism in American literature (PhD dissertation). Texas Tech University. hdl:2346/ETD-TTU-2010-12-1149. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Greenwood, Willard P. (2009). Reading Cormac McCarthy. Santa Barbara, Ca. ISBN 978-0-313-35665-0. OCLC 615600400.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gabbert, E., "Making the Language Strange, as Only Poetry Can Do", The New York Times, June 21, 2018.

- ^ Davies, Paul. "Samuel Beckett". Literary Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ "From the Ruins of Europe: Lyacos's Debt-Riddled Greece" Archived 10 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine by Joseph Labernik, Tikkun, 21 August 2015

- ^ "The Commonline Journal: Review of Dimitris Lyacos's With the People from the Bridge". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. "The Commonline Journal: Review of Dimitris Lyacos's with the People from the Bridge | Editor Note by Ada Fetters". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2019. [dead link]

- ^ Bernard, Jonathan W. (Winter 1993). "The Minimalist Aesthetic in the Plastic Arts and in Music". Perspectives of New Music. 31 (1): 87. doi:10.2307/833043. JSTOR 833043., citing Dan Warburton as his authority.

- ^ Warburton, Dan. "A Working Terminology for Minimal Music". Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Spectator (6 December 2018). "The Birth of Minimalism". Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023., but note that although this article claims that Nyman's article was "The Origin of Minimalism", that word appears nowhere in the text

- ^ Nyman, Michael (11 October 1968). "Minimal Music". The Spectator. Vol. 221, no. 7320. pp. 518–519 (519).

- ^ "Yves Klein (1928–1962)". documents/biography. Yves Klein Archives & McDourduff. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Gilbert Perlein & Bruno Corà (eds) & al., Yves Klein: Long Live the Immaterial! ("An anthological retrospective", catalog of an exhibition held in 2000), New York: Delano Greenidge, 2000, ISBN 978-0-929445-08-3, p. 226 Archived 28 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine: "This symphony, 40 minutes in length (in fact 20 minutes followed by 20 minutes of silence) is constituted of a single 'sound' stretched out, deprived of its attack and end which creates a sensation of vertigo, whirling the sensibility outside time."

- ^ See also at YvesKleinArchives.org a 1998 sound excerpt of The Monotone Symphony Archived 2008-12-08 at the Wayback Machine (Flash plugin required), its short description Archived 2008-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, and Klein's "Chelsea Hotel Manifesto" Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine (including a summary of the 2-part Symphony).

- ^ Paul Schrader on Revisiting Transcendental Style in Film. 2017 Toronto International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Taste of Cherry". Cinematheque. Cleveland Institute of Art. September 2016. Archived from the original on 14 January 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Gautaman Bhaskaran (23 October 2019). "It Must Be Heaven: Elia Suleiman's sardonic take on the world". Arab News. Archived from the original on 14 January 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ "Films by The Minimalists". The Minimalists. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ Mennel, Stephan. All Manners of Food: eating and taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the present. 2nd ed., (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 163–164.

- ^ Susie, Faux. "Capsule Wardrobe". Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "Donna Karan". voguepedia. Vogue. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Data source: "Met Office Climate Dashboard / Global temperature / Global surface temperatures / (scroll down to) Berkeley Earth". Met Office (U.K.). January 2024. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Raw data has been shifted downward to make use of all shades of blue and red; global warming drove temperatures off the red scale in earlier versions.

- ^ a b Kahn, Brian (17 June 2019). "This Striking Climate Change Visualization Is Now Customizable for Any Place on Earth". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "This Has Got to Be One of The Most Beautiful And Powerful Climate Change Visuals We've Ever Seen". Science Alert. 25 May 2018. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019.

- ^ a b Kahn, Brian (25 May 2018). "This Climate Visualization Belongs in a Damn Museum". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 19 June 2019.

- ^ a b Schwab, Katharine (11 January 2019). "Crafting takes a dark turn in the age of climate crisis". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019.

- ^ Jeon, Hannah (17 June 2020). "A Minimalist Home Can Reduce Stress and Improve Your Well-Being, Experts Say". Good Housekeeping. Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Osborne, Eric (23 August 2023). "A Complete guide on financial minimalism". Financial Guide. Archived from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Town, Phil. "Council Post: Five Ways A Minimalist Lifestyle Can Put Money In Your Pocket". Forbes. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Jeon, Hannah (17 June 2020). "A Minimalist Home Can Reduce Stress and Improve Your Well-Being, Experts Say". Good Housekeeping. Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Bertoni, Franco (2002). Minimalist Architecture, edited by Franco Cantini, translated from the Italian by Lucinda Byatt and from the Spanish by Paul Hammond. Basel, Boston, and Berlin: Birkhäuser. ISBN 3-7643-6642-7.

- Cerver, Francisco Asencio (1997). The Architecture of Minimalism. New York: Arco. ISBN 0-8230-6149-3.

- Clark, Robert C. (2014). American literary minimalism. Tuscaloosa, Alabama. ISBN 978-0-8173-8750-1. OCLC 901275325.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Glaves-Smith, John; Chilvers, Ian (2015). A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-179222-9.

- Greene, Roland; et al., eds. (2012). "Minimalism". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (4th rev. ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15491-6.

- Johnson, Philip (1947). Mies van der Rohe. Museum of Modern Art.

- Hogan, E. (2008). Spiral Jetta: A Road Trip through the Land Art of the American West. Culture Trails: Adventures in Travel. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-34848-3. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- Lancaster, Clay (September 1953). "Japanese Buildings in the United States before 1900: Their Influence upon American Domestic Architecture". The Art Bulletin. 35 (3): 217–224. doi:10.1080/00043079.1953.11408188.

- Obendorf, Hartmut (2009). Minimalism : designing simplicity. Dordrecht [The Netherlands]: Springer. ISBN 978-1-84882-371-6. OCLC 432702821.

- Pawson, John (1996). Minimum. London, England: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-3262-6.

- Rossell, Quim (2005). Minimalist Interiors. New York: Collins Design. ISBN 0-688-17487-6.

- Saito, Yuriko (Winter 2007). "The Moral Dimension of Japanese Aesthetics". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 65 (1): 85–97. doi:10.1111/j.1540-594X.2007.00240.x.

- Shelley, Peter James (2013). Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism (Ph.D thesis). University of Washington. hdl:1773/24092.

Further reading

[edit]- Chayka, Kyle (2020). The Longing for Less: Living with Minimalism. New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781635572100.

- Keenan, David, and Michael Nyman (4 February 2001). "Claim to Frame". Sunday Herald

External links

[edit] Media related to Minimalism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Minimalism at Wikimedia Commons- Agence Photographique de la Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées Archived 30 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "A Short History of Minimalism—Donald Judd, Richard Wollheim, and the origins of what we now describe as minimalist" By Kyle Chayka January 14, 2020 The Nation Archived 19 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine